First Fleeters: Bristol Women transported to Australia

First Fleeters: the Bristol Women

There were only four Bristol women First Fleeters, all adults and all sailed on board the Charlotte. Their lives prior to the voyage are obscure and even thereafter they are seen mostly through the men with whom they were involved. I have tried to cement over these cracks with my imagination. From remarks made by Ralph Clark (Friendship’s Lieutenant of Marines and scribe) it seems they were not among the most troublesome. When the Fleet dropped anchor at Rio on the outward journey, 11 August 1787, he was peeved that ‘six of the very best women’ from Friendship had been exchanged for ‘six of the very worst’ from Charlotte. None were from Bristol.

The conviction of *Ann LYNCH, (c1746?-c1828?) brings to mind Dr Johnson’s infamous gibe ‘under the pretence of keeping a bawdy house, she was a receiver of stolen goods.’ She may have been one of the fairly numerous ‘Bristol Irish’, but Lynch could equally have been her married name. She is thought to have been about forty years old at the time she left England although her precise birthdate is unknown and similarly there is no known formal marriage. She is likely to have been a mother therefore Mary and John Lynch who stood beside her in the dock could have been her children. According to one report, (Bristol Journal, 25.3.1786) the goods which led to Ann’s downfall were valued ‘above the sum of one shilling’. She was sentenced to transportation for 14 years, the harshness of which must mean that she was a habitual ‘fence’. Mary and John were charged with the theft of the same unnamed articles. If they were children this would suggest an ‘Oliver Twist’ situation where youngsters were sent out thieving by an adult. The boy, John Lynch was acquitted but Mary was ‘guilty ‘, sentenced to six months in the Bridewell and to be ‘twice whipped’ at the beginning and end of her term, a cruel sting to concentrate her mind. No comfort or companionship from Ann, her supposed mother, who waited separately in Newgate for the familiar transit, gaol to hulk to transport ship.[1]

Shortly after arrival in New South Wales, Ann began a liaison with a marine, Thomas Cottrell, which led to the birth of a boy also called Thomas, baptised at Port Jackson on 18 October 1788. Lynch and her infant were sent to Norfolk Island on the Sirius in March 1790. By 1794 with her relationship with Cottrell at an end, Ann and her son had moved in with another marine, Thomas Williams, a relationship which became permanent. (A man with good credentials, Williams had been Ralph Clark’s servant aboard Friendship.) Ann was given a conditional pardon in 1800 and in 1805, the family of three left the island, transferring at Port Jackson to the Buffalo bound for Dalrymple. (Thomas Cottrell was on the same ship!) Thomas Williams left the marine corps and as a settler was granted 127 acres in Sydney and began working as a miller. He later became an agent for Simeon Lord, a prominent merchant. By 1822, Ann was officially ‘free by servitude’. In 1825 she was admitted to hospital suffering from an unknown illness. At this time the address of the Williams family was South Head Road, Sydney, which gives an idea of the expansion of the settlement yet sounds so modern and homely that you could address an envelope there and think nothing of it.

The historical Old South Head Road goes through Sydney’s modern shopping centre and passes iconic Bondi Beach. It was originally constructed in 1811 in place of the bridle way which itself replaced the sea crossing to the Signal Station at South Head.

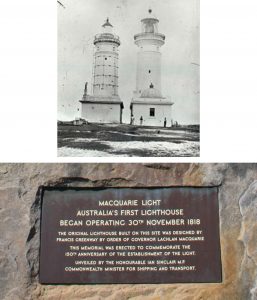

When writing a blogpost you never know who will turn up next. Francis Greenway, a talented artisan of Mangotsfield, Gloucestershire, a village just outside Bristol, pleaded guilty to a white collar crime, and came as a convict to Botany Bay in 1814. It is too much of a stetch to imagine Mrs Ann Lynch Williams would have encountered Greenway, but she definitely would have known his nearby lighthouse, the first to be built in Australia.

The Macquarie Light, old and new, side by side. The original, left, designed by Francis Greenway, convict and architect, began operating in 1818. Photo acknowledgment: Adam.J.W.C.https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=14787592

Ann died sometime between 1825 and the census of November 1828 in which Thomas Williams appears alone. His fate, and that of Ann’s son Thomas is unknown.

Mary CLEAVE or CLEAVER was baptised at Temple Church, Bristol on 12 November 1758, the daughter of John and Susannah. Her parents John Cleave and Susannah Westlake were married at Crediton, Devon in 1754. They had two younger children, John and Susannah baptised at Temple in the name of Cleave and it is likely there was another son James, who would be transported on the Scarborough of the notorious Second Fleet. Mary Cleaver was tried for burglary, convicted at QS on 5 April 1786 and sentenced to seven years transportation. After the customary sojourn in Newgate she was forwarded to the Dunkirk hulk at Portsmouth in wait for Botany Bay. On Dunkirk she found a protector, John Baughan.

Baughan, a cabinetmaker from Oxford, was aged about thirty, a married man with three daughters, aged nine and six year old twins. He was convicted for the theft of five wool blankets worth fifty shillings cut from a rack at New Mill in 1783. The Blanket Weavers of Witney were so outraged they advertised a £20 reward in Jackson’s Oxford Journal for the arrest of the thief. Four hundred handbills were printed and distributed. John was charged due to an unfortunate slip of the tongue by his wife Catherine through which the constable was alerted. John adamantly protested. He had bought the blankets lawfully, he said, for 28 shillings from the (usual, anonymous) ‘man in a pub’. He was prosecuted in the sum of £50 by the Weavers Company, found guilty with the death sentence commuted to seven years ‘to America’. From gaol he was put aboard the Mercury, and thus became one of the mutineers. (see Chapter 1)

His conduct on Dunkirk, no doubt still insisting on his innocence was ‘troublesome at times’. He had spent two miserable years in the hulk before Mary Cleaver arrived to give him solace. She became pregnant in early 1787 just before they went their separate ways in March, John to Friendship and Mary to Charlotte. Her son James was one of three babies born on the ship during the voyage.

John Baughan and Mary Cleaver were re-united in January 1788 on arrival at Sydney Cove, and on 17th February shared the happy event with nine other couples married in one ceremony by the Rev Richard Johnson. Whether the marriage was legal in John’s case is open to question. Tragically, joy was short-lived. Baby James died just over a month after the wedding and was buried on Friday 28th March. Another two infants, Charlotte and Charles followed. Charlotte died at 15 months and Charles buried aged seven weeks on 18 July 1790. There were no further children.

John’s skill as a carpenter and millwright were much in demand. In 1794 he erected a grinding mill in Sydney and was immediately commissioned to build another. According to David Collins, the Judge-Advocate, he was ‘an ingenious man’ despite ‘a sullen and vindictive disposition’. He built a ‘neat’ cottage with an attractive garden for himself and Mary at Dawes Point but in February 1796 became involved in a dispute with several marines who trashed the house. He died in Sydney on 28 September 1797.

Mary immediately started arrangements to leave the Colony; she arrived in Portsmouth in September 1800. It appears that like her fellow Bristolian First Fleeter Aaron Davis, England was not to her liking and by 1802 she was back in Sydney. In the muster of 1806 she was ‘Mary Borne per Charlotte, lives with Richard Harding’ a blacksmith. In 1808 the title of a property at 4 Hunter Street was transferred to her ‘in consideration of love and affection’ by her supposed brother, James Cleaver, who had seemingly made good in Australia from a less than promising start.

Back on 12 July 1787 the Bath Chronicle had reported on James’ career:

‘Monday last arrived in Bristol from Gloucester. Thirteen transports were lodged one night in the gaol and set off at 2 o’clock on Tuesday morning for Portsmouth in order to be embarked on board the ships bound to Botany Bay. Amongst the convicts was the noted Cleavor the famous housebreaker. About eight years ago he broke open a house without Lawford’s Gate of which he was convicted and received sentence of death but was afterwards pardoned on condition of serving on board one of his Majesty’s ships of war. He afterwards enlisted in a marching regiment but soon deserted, came to Bristol and followed his old practice of house-breaking, He having broke open about 42 houses in the parish of St James and parts adjacent he was tried on three different indictments last Assizes in Bristol and acquitted, was then removed to Gloucester and tried for breaking open a house in Thornbury, found guilty and received sentence of death but got his Majesty’s pardon on condition of transportation.’

In July 1819, this time for good, Mary and Richard Harding sailed for England aboard the Surry, (sic) and out of history. In October the same year brother James was living at Parramatta west of Sydney when he and his wife, another Mary Cleaver, witnessed the marriage of two ‘prisoners’ John Herbert and Ann Dudley. In 1828 John Roley, the district constable of Prospect (a Sydney suburb) listed 38 residents of whom ‘Mary Cleaver, tenant, (is) Free by servitude. This woman permits drinking in her house and is a general harbinger (sic) of Bushrangers.’[2] She must be James’ wife or widow.

*HANNAH JACKSON who was born about 1757 was found guilty on 28 July 1785 at Bristol, and sentenced to seven years transportation for stealing three yards of lawn, a cotton fabric used for making dresses. She remained in Newgate until forwarded to the Dunkirk hulk on 10 December 1785. She was removed to Charlotte in March 1787 and departed in May with the First Fleet. She was among those sent to Norfolk Island in 1790 on the Sirius and there met Joseph Dunnage, a veteran of the ‘Swift mutiny’, (see Chapter 1) Dunnage had been widowed in 1788 when his bride Sarah Parry, weakened by the voyage, died only a month after their wedding. On 3 October 1791 on Norfolk Island Ralph Clark reported in his usual matter of fact manner that ‘Dullage’ was

‘Punishd with fifty lashes for repeated Disobedience of Orders and neglect of Duty’.

Dunnage and Hannah returned to the mainland in 1793 and the following year Joseph was awarded 30 acres at Mulgrave Place. By 1800 he and Hannah were living together. They may have gained experience of agriculture whilst on Norfolk and at first things seemed to go well with two acres of wheat sown and another five made ready for maize. By 1802 eleven acres were cleared, whereupon there was a setback. It is possible that alcohol played its part and by 1806 Joseph had lost his farm and was subsisting on rented land, working in partnership with another man.

Matters continued to slide and in 1811 he was charged with distilling illegal spirits. He was sent to the Penal Settlement at Newcastle on 2 November 1813 via the Estramina.

Newcastle, formerly called Coal River was established in 1801 as the colony’s first place of secondary punishment. The unlucky inmates who called it ‘the Hell of New South Wales’ endured a miserable existence: back breaking work ten hours a day in the coalmines, logging, shingle splitting for roof tiles, or lime making on the shore, scanty rations and inadequate clothing. They suffered ‘dysentery in summer, the bitter cold in winter and chest complaints all year round.’ They lived under military discipline supervised by ‘trusty’ overseers where ‘King Lash’ ruled. Corporal punishment, for misdemeanours, as set by government decree, was meted out dutifully by successive Commandants, though some were more humane than others.

Governor MacQuarie who made an official visit in 1812, ’viewed the coalmines and the parts of the river where lime is made’ and pronounced his pleasure that the ‘useful settlement’ currently provided Sydney with Cedar, Coals and Lime; that higher up the river the soil was fertile and in time would support agriculture fit for the increasing population of the country. The convicts welcomed his award of a day’s holiday. Generally the only diversions were provided by ‘the many shipwrecks’ around the coast. (‘Wrecking’, passive, taking valuables from a ship which had foundered close to the shore was the mainstay of many a marginalized coastal community.)

The most dreaded punishment was kept for persistent offenders, who were sent to Hunter Valley, to dig oyster shells for lime burning. The smoke from the kilns affected the eyes and in worst cases caused blindness. Even so it was alleged that some prisoners deliberately exposed themselves in the hope bad eyesight would excuse them from the work. The boats which took the lime to Sydney were moored off-shore in water too shallow to allow docking nearer to land. The convicts waded out to the boats hefting sacks or baskets of lime on their backs, wet through at the mercy of the waves. Apart from the sheer drudgery they were easily burned by the lime, being without any form of protective clothing, often no more than a ragged shirt tied round the middle. At the end of each exhausting day they retired to huts where beds or blankets were non-existent. The men gathered seaweed from the shore and laid it inches deep on the ground, some bunking in together and dragging it over themselves ‘in short burying themselves in a dunghill to keep warm’.

The system ceased about 1822 when the source, the oyster shells, once so plentiful ran out.

Joe Dunnage was a prisoner until at least 1817, by which time he was over sixty. Following his release he worked as a labourer at Windsor. He and Hannah, who had survived alone during his absence, were reunited as man and wife, and both over 70, were counted in musters at Richmond, 1822 to 1828. No further records have been found for the couple.

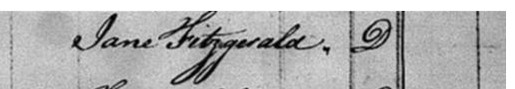

JANE FITZGERALD, c1757-1806, from her surname may have been another woman of Irish extraction. Nothing is known of her life until she was tried on 4 April 1786 for an un-named felony and sentenced to seven years transportation. At Sydney Cove in 1788 Jane began a whirlwind affair with a marine, Private William Mitchell, an Irishman from Bandon, County Cork, who had arrived with the Lady Penrhyn. Their sons, William and James, arrived on 9 October 1788, the first set of twins born in the colony. Sadly, baby James died aged three months and was buried on 15 January 1789 as James Mitchell Fitzgerald. Jane and her surviving son left for Norfolk Island, disembarking at Cascade on 14 March 1790.

William Mitchell came to the island in April 1791 on the Supply but left almost immediately for Sydney where he obtained his discharge from the Marines. He returned to Norfolk as a settler in November 1791.

Jane and William’s disjointed relationship does not seem particularly happy, for William departed again for the mainland in March 1793, aboard the Kitty, taking with him his son, William junior, now five years old. Men of course had paramount rights over their offspring, but this seems unbearably callous and cruel.

In Sydney William senior enlisted again. William junior joined the New South Wales Corps as a drummer on 25 June 1800 at the age of eleven.

Jane journeyed to and from Norfolk, probably to find her ‘husband’ and son, leaving the island in May 1795, returning in 1796, empty handed, and departed again in 1801. In 1806 in Sydney she is described as being self-employed with no children, in ‘a concubinage relationship’.[3] It is not known whether she saw her son before she died. She was buried at the Old Sydney burial ground on 2 September 1806.

The Mitchells, father and son returned to England in May 1810 when the NSW Corps was recalled.

Elizabeth Lock appears next to Ann Lynch on the Norfolk Roll and though she was not convicted in Bristol, she is connected through her marriage to Richard Morgan, of St Philip & St Jacob, (one of the men in 4a). Liz Lock is notable – at least in my experience – for a unique request. She asked to be transported to Botany Bay!

She was born about 1763 and tried at Gloucester for two counts of breaking and entering, stealing a black silk hat, a black ribbon, a scarlet cloak and a linen cap. (The young men were not the only one with a fancy for nice clothes.) She was condemned to death for her crimes, and ‘pardoned’ on condition of ‘transportation beyond the seas’. She was still confined in Gloucester Gaol two years later when she met Richard Morgan. They were romantically linked between his conviction in the spring of 1785 and his transfer three months later to the Ceres hulk on the Thames.

Gossip about the proposed sailing to Botany Bay was common knowledge among all the prisoners. Petty and habitual crooks alike, even the most’ hardened’ were known to utter that they would rather be hanged and have done with it. Liz would have nine of it.

Perhaps in remembrance of their fond embraces, she put in an application to go into the unknown with the First Fleet. She appealed that ‘her character was lost’ and she would be more likely to adhere to the Commandment ‘Thou shalt not steal’ in a new country where she would be on a par with others in the same situation. This may have struck home with a zealot eager to prove the merit of the project, especially if it meant saving a lost soul from the clutches of Satan. So Elizabeth got her way, and was ‘conveyed to London’ in December 1786 by Mr. Giles, the keeper of Gloucester Gaol. If she hoped to be sent to the Ceres at Woolwich and a blissful reunion with her lover, she was disappointed. The Ceres was for men only. Liz was confined in the Bridewell with other women and children, picking oakum, arduous and tedious work separating bits of old tarred rope, needed to caulk gaps in the wooden ships. For ten or twelve hours a day. Definitely no picnic.

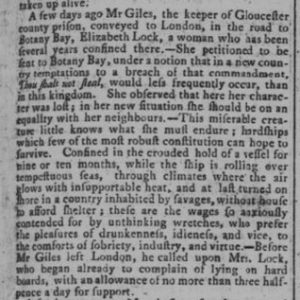

The Leeds Intelligencer issued a dire warning that worse was yet to come:

Leeds Intelligencer, 26 Dec 1786

This miserable creature, it thundered, little knows what she must endure; hardships which few of the most robust constitutions can hope to survive, confined in the crouded (sic) hold of a vessel for nine or ten months whilst the ship is rolling over tempestuous seas through climates where the air glows in insupportable heat, and at last turned on shore in a country inhabited by savages with house to afford shelter; these are the wages so anxiously contended for by unthinking wretches who prefer the pleasures of idlenes, drunkenness and vice to the comforts of sobrity, industry and virtue.

Mr Giles called to see the prisoner in her new quarters before he went home. With some hint of ‘I told you so,’ he reported that she was already complaining of lying on hard boards with only three halfpence a day for support.

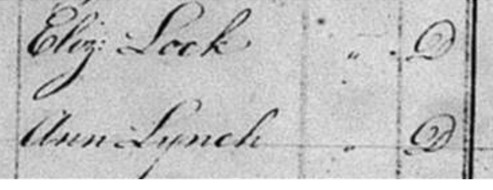

Eliz: Lock & Ann Lynch listed beside each other on the Norfolk Island Roll

She had to wait six months before she sailed with the First Fleet (Lady Penrhyn) in 1787. Richard was on the Alexander. They were married in Sydney on 30 March 1788, three months after meeting again.

Sadly the (presumed) rapture did not last. The marriage may have already faltered by the time the couple arrived separately on Norfolk Island, Richard on Supply in January 1790 and Liz on Sirius two months later on 5th March. She disembarked on the 14th at Cascade before the wreck. By November, a marine of the 38th Company, Thomas Scully had arrived on the island as a settler and in April 1791 he was awarded a 60 acre grant of land at Bumbora Road. He and Elizabeth began a relationship and are recorded together in 1794. A year later Scully was selling off pieces of his plot to various others in preparation for leaving. One of the buyers was William Blatherhorn, the old mutineer, who had recently been recommended for a conditional pardon on the grounds that he had been a reliable overseer. A few years later he was made constable. Another ‘bad boy made good’.

Mr and Mrs Scully left Norfolk Island in 1795 aboard the Asia, an East Indiaman, for India and homeward bound.

The Asia by William John Huggins (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

[1] Bath Journal 30.3.1786 states Ann’s ‘assistant’ as ‘Ann Obery’ with no mention of Mary & John.

[2] Paula J Byrne, ‘Criminal Law & Colonial Subjects’, 2003

[3] Gillen, Mollie. ‘The Founders of Australia’. This may be where Jane’s alias ‘Phillips’ came from

To avoid an excess of footnotes information may be found on the following:

https://peopleaustralia.anu.edu.au/biography/fitzgerald-jane-31019

https://www.freesettlerorfelon.com/searchaction.php

https://peopleaustralia.anu.edu.au/biography/dunnage-joseph-30792

https://www.freesettlerorfelon.com/lime_burning.htm

https://hmssirius.com.au/elizabeth-lock-convict-lady-penrhyn-1788 https://hmssirius.com.au/thomas-williams-private-marines-33rd-plymouth-company-friendship-1788-and-ann-lynch

https://hmssirius.com.au/elizabeth-lock-convict-lady-penrhyn-1788-and-thomas-scully by Cathy Dunn.

With thanks to the blog ‘Thornbury Roots’ which led me to James Cleaver.