First Fleeters – Bristol Men transported to Australia

For an introduction read Wanton Wenches’ and ‘Incorrigible Rogues’ Chapter 3: The Bristol First Fleeters

NB: to avoid repetition ‘Quarter Sessions’ is abbreviated to QS. ‘Newgate’ is the Bristol gaol, not to be confused with London’s prison of the same name.

* Those marked with an asterisk went to Norfolk Island 1790 and survived the wreck of the Sirius.

BARRY, John, c1768-1788, Friendship & *KIDNER, Thomas, alias Kidney, 1767-? Alexander.

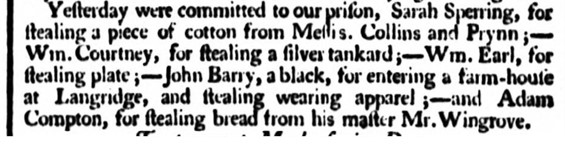

These two young men knew each other at least from 19 September 1782 when a report appears in the Bath Chronicle:

‘Thursday were committed to Newgate, John Barry, Wm. Northcutt and Tho. Kidney [sic] for stealing 4 pieces of Irish linen, value £6, the property of Mr. William Overend, and Elizabeth Pollard for receiving one piece of Irish linen knowing it to have been stolen.’

(The merchants, William Overend & Co, were active in Bristol’s infamous ‘Africa Trade’.)

Kidner, judged to be the ringleader of the group, was sentenced to transportation for seven years ‘beyond the seas’ while the others, convicted of ‘inferior offences’ received ‘lesser terms of imprisonment and to be publicly whipped.’

Thomas Kidner was baptised at South Petherton, Somerset on 16 November 1765, the son of James, a farm labourer, and Mary.

Following his court appearance, young Tom, who was still only 16 when convicted was taken to Newgate where he spent four years until transferred to the Censor hulk at Woolwich. On 6 January 1787 he was removed to Alexander, sailed with the First Fleet in May 1787 and arrived in January 1788.

Conditions in the colony were harsh, punishments brutal. In 1789 he was sentenced to 150 lashes for ‘obtaining necessaries’ from a marine, Mark Hurst. (The next year, when the colony had even less food, the same Hurst was charged with the theft of rice from the communal store. He was sentenced to 500 lashes. He survived and returned to England on the Gorgon in 1791.)

In 1790, Kidner was sent from Botany Bay to the alternative settlement, the remote Norfolk Island, a dot in the ocean, about a thousand miles from Sydney. He lived there for 15 years, during which time he married Jane Whiting, who, aged 14, had been transported on the female ship, the notorious Lady Julian. They had two children. By 1807 they were resettled in Tasmania though they later separated. The date of Thomas’ death is not known but Jane died in Hobart in 1826 at the age of fifty.

In 1790, Kidner was sent from Botany Bay to the alternative settlement, the remote Norfolk Island, a dot in the ocean, about a thousand miles from Sydney. He lived there for 15 years, during which time he married Jane Whiting, who, aged 14, had been transported on the female ship, the notorious Lady Julian. They had two children. By 1807 they were resettled in Tasmania though they later separated. The date of Thomas’ death is not known but Jane died in Hobart in 1826 at the age of fifty.

Almost two years passed before John Barry next appears in the news, in the Bath Chronicle, 19 August 1784:

John was one of a small black population who lived in Bristol and Bath in this era. A scant reference in the same newspaper, 31 March 1785, not mentioning his colour, states that he and others were tried for ‘sundry thefts’. By the end of the year he was in trouble again, and on 23 November 1785 at Bristol QS he was sentenced to transportation for seven years.

On 11 March 1787 he went aboard Friendship, one of the miniscule number of black convicts on the First Fleet; he is listed by Ralph Clark as ‘Jno Barns’, aged 19, no trade, convicted for the theft of three pairs of stockings.’

He died on 10 March 1788 shortly after arriving at Sydney Cove.

BRICE, William, c1771 – ? Friendship. For years outraged citizens of Bristol had been complaining about the number of seemingly feral boys who lived on the streets, causing nuisance and mayhem; nobody as yet thought these destitute children might be in need of care and protection. (Orphanages, Training Ships and the removal of poor youngsters ‘for a better life in Canada’ would come with the Victorians.) William was only fourteen when sentenced to seven years on 11 February 1785 for taking a looking glass, from a shop in St Peter Street. (Size unspecified; if this was a small hand glass, the theft was pitiful; if large an encumbrance.) Unfortunately his sentence of seven years was a formality: he had been whipped for a previous offence in 1784.[1] He had already been locked up for two years when he arrived aboard Friendship. His birthplace can only be guessed at, but it is worth noting that a William Brice, ‘father unknown’, the son of a single woman, Mary Nowell, was baptised at North Petherton on 7 July 1770, a stone’s throw from the village Thomas Kidner called home. If he is the same, then this young Billy Brice would fit the general pattern of the unwanted urchins, especially if orphaned. Aboard the Dunkirk hulk his behaviour was ‘tolerably decent and orderly’.

Brice survived the ordeal of the voyage, and is named in victualling lists for 1788. In 1789 he was called as a witness when one convict accused another of making threats against him. He then disappears from the records. Various alternatives have been suggested: he ‘left the colony in 1792 when his sentence expired’; he ‘found a ship and worked his passage home’, or ‘he was lost in the bush’.

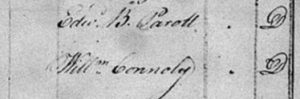

*CONNELLY, William, c1760 –? & *PERROTT, Edward Bearcroft, c1760-? transported by Alexander, they were jointly charged with the theft of clothes from the Swan Alehouse in Temple Street. They were found guilty on 3 February 1785 at the Bristol QS and sentenced to 7 years. They were sent to the Ceres hulk, where they remained until they embarked with Alexander, arriving in Sydney in January 1788.

William Connelly married fellow First Fleeter, Elizabeth Thomas, (Prince of Wales) at Sydney Cove on 19 October 1788; their son William, who was baptised on 5 July 1789, lived for only three months.

Connelly and his wife were sent to Norfolk Island on the Sirius in March 1790 and survived the shipwreck. By March 1791 they were living on a one acre lot at ‘Sydney Town’ on the island and by the end of the year Connelly was a member of the night watch. In May 1792 he was selling surplus grain and meat to the Government stores.

Leaving his pregnant wife behind, he boarded the Sugar Cane, for India in October 1795, presumably to work his passage. This three-decker merchantman, having recently landed Irish convicts in Botany Bay obtained a contract from the East India Company in Calcutta and returned to London via Madras, St Helena and Kinsale. She later became a slave ship.

It is unknown whether Connelly stayed with the ship all the way home. Elizabeth Connelly who remained in Australia found another man, James Waterson with whom she was living in 1796.

Edward Bearcroft Perrott, alias Parkins, likewise arrived at Cascade, Norfolk Island, in March 1790 and lived there with Ann Read who was serving life ‘for assault and theft on the King’s Highway’. On 30 September 1791, a convict called Thomas Seal absconded and was absent from work until 10 o’clock on the night of 10th October when he was caught scavenging in Perrott’s garden. Seal, weak from ten days in the bush, was flogged with 49 lashes: when, as it is quaintly put in other cases, he could probably ‘bear no more’.

‘Mates’. Perrott and Connelly were still side by side on the Norfolk Roll.

With his time served, Perrott left the settlement in January 1793 aboard the Philadelphia, bound for China.

*DAVIS, Aaron, c1761-c1813, & CROWDER, Thomas Restell or Risdale, c1758-1824, both Alexander, were jointly charged and found guilty on 29 March 1785 at Bristol QS for stealing watches and rings from a John Gunning.

Davis, whose case was immediately proved, spent a few months in Newgate before being transferred to the Ceres hulk where he remained until taken to Alexander for transportation. He arrived in New South Wales in January 1788. Perhaps originally a baker, he was making bread for the Sirius before leaving for Norfolk Island in 1790. Described ‘very industrious’, he cleared 24 rods of a one-acre site where he supported two females, Mary Walker, the mother of three of his children, and a four year girl, Sarah Lee. His bakery prospered and he began a modest business. In 1804, his son Francis, by Elizabeth Hosier was born. With his time served by 1805, he left his enterprise in the hands of James Mitchell, by then the husband of Sarah Lee. It is not known whether Aaron ever returned to Bristol, but England, wherever he was, did not live up to his expectations. He suffered financial losses and was disillusioned by 1813 when he issued a petition to return to New South Wales with his two daughters. Unfortunately, he died before his case could be finalised.

Aaron Davis’ encounter with Thomas Restell Crowder was apparently fleeting – they did not know each other at all, (he said), though he had seen Crowder in the same auction room before they were arrested.

Crowder was a Londoner, born at St Martin-in-the Fields, a career criminal with ‘previous’. An unsuccessful burglar, his conviction, aged 25, in 1783 at the Old Bailey under the heading, ‘Newgate, London’ was for intent to steal from John Bradford at St Mary-le-bone:[1]

He received the mandatory ‘death recorded’, commuted to transportation. The British Government, in cloud cuckoo land, expected ‘normal service would be resumed’ after losing the war, and in due course, Crowder was taken from his prison to the Mercury, bound ‘for America’. Thus in 1785, he became one of the ‘Mercury Mutineers’. (see Chapt. 1) He evaded capture and escaped to Bristol where allegedly he fell in with a local lad, Aaron Davis, and was charged with ‘thefts of a very large amount’. Aaron, the lesser party, was immediately sentenced to transportation, but judgement on Crowder was deferred; he was indicted for another burglary as well as the mutiny. When these cases were heard, he was sentenced to death twice, and was in the condemned cell awaiting the ultimate turn off when the Recorder became uneasy about evidence given by an informer. Crowder was reprieved on both counts. By now, having escaped the hangman three times, his sentence was commuted to transportation for life, again ‘to America’. This, of course, did not happen. He was put on board the Justitia hulk and on 6 January 1787 was delivered to the Alexander in readiness for Botany Bay.

He and his wife Sarah Davis were sent to Norfolk Island on the Supply in February 1789 where he became an overseer and was recommended for good behaviour by Lieutenant Governor Philip Gidley King. He was emancipated in 1782 and became a settler. In January 1794 he became involved in a fracas with a sergeant and was sent to Sydney in irons. He returned to the island shortly afterwards which suggests he was exonerated. After the death of his wife he lived quietly cultivating his land and in 1809 went to Tasmania (then Van Diemen’s Land) with other islanders. In 1813 he became Superintendent of Convicts with a salary of £50 per annum. On retirement he was superannuated for services rendered. He died in Hobart on 28 November 1824, ‘a much respected former government employee’.

His obituary appears in the Hobart Town Gazette, 3 December 1824:

‘DIED. On Sunday last, in his 67th year, at his residence in Elizabeth-street, Mr. Thomas Restell Crowder, 36 years an inhabitant of these Colonies, and several years Principal Superintendent of Convicts, much lamented and regretted by his friends.’

The full history of Crowder’s life in Australia is admirably documented online by John Boyd of the ‘Fellowship of the First Fleeters.’

DENNISON, Barnaby, c.1758–1811, Alexander, was found guilty on 30 April 1783 at Bristol for stopping Richard Jones in Castle Precincts with ‘intent to rob’. Sentenced to 7 years transportation he was taken to the Censor hulk, until he embarked on the Alexander in 1787.

After arrival in the colony he was charged, with a seaman, Walter Ellis, and seven others for rowdiness, ‘making a noise at an improper hour and disputing the authority of the Guard’, Sergeant (Richard) Clinch, and his escort, the second part of the offence being far more serious. Ellis was sentenced to 100 lashes, Dennison to 50. The rest escaped with reprimands.

In February 1800, evidently reformed, he was sworn in as a constable at the Dawes Point district and by 1806 was working as a stone mason. He received a 30 acre grant of land at Toongabbee in Sydney.

Barnaby Dennison died at Sydney General Hospital and was buried on 28 April 1811, his age given as 58. Clinch died in a drowning accident in 1799.

*ELLIOT, Joseph, alias Trimby, c1767-1836, Friendship, a son of Richard Elliot and Christian Trimby (married Horningsham, Wiltshire in 1755). Aged 17 he was sentenced to seven years transportation at Bristol QS on 24 November 1784 for the theft of a tobacco pouch. His early life prior to removal to the hulk has been told in Chapter 2, ‘The Inhabitants of Newgate’. He is listed by Ralph Clark, 1787, as ‘aged 20, a gardener, theft of a pocket book’. Clark mentions him again in the Journal entry, 18 December 1790, as ‘one of the carpenters’ on Norfolk Island, 18 December 1790, for

‘shirking his work three different times [……] and would not be Quite [sic] when I orderd him.’

He was brought to Town where Major Ross sentenced him to 100 lashes, but he could only bear 73. He was then ordered him back out to Charlotte Field where Clark was in command.

On Norfolk, Joseph Elliot married Elizabeth Sieney, a former acquaintance from Bristol who was part of a loose network of young people who were in and out of Newgate. Elizabeth, transported on Lady Julian, was the sister of James, a fatality of the wicked Second Fleet.

The full horror of Joseph’s life in Australia, almost the exact opposite to that of Thomas Crowder can be found online in a biography, ‘Trimby’s Travels’, by Sister Andrea Myers of the Fellowship of the First Fleeters. She tells how that first 7 year conviction stretched to 47 years of imprisonment and barbaric punishment, 1784-1831. Myers says: ‘…….all because of an empty pouch. Joseph served his time in every way.’

Farley, William, see Neal[e], James

*FINICY, Thomas, alias Fillesey, Tillesey, Finnesy, 1758 – c1795? Alexander, was indicted as Tillesey but in the colony was more often recorded as Finicy. He was found guilty at Bristol on 29 April 1783 for the theft of a pair of shoes with buckles and sentenced to 7 years transportation. After about a year in Newgate, he was sent to the Dunkirk hulk and remained there until discharged to Alexander to await transportation. He arrived in Sydney in January 1788.

From the start of 1789 he was continually in trouble. On 9th February at Port Jackson he received 50 lashes for being absent from work for three days; on 3rd October he was reprimanded for stealing a pair of shoes belonging to Richard Partridge, which he said was just a prank. John Coen Walsh, a member of the Night Watch spoke up for him, saying he had never known Finicy to steal. The matter was written off but it marked him out and on 7th November his penalty was 100 lashes ‘in the usual manner’ for attempting to break open a box belonging to George Fry. On 16 February 1790 he was given another twenty five for neglect of work. In March he departed on the Sirius for Norfolk Island. Sirius was shipwrecked in the harbour and though there was no loss of life, the ship and much of the stores were lost.

On the 15th May ‘Finnesy’ stole a cabbage from Lieut. Creswell’s garden, and was on the run for twelve days. He was punished by having his weekly flour ration reduced from three to two pounds for ten weeks and to work in irons for that time.

By 1 July 1791 he was subsisting on a Queenborough lot with 66 rods cleared and sharing a sow with William Davis and Jane Read.

He left Norfolk Island on the Atlantic in September 1792 and was in Port Jackson until 24th October when he was marked ‘off stores’. He was either dead or managed to work his passage home. In any event he is never heard of again.

*GUNTER, William, alias Gunther, c1764- ? Alexander, tried at Bristol, 4 August 1783, was sentenced to 7 years transportation for ‘felony’. He spent over two years in Newgate before he was taken to the Dunkirk hulk in late 1785 where his behaviour was ‘tolerably decent and orderly’. He sailed with the Alexander and arrived in January 1788. He was sent to Norfolk Island in March 1790 aboard Sirius.

On 20 August 1791, Ralph Clark records

‘Punish’d Isaac Williams with 100 Lashes and William Gunter with 59 Lashes – Gunter was also orderd to receive 100, but could not Bear more than the 59 – they both were punishd for Neglect of Duty.’

And on 17 October 1791:

‘I punished Wm. Gunter with 50 Lashes at Phillipburgh for quitting the duty he was orderd on and going into the Woods and Staying there a week. This said Gunter is a very bad Subject.’

Gunter was working as a labourer for William Fisher in May 1794 and with his sentence completed, he left the colony, and is presumed to have signed on as a seaman aboard HMS Daedalus, which was returning home from a three year voyage to the South Seas.

HOLLISTER, Job, c1766 -? Alexander, was indicted for the theft of tobacco from a shop in Castle Street, Bristol on 31 December 1784. He appeared at the QS in February and was sentenced to seven years transportation. The Gaol Delivery Fiat 30 April 1785 states that three others received the same sentence, John Wisehammer, James Neale and William Farley. He was aboard the Ceres hulk by 7 January 1786 and then discharged to Alexander in January 1787 in preparation for the voyage. He arrived in Australia in January 1788.

He kept his head down in the Colony and is only mentioned once, ‘off stores’ by July 1793, when he is believed to have signed aboard HMS Daedalus with William Gunter..

Jones, Thomas, see Leary. Jeremiah

Kidner, Thomas, see Barry, John

LAMBETH, (Lambert) John, 1763-88, Friendship, a blacksmith, born in Warwickshire, believed to be the son of John & Catherine Lambert baptized at Fillongley, 7 April 1763. He was convicted at Bristol on 29 March 1785 for the ambitious theft of ‘£3.7s and a £5 promissory note’ though Ralph Clark in 1787 states the sum to be £1.19s. His conduct aboard the Dunkirk hulk was ‘tolerably decent and orderly’. He survived the voyage but died a few months after arriving in the colony. He was buried at Sydney Cove on 2 July 1788 as John Lambert.

*LEARY, Jeremiah c1765-c1807, & *JONES, Thomas, c1765-c1805, Friendship, were convicted of ‘housebreaking’, which amounted to the theft of a pair of gloves from a Mr. Benjamin Montague, on 30 March 1784. A mandatory ‘death recorded’ sentence, was commuted to 14 years transportation for each man. The severity of the term suggests they had previous ‘form’.

Leary, possibly Irish by his surname, and Jones spent a few months in Newgate followed by the Dunkirk hulk on 18 August 1785 where they remained until February 1787 when they were delivered to the Friendship. Leary (spelt ‘Learly’ by Ralph Clark) was then aged 22. He arrived at Sydney Cove in January 1788 and was sent to Norfolk Island on the Sirius in March 1790. Soon afterwards, he was forced to ‘run the gauntlet’ by fellow convicts for theft, a bloody punishment, recorded as ‘severe’. He subsisted on the island until 1807 when he was marked in returns as ‘dead’.

Thomas Jones, a bricklayer from Warwickshire, also 22, as recorded by Clark, likewise went to Norfolk Island, where he disembarked at Cascade, 14 March 1790. He ‘received rations’ until 1795 with no other information until he was ‘off stores; sentence expired’ in February 1805. By 7th June that year he was dead, recorded by Rev Fulton as ‘Jones, freeman’.

*MARTIN, Stephen, c1746/8 -1829, Alexander, was sentenced on 30 April 1783 at Bristol QS to seven years transportation. Various transcribers have read his crime as ‘the theft of a cann (sic) and a pair of boots and spurs’, which as a combination made no sense. Then only recently I discovered the truth in Stephen’s fine online biography by Kathleen Rutherford.

*MARTIN, Stephen, c1746/8 -1829, Alexander, was sentenced on 30 April 1783 at Bristol QS to seven years transportation. Various transcribers have read his crime as ‘the theft of a cann (sic) and a pair of boots and spurs’, which as a combination made no sense. Then only recently I discovered the truth in Stephen’s fine online biography by Kathleen Rutherford.

(It was a cane, of course, not a can. So Stephen was immediately transformed into an aspiring dandy, dashing in his boots, spurs, and walking cane. All he needed was an outfit to match, perhaps Thomas Finicy for the buckles, Peter Morris, the breeches and waistcoat, John Barry for the hose and Jeremiah Leary, the gloves!)

The Coach and Horses still currently in operation, 2022, is about 10 miles from Reading on the Bath Road to London.

Stephen’s Bristol story began three years before when he and his brother William arrived in the city from Cornwall to try their luck. They had been working a mere week as porters for William James when they were accused by the son of the house, John Sartain James, of taking two chests of tea, valued at £60 from a Jacob Street warehouse and giving instructions for it to be delivered to an inn, the Coach & Horses at Meacham, near Newbury, Berkshire. This seems to have been a significant theft of a fashionable commodity, which makes the lenience of their sentence, one year apiece in Newgate and fined a shilling, all the more suspect. Many people had been hanged for less.

So why did they get off so lightly? It is implied that Mr. James was a merchant, though his obituary in a Bath newspaper tells a different story. He was

‘many years carrier from this city, London and Exeter which he had some time since declined in favour of his son, John Sartain James.’[1]

The Coach and Horses is about 10 miles from Reading on the Bath Road to London. Instructions must have been given for delivery to the address, a pub probably a frequent port of call on the James’ route. Somebody was clearly up to something but the Magistrates could not quite decide what, so the Martins took the fall: ‘Give ‘em a year each to be on the safe side.’ For William it was particularly disastrous. He caught smallpox in Newgate and died.

The boots and spurs for which Stephen was convicted in 1783 were valued at ten shillings, and belonged to Henry Payne of the Queen’s Head. Elizabeth Yandell of another pub, the Plough in West Street, also chipped in saying he had stolen a cane from her which she valued at 40 shillings. This was either a spectacular piece or more likely she said the first sum which popped into her head.

So then Stephen was on his way back to Newgate and a couple of years later to the Censor hulk on the Thames. On 6 January 1787 he was transferred to the Alexander.

Once in the colony he received the obligatory flogging, 25 lashes, for neglect of work, in February 1789 and a more severe 50 in November for theft. He was sent to Norfolk Island in 1790, where the next year he married Hannah Pealing in a mass wedding involving ten couples. He received a grant of land and became relatively prosperous: he had an employee and sold surplus grain to the government. By 1805 his little house was valued at £15. He was widowed when he left Norfolk in 1808, with his daughter, his only child, when the islanders were re-settled in Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania).

Stephen died in Tasmania aged 81 in 1829.

*MORGAN, Richard, c1761-1837, Alexander, is believed to have been born at St Philip and St Jacob, a large parish east of Bristol the majority of which was then in the county of Gloucestershire, hence Richard being tried 40 miles away in the county town. On 23 March 1785 he was convicted of stealing a watch and demanding a promissory note with menaces from an un-named man. He was sentenced to transportation for seven years and transferred to the Ceres hulk on the Thames in June the same year. He embarked for New South Wales on the Alexander in January 1787.

In Australia he became re-acquainted with Elizabeth Lock, (of the Lady Penrhyn), who he had met when both were in Gloucester Gaol. The couple were married in Sydney on 30 March 1788, two months after their arrival.

Sadly, the romance did not last. They were sent to Norfolk Island in 1790 on different ships, Dick on Supply, Liz on Sirius. On arrival they went their separate ways.[2]

The later history of Richard Morgan, his second wife Catherine Clark, and their seven children is told in detail online by Cheryl Timbury; Richard is also ‘the hero’ of a novel, ‘Morgan’s Run’ by Colleen McCullough.

He was buried on 26 September 1837 at Clarence Plains, Tasmania, his age given as 78.

MORRIS, Peter, c1759-? Alexander, was found guilty on 12 July 1784 at Bristol for the theft of breeches and a waistcoat. He was sentenced to 7 years transportation, and followed the pattern of Newgate, Ceres and the Alexander, arriving in Sydney in January 1788. He was mustered aboard ship and did not die during the voyage, but there are no records of him in the colony and it is thought that he may have been one of eleven men recorded as ‘absconded’ soon after landing. (Now there’s a story for a novelist and a Netflix series!)

Perrott, Edward Bearcroft, see Wm. Connelly

NEAL(E), James, c1769- ? & *FARLEY, William, c1770-?

Two teenagers convicted together at Bristol on 10 February 1785 for the theft of two pounds of sugar and sentenced to seven years transportation. From Newgate they were transferred to the Censor hulk and then to Friendship.

Neale, recorded by Ralph Clark as ‘Jas. Neel’, was by then eighteen. On 6 March 1789, he and six other convicts absented themselves from their work at a brick kiln, left the confines of the settlement with the intention of looting fishing tackle and spears from the nearby Eora tribe. One account says there was a melee in which one of the convicts was killed and the rest injured. They were rounded up and each sentenced to 150 lashes and to wear leg irons for a year.

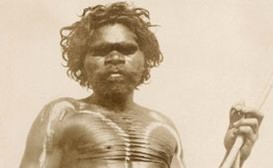

The bloody event was designed to show the indigenous people British ‘fair play’; that wrongs committed by either side against the other would be punished with equal severity. An indigenous Australian, who had been in the settlement about four months, was forced to witness the flogging. Not surprisingly, his reaction was ‘disgust and terror’.

The man was Arabanoo, the first ’aborigine’ (now an offensive term) to live among the arrivals, if it can be called ‘living’, for he had been kidnapped by a scouting party and brought to the settlement tethered and handcuffed. Originally he seemed delighted with the handcuffs, possibly thinking they were ornamental bracelets but became ‘furious’ when he knew their true purpose. The abduction had been deemed ‘essential’ by Governor Phillip, with the idea of teaching the captive to speak English so that he could act as a go-between between the occupiers and the occupied, and report ‘the advantages of mixing with us.’ (Look how civilised we are!) Arabanoo was not a particularly adept student and it may be assumed from his terrified reaction that the gross spectacle he was compelled to watch had the opposite effect to what was intended.

There is no further mention of Neale and he may have died from the flogging or from smallpox. Arabanoo himself succumbed on 18 May 1789 aged about thirty. Col. David Collins wrote an obituary note:

No contemporary drawing of Arabanoo appears to exist. Acknowledgements for the above to https://www.britannica.com/topic/Australian-Aboriginal/Leadership-and-social-control

‘His death was to the great regret of everyone who had witnessed how little of the savage was found in his manner and how quickly he was substituting in its place a docile, affable, and truly amiable deportment.’

The smallpox spread to the local population who had no immunity to the new disease and about 2,000 died.[1] In addition, convicts would soon launch vigilante attacks on the same clans who lived in the vicinity of Botany Bay.

Arabanoo was followed by other captive ‘natives’ including the notable Bennelong whose fascinating story can be read on Wikipedia.

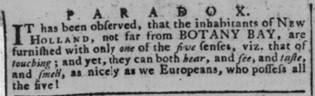

The Hampshire Chronicle had a strange contemporary view concerning the indigenous inhabitants of Botany Bay. (11 Dec. 1786).

William Farley, listed by Clark as Fairly, was about 15 when originally sentenced. He accompanied James Neale to Newgate, Censor and Friendship. He went to Norfolk via the Supply in 1790, and sustained himself on a one acre plot. By 1792 he was off stores and working for Norfolk Island settlers. He left Australia in 1793 to work his passage home to England as a seaman on the return journey of the convict ship Kitty.

WILTON, William, alias Whilton, Wilson, c1741-1787, at 43, was the oldest of the Bristol men. He was convicted at the QS on 12 July 1784 for the theft of 18 turkeys from a Mr. Ward. His death sentence was commuted to seven years transportation. Before the Fleet sailed he fell overboard from the Alexander and drowned 28 March 1787. As the prisoners were heavily ironed he would have had little chance of saving himself.

*WISEHAMMER, John, c1772-? Friendship. After his earlier misadventures in Bristol, (see Chapt.2) John was convicted on 10 February 1785 for stealing a ball of snuff. This resulted in a sentence of seven years transportation, a final sojourn in Newgate and removal to the Dunkirk hulk where his behaviour was ‘tolerably decent and orderly’. When he was delivered to Friendship in 1787 Ralph Clark recorded his name as ‘Jno Wisihamer aged fifteen’. This is not the only time he is mentioned in the Journal. On Friday, 10 December 1790, on Norfolk Island, Clark wrote

‘walked out to Charlotte Field twice – Jno Nowland and Wisehammer two carpenters were punished out there for neglecting there work – the former received the whole of his punishment, 50 Lashes but Wisehammer could only bear 8 Lashes; the Surgeon said he could not bear more he fainted away twice.

‘Saterday, 11th – went out to Charlotte Field before breakfast which I carried with me. Returned to dinner – nouland and wirehamer two Convict Carp. Which were punishd Yesterday for Neglect of of duty have not been at work since – Reported them to Major Ross at my Return who orderd the Store Keeper to Issue only half allowance to them.’

On the other side of the world John met an old friend, Shuke Milledge (Lady Julian) who he had known in the ‘good old days’ at Newgate. They moved in together on the island. Shuke will have her own chapter, so we shall meet John again.

Clark and Wisehammer appear as characters in Thomas Kenneally’s novel, ‘The Playmaker’, based on real life events, and subsequently dramatised by Timberlake Wertenbaker as ‘Our Country’s Good’. The fictional Wisehammer bears little resemblance to his factual self.

Statistics: Why were the Bristol men transported?

Eight were convicted for stealing men’s apparel and accessories including breeches, a waistcoat, boots, buckled shoes, spurs, gloves and a walking cane. This was a complete surprise to me. Perhaps their own clothes were in rags, or being young, they had aspirations of cutting a dash. The remainder were convicted of a wide variety of thefts: jewellery/watches, money including ‘promissory notes’, tobacco/snuff, 18 turkeys, two bales of linen, a looking glass, an empty pocket book, and simply ‘a felony’. Of these two were additionally charged with mutiny and of threatening violence. One attempted a street ‘mugging’ without success.

Almost all seem to have had a previous court appearance; some of these had been ‘whipped’.

What came later?

One died before the Fleet Sailed

One absconded on arrival in 1788; One similarly went missing in 1792. It is probable both soon died in the vastness of the Bush even in the unlikelihood they were found and nurtured by friendly tribes.

Three died within hours, days or months of their arrival.

Seven left the colony when their time expired, several in named ships to work their passages home. Out of these one definitely succeeded but was so disillusioned after a few years in England he petitioned to return to New South Wales.

Nine remained in the colony with varying success, running the full gamut from premature death (well before sentence was completed), to a lifetime of punishment, even up to respected government employee.

The last word : A cruel joke:

- On Sat 26 January 1842 The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiserreported

- ‘The Government has ordered a pension of one shilling per diem to be paid to the survivors of those who came by the first vessel into the Colony. The number of these really ‘old hands’ is now reduced to three, of whom, two are now in the Benevolent Asylum, and the other is a fine hale old fellow, who can do a day’s work with more spirit than many of the young fellows lately arrived in the Colony.

- ‘The names of the three recipients were not given, and is academic as the notice is false, not having been authorised by the Governor. There are at least 25 persons still living who arrived with the First Fleet, including several children born on the voyage. A number of these contacted the authorities to arrange their pension and all received a similar reply to the following received by John McCarty on 14 March 1842:

- ‘I am directed by His Excellency the Governor to inform you, that the paragraph which appeared in the Sydney Gazette relative to an allowance to the persons of the first expedition to New South Wales was not authorised by His Excellency nor has he any knowledge of such an allowance as that alluded to.” (signed) Deas Thomson, Colonial Secretary.

Supposing the above had not been a hoax, none of the Bristol men would have been eligible, as none were alive in 1842. Our most aged survivor was my imagined dandy, Stephen Martin who died in 1829 aged 81.

References:

[1] Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal, 13.3.1784

[2] Derby Mercury, 16 Jan. 1783

[3] Bath Chron 15.2.1787. ‘William James, London carrier, 76 Old Market’ is in Sketchley’s Directory of Bristol, 1775,

[4] For Eliz. Lock’s story, see 4b.

[5] Controversial. How smallpox arrived is a subject of much argument between historians.

Notes on sources:

I have drawn heavily on published research by previous historians:

Chapman, Don: 1788. The People of the First Fleet (1986)

Gillen, Mollie: The Founders of Australia: A Biographical Dictionary of the First Fleet (1989)

Mackeson, John F, Bristol Transported (1987)

The Journal and letters, of Lt. Ralph Clark 1787 – 1792 edited by Paul G. Fidlon & R.J. Ryan, published by the Australian Documents Library, 1981

https://peopleaustralia.anu.edu.au/biography/dennison-barnaby

https://www.fellowshipfirstfleeters.org.au/crowdersarahdavis.htm

https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/crowder-thomas-restell-1939

https://www.fellowshipfirstfleeters.org.au/joseph_elliotttrimby.htm

http://www.fellowshipfirstfleeters.org.au/stevenmartin.htm

https://firstfleetfellowship.org.au/convicts/richard-morgan/