My sister-in-law has just acquired a black Alsatian puppy in place of my brother’s old dog which died recently. I asked the pup’s name. She said: “Brunel! You know he was Colin’s hero?” Yes, I remembered. When my brother was on Desert Island Discs, (I’m not boasting here: no. 63 in the category “Space Scientists”, [BBC DID Website]) his luxury item was a picture of The Clifton Suspension Bridge. What’s this to do with my invitation to the launch of the newly accredited

you may ask? Well, the name Brunel, obviously, but Colin Pillinger? (Beagle 2 anybody?) Although the circus may have moved on in more recent times, he still comes up regularly in lists of “famous Bristolians”; Archie Leach definitely was one, but Brunel and John Cabot weren’t actually native, and Colin was always careful to say he was not a Bristolian either, as he was born in Kingswood, a place which has always been that little bit off centre. And he kept the accent too though without most of the vernacular. When I received the invitation to the “do”, almost simultaneously with the news of the coming of little Brunel II, it seemed like CTP was getting through from the ether.

I thought I knew Bristol, but (shame!) before the invitation, I had not even known a Suspension Bridge Visitor Centre existed. It has recently received full Accredited Museum status from the Arts Council, a prestigious award recognising the highest management, education, access and care of the historic documents in the Trust’s collections. I was among those privileged to be asked to the celebration to its relaunch as The Clifton Suspension Bridge Museum.

Along with the other guests I was greeted by our hosts, Jonathan, Natalie, Trish, Hannah, Laura and I suspect more, but I’m bad at names unless I write them down straightaway, apologies if I have missed anyone out. You were all terrific. Thanks too to smiley Jas-the-Camera whose jacket I coveted and to a young man who may or may not be called ‘William’. His enthusiasm and questions reminded me of my son (my tonight’s ‘plus one’) and my aforesaid brother when they were of a similar age. ‘William’ and I bookended the visiting squad, as the oldest (87) and youngest (10) in the party. The Museum has something for everyone. I spoke to a charming, friendly lady at the buffet and in explaining why I didn’t partake, (don’t ask), advised her earnestly to “look after her teeth” (she kindly assured me she did so) before I realised, I was talking to Peaches Golding, the Lord Lieutenant of Bristol, H.M. King Charles III’s representative in the County. I am my father’s daughter. Dad often came out with alarmingly inappropriate remarks, but never worried or felt embarrassed. Mum would say to him, “What did you say that for?” to which he would reply “I dunno. Just making conversation; they don’t take no notice of I,” (he was not an oik, this is Kangsood speech) but later Mum would tell me, “I went as red as fire. I didn’t know what to do with myself.” So, sorry Peaches, please forgive the lèse-majesté. It’s genetic. I just can’t help it.

Watched keenly by the life size sculpture of Brunel complete with trademark cigar which dominates the exhibition floor, there was just enough time for me to make a foray round the artefacts, stopping to take a photo of an (unusually intact) clay pipe.

I think of cuss words reverberating down the ages from the workman who dropped it. It must have escaped destruction by sinking into soft mud.

Nearby is displayed the tale of the miraculous discovery of the Vaults which had lain undisturbed for a hundred and fifty years. Briefly, in unscientific terms, our iconic Suspension Bridge is supported by abutments, huge structures two storeys high built of grey Pennant stone and surfaced with red Sandstone perching on top of the primeval rock. For years the abutments were thought to be solid or packed with stone rubble, but as no contemporary plans have survived no-one knew for sure. The foundation stone of the Bridge was laid in 1836, and it finally opened in 1864. Then more than a century later in 1969, engineers working on the “Leigh Woods Abutment” suggested it was hollow, but their bore hole hit only solid rock. The mystery remained. In 2001 the brickwork appeared to be under threat from a build-up of limescale which had to be coming from somewhere; surveys revealed a possible shaft but despite best efforts, no sign of a way in. Once again, the door to knowledge shut. Then in 2002, during resurfacing work a man named Ray Brown made a chance find. He noticed “a hole with what looked like a couple of railway sleepers over the top.” When he looked down, it seemed like a bottomless pit, pitch black. He said, “I put my measure down and there was a 15-metre (50 foot) drop!” His sharp eyes led to the discovery of twelve vaulted chambers within the abutments, thought to be the first elements of the Bridge, dating from approximately 1831, when the very idea of a bridge across the Gorge seemed madness.

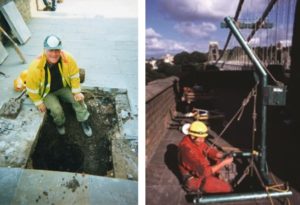

Ray (© Ray Brown) with the hole & John prepares to descend into the unknown. https://cliftonbridge.org.uk/going-underground-discovery-of-the-leigh-woods-vaults/ (© Clifton Suspension Bridge & Museum)

The rubble in the lower Chamber before it was removed. It was “hoovered” out using a suction truck and the site made safe. Though some is left to show the amount of it, see below.

Now, after drilling through two metres (6.5ft) of stonework, installing a doorway, and passage, two chambers have been opened for tours, something ITV reporter Rebecca Broxton in 2002 never thought would come to pass. “The shafts are too narrow and it’s too dangerous,” she said. She was wrong. The Vaults within the Leigh Woods Abutment would form the centrepiece of the evening. With a thrill of anticipation, I donned a hard hat and high-vis safety vest (always a GOOD SIGN where I’m concerned) and put my signature to a paper guaranteeing I could get up and down a vertical ladder and negotiate narrow passages. I am grateful my hosts accepted my word for it without a qualm. (So far, I have not been denied. I am not quite beyond such adventures and have recently adapted for use the prayer of St Augustine about another fundamental activity, “Please God, not yet!”) Thus, I went to it, light of heart if slow of pace. As we crossed the road and descended the irregular gravel and then the muddy steps of the path, the Heavens opened in reply.

A kind person looked after my walking stick so I could grip the rails at each side of the metal steps (which plunged about 10 feet to the depths) with both hands. Then, a short walk on an uneven surface took us to Vault No. 4, the first chamber we were to visit. It is monumental. No-one could help but be impressed by the precision and pride in workmanship with which the high arched chamber had been fashioned, the skill of the masonry, the fine brickwork, and then imagine the background noise of the picking, shovelling, hacking and drilling of the rock, and the gallons of sweat expelled by the workers. (How many un-named workmen later died of silicosis from the dust I wonder?) It had been made to last – forever perhaps. No provision for maintenance. When the men had finished each chamber, it was sealed up with no entrances left. But they were not that houseproud; they left the rock, blasted and dug out, behind them when they left.

After all, no eyes were expected to look upon the Vaults again – ever. The first modern explorers for over a century and a half who went down found the waste rock and stone still in heaps on the ground. With their way lit only by head lamps, they must also have muttered “What the Hell….?” as their boots crunched through calcite stalagmites growing on the floor, or so I thought.

Peaches Golding, OBE, PStG, Lord Lieutenant of Bristol, & another visitor to the Vaults

Hard hats were certainly required for the next stage, as we needed to bend double through the short tunnel, dug through by modern excavators to get to Vault No. 5. There is always something special about a tunnel. You never know what you will see when you come out on the other side. My mind here wanders back sixty years or thereabouts, when I was similarly bent in two, to get through another short tunnel, which opened into a much older chamber, where I was overwhelmed with awe, not for what the chamber contained, which was very little, but for what it meant in human history. I never expected when I straightened up on this present occasion I would be similarly affected. I blinked and found myself in A CATHEDRAL. Words fail. You can say all the “Wow!” You like, and all the “I never expected that!” but it simply doesn’t convey. Silence and wonder. I have never been able to do the previous experience justice either.

It is not a cathedral of course, but a huge, beautiful, silent space, a sister to the first chamber, but VAST. It is like the Tardis, seemingly bigger on the inside than out. Taller than three double-decker buses, I’m told. Cool from the water dripping from the roof. Do any minute water organisms survive in the water which drips through the brickwork? In the fulness of a million years or so might they evolve into monsters and burst out of the abutment? Otherwise, it is sterile. In the darkness no life exists. No insects, no plants. One would usually find this unnerving. When the lights are turned off the darkness is total. To keep it pristine those who maintain the space these days must clear away any tiny invading plant life that may dare to germinate and cling to the fittings of the electric lights. In both chambers spindly pencil-like stalactites hang from the roof, echoed on the floor by their non-identical twins, the small fat stalagmites.

“How did we find how far it went down?” asked our guide expecting an answer. “A stone?” I said, clever, clever. No. “A bigger stone?” said somebody else. Not to be outdone, I addressed young William who had asked the most interesting and pertinent questions throughout. “A child!” I said, thinking of Victorian chimney sweeps and the puny little Kingswood mine boys, sometimes only seven years old, preferred because of the narrow seams would do. The lad looked interested, but wrong again. This was the present day. A quartet of adult male adventurers had gone down the first time.

One of them, Guy Barrett, began his tale “I was lowered down through the hole, about 20 feet. There was a tunnel going out horizontally either side, just about big enough for me to get through. They carried on lowering me down about 40 feet and there was another set of tunnels leading out horizontally either side, then another 20 feet, down again to rubble at the bottom of the brick shaft which opened into a chamber 30-40 feet high and wide. As soon as we got to the bottom of that, all sorts of other tunnels led into a sort of honeycomb. The real sense of excitement was going somewhere nobody had been since the Victorians!”

Stalactites hanging from the roof and ………….Stalagmites growing from the floor of the chamber.

(For the unabridged story of Guy and others, see: https://cliftonbridge.org.uk/going-underground-discovery-of-the-leigh-woods-vaults/

A bright light shone through a totally circular shaft in one of the walls which looked inviting, just about the size for a ten-year-old to get through. William was obviously interested in having a go. The guide said “If you did, there would be a nasty surprise at the end. A twenty-foot drop.”

A bright light shone through a totally circular shaft in one of the walls which looked inviting, just about the size for a ten-year-old to get through. William was obviously interested in having a go. The guide said “If you did, there would be a nasty surprise at the end. A twenty-foot drop.”

We were sadly near the end of the tour of the Vaults, and until a new party is taken down, they will go back to black and silence, and the chamber will be alone in the dark again.

There was more to see before we left the Museum – the priceless collection of manuscripts and drawings.

We had the chance to handle stalactites which had broken off from the roof of the Vaults, calcified and brittle, which resembled stubby dead man’s fingers.

We had the chance to handle stalactites which had broken off from the roof of the Vaults, calcified and brittle, which resembled stubby dead man’s fingers.

The Suspension Bridge quickly became a tourist attraction, and just as today’s tourists take home mementoes of their visit so did the Victorian visitors. We were able to handle some of the original trinkets.The Victorians had mastered 3D via optical devices and period Magic lantern slides were enjoyed by others, but unfortunately not a lot of good to me having only one eye.

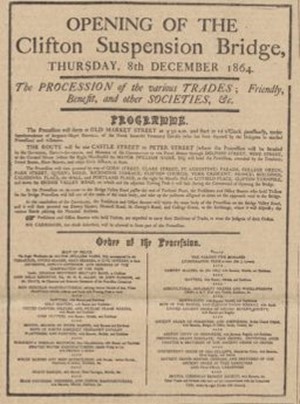

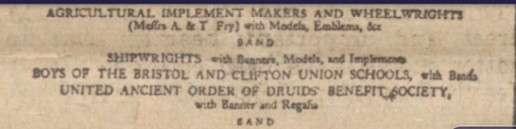

The appearance of Druids among the variety of worthies who took part in the Grand Procession on 8 December 1864 when the when the Bridge was opened caused amusement and bafflement. Why Druids? Who were they? Did they have Druids then?

The appearance of Druids among the variety of worthies who took part in the Grand Procession on 8 December 1864 when the when the Bridge was opened caused amusement and bafflement. Why Druids? Who were they? Did they have Druids then?

(For once, I kept Schtum. They had heard enough of me for one evening. Such Charitable & Friendly Societies were fashionable in the 19th century; Freemasons still survive, as I think do The Oddfellows, but I don’t know about The Buffaloes, The Grand Order of the Moose and any number of others, including Druids, unless at Stonehenge for the Solstice.)

Handbill of 8 December 1864, with Druids, reproduced in the Western Daily Press, 16.2.1924. (Thanks to WDP & FindMyPast.)

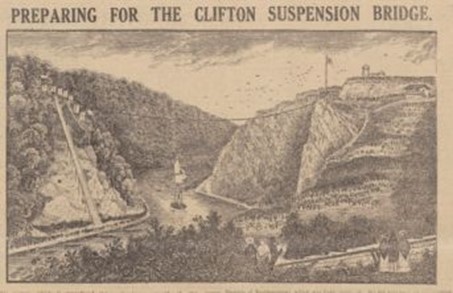

There are three women named in the current catalogue, but as usual most of the manuscript pictures depict important famous MEN, rarely of working people, white or black, hardly ever women. So, I thought I would throw in a few women from the day the foundation stone of the Bridge was laid in 1836. I don’t know whether the original of the next sketch is in the Museum’s collection. I didn’t see it on the day but spotted it reproduced in the same edition of the WDP, as above, in 1924.

I am intrigued by the apparent funicular roadway going up the steep side of the Gorge and what seems to be a collection of small houses teetering nearby on the edge. Did the workers building the abutment have to live up there with accommodation thoughtfully provided?

I am intrigued by the apparent funicular roadway going up the steep side of the Gorge and what seems to be a collection of small houses teetering nearby on the edge. Did the workers building the abutment have to live up there with accommodation thoughtfully provided?

The ground level spectators are stick insects but my interest lies in the back view of six other onlookers, enlarged:

two well-to-do women in bonnets and a chap in a top hat, and standing apart from them, three other women in shawls and head covering, possibly less posh, showing they knew their place. It is hard to tell if this is her face or the back of her bonnet, but one woman may even be turning to speak to us!

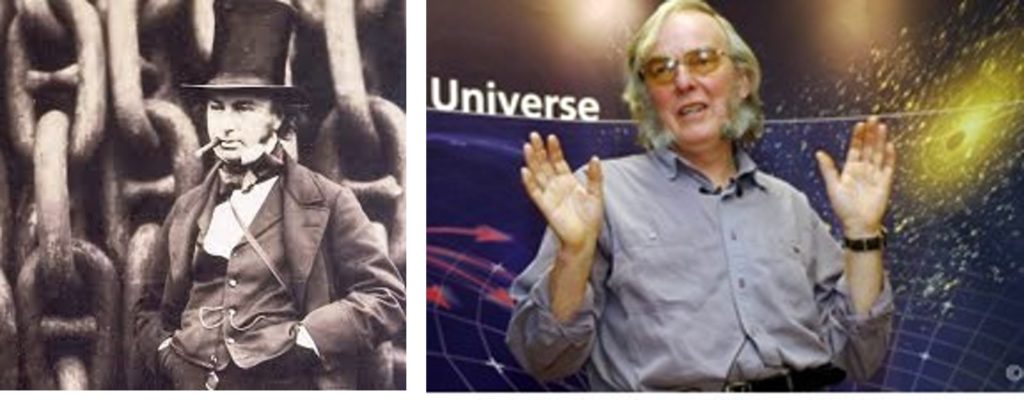

Later that night, in bed, with adrenaline still bubbling, I went back to thinking of Isambard Kingdom Brunel and my little brother Colin Trevor Pillinger, who both struggled on through ailments and adversity but died suddenly with so much more to do. They were also far too driven ever to sit quietly in the World of Shades, engaging in small talk but nevertheless, here they are:

IKB: “I couldn’t believe it. I died before I saw the Bridge built.”

CTP: “Nightmare. So did I.”

IKB: “Never! Don’t tell me you built a bridge too?”

CTP: “No.” (modestly) “Landed on Mars.”

IKB: (incredulous) “No….?!”

CTP: “Well, not me personally. Beagle 2, I mean. I died without knowing ‘the dog’ had made it after all. Touched down on the surface. But no signal. The perisher didn’t bark.”

IKB: “I say, old chap, what rotten luck!”

CTP: “But it’s still the only British spacecraft to land on another planet in our solar system. I would have liked more time though.”

IKB: “Me too. They used to call me ‘The Reckless Engineer’.

CTP: “They used to call me a ‘Waste of – ahem – Space.’ Sorry.” (grins ruefully) “‘A Waste of Money’.”

IKB: “My bridge is still there though.”

CTP: “So’s my Beagle.”

Both together: “Small Mercies.”

They nod sagely.

My Haiku:

“Lost Beagle on Mars.

He comes to heel. But too late

His Master is dead.” (© DPL)

________________________________________________

There is an avalanche of materials online for both men. Why Beagle 2? HMS Beagle was the ship in which Darwin went round the world, 1831-36. For “CTP”, Colin Pillinger, FRS, CBE, especially try, https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsbm.2023.0032

Two greats who helped put Bristol on the World map. There must be something about having impressive sideburns!

With thanks to his colleagues Ian Wright, Professor of Planetry Sciences, Open University, & Monica Grady, Professor of Planetry & Space Science, Open University. Their article entitled “Colin Pillinger was not one to compromise or toe the line,” may remind you of someone else. https://theconversation.com/colin-pillinger-was-not-one-to-compromise-or-toe-the-line-

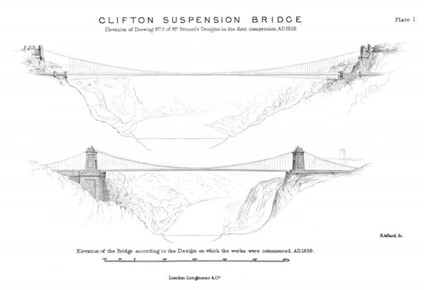

Brunel’s original designs for the Suspension Bridge

Mock up of Beagle 2 in our living room, c2001.

Some of the other pictures I took on the day. The rest are by courtesy of the BBC & Clifton Suspension Bridge Trust.

Websites abound see:

https://cliftonbridge.org.uk/visit-explore/visitor-centre/book-a-tour/

https://cliftonbridge.org.uk/museum-accreditation/

…..and in case you are remotely interested, the other tunnel I mention in the text was to the burial chamber of the Great Pyramid of Cheops. Better still, with just the guide and one other person, I had it to myself. No chance of that now. It was in 1965.

Leave a Comment