Like to the lark at break of day arising, (from sullen earth) sings hymns at heaven’s gate

Sonnet 29, Shakespeare

It is not strictly true to say I had never seen the Chalk Horses of Wiltshire, but I had only barely glimpsed one or other when travelling in cars, on other routes, to other destinations, or, as in the mid-1980s, when out sleuthing for any sign of the Pillinger family, I came to near proximity of the Cherhill Horse.

My visit to Cherhill village in that far off time, followed on from a trip to Bitton, where a few weeks before, I had been in a chilly turret room at St Mary’s church, scrabbling through the Parish Chest, fingers trembling from a mix of anticipation and cold. An index had revealed that the historical “Settlement Papers” referenced two generations of my direct kin, Nathaniel and Sarah Pillinger, and their children, John and Betty. The Laws of Settlement controlled the movements of the poor, so they did not burden the ratepayers anywhere other than in the place they were legally “settled”. If they ever fell upon hard times, they were at the mercy of petty officialdom, the “peaked-cap brigade” who, with pursed lips, could remove them in a whisker.

My ancestral family of four wandered into Bitton vestry in November 1754 where Nathaniel presented the document showing his legal place of settlement was the village of Yatton Keynell in Wiltshire. What happened in the next months is a blank but less than two years after they arrived, the parents, both only about forty years old, were dead and in the ground within weeks of each other. The Parish Overseers lost no time in getting rid of the younger, more likely encumbrance, Betty, by then aged twelve, who was “removed” to Yatton Keynell, her father’s birthplace and legal domicile, where she had never lived and perhaps knew nobody. Her likely fate was as an “apprentice”, taken in by a local family, “to learn the art and mystery of housewifery for seven years or until marriage” for which they received the penny and the bun, a parish stipend for their trouble, and what amounted to an unpaid life of drudgery for the girl.

John, who must have found work, was tolerated in Bitton until he was eighteen, then, in 1759, he was required to make a declaration in which he said he “thought he was born in Cherhill”, hence my pre-internet, in-person trawling the village that long ago afternoon for any feelings of ambience.

Not apparently being a liability, John was allowed to stay in Bitton pro tem, but he inherited his father’s settlement at Yatton Keynell, from which repercussions echoed down the decades; enforced to-ing and froing between Bitton and the Wiltshire parish if any of the progeny, including wives and children wherever they were born, became reliant on parish funds. The association with Wiltshire only ceased in 1848, when the latest John, an old man, grandson of the first, and my 2xgreat grandfather, who had been born in Bitton died in the Workhouse, not in nearby Keynsham, but Chippenham. [1]

Disappointingly there was no sign of my family in Cherhill, not even mystical. I have no reason to doubt John, but the sojourn must have been brief. He was most likely born in a barn. “They be strangers; ‘eave a brick at ‘em.” I was retrospectively miffed at the imagined inhospitality of the late denizens of the village and as for their stupid Horse, (not as antique as one would think, though it is the second oldest in Wiltshire), it seemed to be gloating from the hillside. I could easily have climbed the hill there and then to get a close-up view, but I chose not to. If John had been in Cherhill at all it had been forty years before the Horse was cut into the turf. Nowt to do with me.

My horizons are broader now. You would think, if only to correct this petulant omission, a nod to the Cherhill Horse would be first on the agenda for the latest leg of my 2024 birthday travels, but we selected the Westbury Horse first, despite there being no family association.

My horizons are broader now. You would think, if only to correct this petulant omission, a nod to the Cherhill Horse would be first on the agenda for the latest leg of my 2024 birthday travels, but we selected the Westbury Horse first, despite there being no family association.

Glistening in static pose, well defined, with a black beady eye, edged round in stone, we could almost touch the Westbury Horse from the place my son Kevin and I stopped on the steep escarpment of the eon’s old hillfort of Bratton Camp. It was love at first sight. In the buffeting wind, with larks ducking and diving high above us and singing, it was impossible not to whoop along with them, flap your arms and attempt take-off. It was bliss.

I resisted temptation to stumble down the slope for a nearer acquaintance with the Horse. Imagine if Kevin had to attempt carrying me back up? Or worse, the ignominy of a call out to the equivalent of the Downs “Mountain Rescue”. I would have liked to have walked the camp. I regret all the walks in my life that remain unticked, but thanks to “Fred” the author of “Two Dogs and an Awning”, I can see what I was missing:

I tell anybody who will listen, “Gather ye Rosebuds while ye may”. The Universe is so large, and our time is so short.

The Horse was, by tradition, cut by order of the Earl of Abingdon, probably the fourth Earl, who had estates at Westbury. He seems to have been something of a dilettante, an arts and music buff, who, (and this is not meant as a warning to Kevin), died broke in 1799. “Fred” is the only person within much googling to suggest that the wonderful “Mr Gee” who in 1778 cut the Horse from the hillside had a first name – George. He may be the George Gee, son of James & Susanna, baptised in 1755 in Rowde, just over 10 miles from Bratton, but at twenty-three he seems absurdly young (though no doubt agile enough) to have carried out such skilled work. Not that it could have been a one-man enterprise; he must have had a gang of measurers, scythers, cutters, carvers, scrapers and shovellers with him. Before they could even start, they had to erase an older figure, of which only a sketch remains. It faces the opposite direction, has a drooping belly, a saddle, a fish like tail, legs without hooves, and looks worried, poor thing. The “surviving sketch” must be a hoax (no-one drew anything like this in the 18th century that I’ve ever seen.. Beware of Wikipaedia!). If a previous horse figure existed, which is probable, it was almost certainly nothing like this, but if it did, I can quite see that it might embarrass the earl when he entertained. There is no sign of the original horse now, whether in “pantomime” or any other representation.

Pantomime Horse, sketch of 1772 (or was it?) From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Westbury_White_Horse

Mr Gee’s Horse has undergone modifications over the years, plus other adventures. It was completely covered in WW2 so that enemy bombers could not use it as a landmark. In 1957, it was concreted over and painted white, an extreme method of preservation to prevent further erosion. You are not really looking at a Chalk Horse at all.

Does it matter? Discuss.

Before we drove away, we listened to the sublime “The Lark Ascending” a fitting finale, even when punctuated by an occasional salvo from the Army guns, carried on the wind from Salisbury Plain, a jolt back to the present and the bloody horrors elsewhere in the World.

Me outside “The Admiral” barge

The family history connection with our next destination, is vague: one Pillinger branch line, unrelated as far as I can tell, were canal boat people on the Thames & Severn Canal at Lechlade.[2] I expected the Kennet & Avon Canal would give me a gist of their way of life.

We were off towards Devizes for the Caen Hill Flight, not that I was about to (almost) take to the air for the second time that day. The Flight is an almost

unbelievable feat of engineering, a triumph of ingenuity and optimism, the twenty-nine lock system of part of the K&A, a stretch of more than two miles, which raises the Canal 237 feet, a gradient of 1 in 44. To navigate in a boat, it takes up to five or six hours, and, I suggest, a lot of patience and good humour. We concentrated on the middle sixteen locks, the steepest section of the Flight but stuck to walking the towpath.

We called first at the exhibition on board “The Admiral” barge, which satisfied my desire to get a general idea of how “my own” people at Lechlade would have lived.

The architect of the stupendous feat of engineering was John Rennie, thirty years old who like so many engineers (at least by tradition) was a Scot. The K&A occupied him between 1794 and 1810 and included the Dundas Aqueduct, the Caen Hill Locks and further along the route, a 4,312 yards long tunnel.

The architect of the stupendous feat of engineering was John Rennie, thirty years old who like so many engineers (at least by tradition) was a Scot. The K&A occupied him between 1794 and 1810 and included the Dundas Aqueduct, the Caen Hill Locks and further along the route, a 4,312 yards long tunnel.

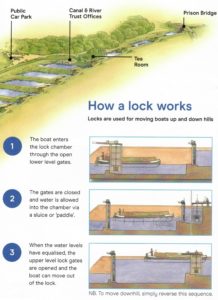

However much we are taught to revile coal nowadays, it fuelled the Industrial Revolution. Before roads were surfaced and a railway network established, the safest and easiest way to travel or transport goods was by water. As the 18th century demand for fuel grew, rivers had to be joined up by canals to transport coal, and canals were being dug all over the country. Locks were essential because they enabled boats to go up and down hills. This was not simple even without the further complications encountered by Rennie, whose brief was to join Bristol to Bath, (the River Avon was navigable) and London by an uninterrupted waterway. When the original planned route to leave the river near Chippenham proved unfeasible through lack of water, Rennie had to adopt an alternative. He diverted at Bradford on Avon and went through Trowbridge to Devizes, the latter section of which included a dramatic change in elevation which led to the Caen Hill Flight, joining the river Kennet near Hungerford.

How a lock works. By kind permission of ther Canal & River Trust (Fold-up guide to the Caen Hill Flight)

Locks were time consuming, expensive to build, required large amounts of stones, bricks and wood and a huge labour force, skilled and unskilled alike. Such men would be attracted to canal work as it paid better than farm labouring, and mostly came from the surrounding villages. They were called “navigators” because they navigated the waters. A few decades later the abbreviated form “navvy” became generic and stuck, especially when the frenzy for railway building began; by then men followed the work and came from all over the British Isles, including Ireland. Navvies developed a reputation as drunken ruffians, but like most of the rest of us, this was sometimes deserved, sometimes not.

I don’t know the names of any of the tough, hard-working men who built the K&A, so in future I will be keeping an eye out for them, in my crusade to name as many as possible of us “ordinary”, usually anonymous people.

The canal boom declined with the advent of the railways; steam was quicker and more reliable. The GWR, whose main concern was to promote its business of railways, took over the K&A in 1852. The company barely maintained it. (Pooh. Bah. Hiss!) A century later in 1955 the canal was in such poor condition that the British Transport Commission was prepared to abandon it altogether. It was brought back from the brink by fierce opposition from traders, boaters, enthusiasts and the general public, out of which grew the special place you see today. (Cheers!)[3]

It was a pleasure to see and talk to some of the friendly volunteers we met during our long slow walk down the towpath, from the exhibition barge to a welcome seat where we ate our packed lunch and looked back in wonder at the Flight. May I add a small plea here for an extra couple of benches along the route especially for aged historians and others for the use of.

It was a pleasure to see and talk to some of the friendly volunteers we met during our long slow walk down the towpath, from the exhibition barge to a welcome seat where we ate our packed lunch and looked back in wonder at the Flight. May I add a small plea here for an extra couple of benches along the route especially for aged historians and others for the use of.

When my son went to fetch the car, I left the comfort of the seat and walked through a small arch up to the bridge to wait for him. Four bridges cross the Flight, each one incorporating a smaller extra archway which allowed the horse which pulled the barge to go through whilst the lengthy business of the locks was in progress.

As we said goodbye to the locks and drove towards Cherhill rain started to fall.

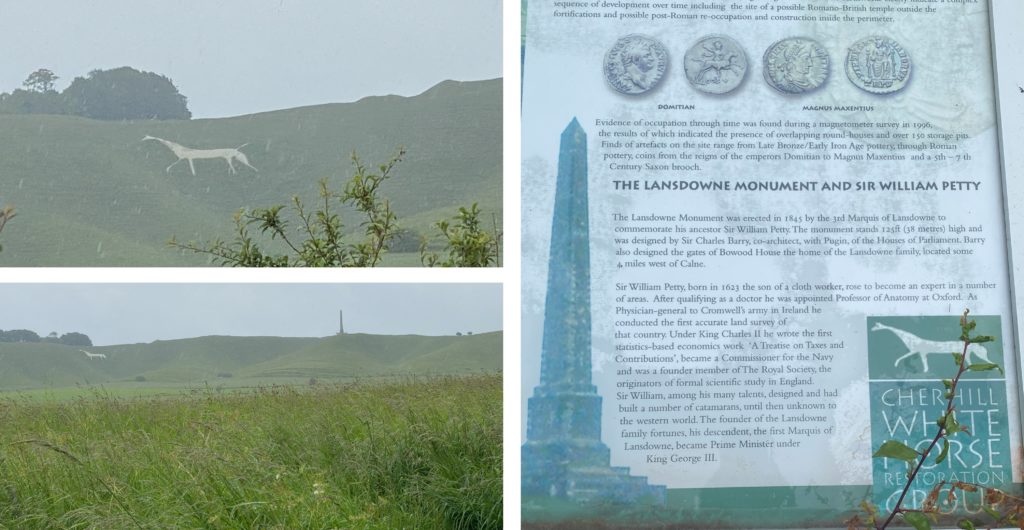

Despite the mist, we managed a good view of our second Horse of the day. I have to say it is sprightlier, if more quirky, than its Westbury brother. It is in full canter, with a high tail, an elongated neck and a tiny head. I felt a dart of remorse for not climbing up to it when I’d had the chance.

Despite the mist, we managed a good view of our second Horse of the day. I have to say it is sprightlier, if more quirky, than its Westbury brother. It is in full canter, with a high tail, an elongated neck and a tiny head. I felt a dart of remorse for not climbing up to it when I’d had the chance.

The Cherhill Horse was carved in 1780 by Dr Christopher Alsop. Long Live the English Eccentric. He is said to have shouted the instructions to his workers through a large trumpet from 100 yards south, though it is now considered unlikely that his voice would have carried that far. Possibly orders were relayed by semaphore.

The Cherhill Horse Restoration Group which maintains the Horse are rightly proud of their work. With a dig in the ribs to Westbury, they pinned this poem to the parish notice board:

“We could have paved it with cement and made it incandescent

But we did it properly, the way it was meant to be.

In winter chalk is grey, when the sun shines it’s bright;

A top dressing now and then will see the horse more white.

Please come and help us do, or give a pound, thank you.”

In Spring 2015, an anonymous reply was pinned next to it on the board:

“Thanks for your explanation, about the colour of the chalk,

-you’ve allayed the consternation I’ve been feeling on my walk.

But it’s not the colour that’s confusing, I’ll tell you honestly:

it’s the shape I find amusing, because a horse I cannot see!

What model there could’ve been for the head, I cannot guess,

the closest thing I’ve seen is, the monster from Loch Ness.

Its jaw is much too pointed the ears more like horns

its huge eye looks quite disjointed in the pin-size head it adorns.

The body seems peculiar, a strangely stretched out square,

and I’m looking for a stomach, but can’t find one anywhere!

All four legs are there I’ll grant you, but none of them look right:

too fat, too thin, to list just two; and not one a constant height.

The horse of Cherhill’s a landmark, a genuine tourist charmer;

but truth be known, chalk light or dark, it looks more like a mutant llama!”[4]

Charm is the word for our Wiltshire Horses, and much as I cherish them both, comparison with the elegance of the pre-historic White Horse of Uffington is futile! Is there a finer example of “Less is More”?

Near the Cherhill Horse is a monolith raised in memory of Sir William Petty, sailor, medic, academic, economist, philosopher, knighted by Charles II, who among his many accomplishments invented, designed and (presumably) sailed the first catamaran. He was born in 1623, qualified as a Professor of Anatomy, served with Cromwell as his surgeon-general in Ireland, and afterwards spent his last twenty years there. Despite his impressive CV he would not have found his way into this blog if not for a connection spotted by Kevin. Not a man to sit on his hands, Petty undertook the first official land survey of Ireland.

Why should that be of special interest to us? Kevin’s great-grandfather and my grandfather-in-law Lindegaard, a Dane, was one of the lithographers working for the British Ordnance Survey which mapped Ireland in 1901. He became “more Irish than the Irish”, as the saying goes. The latest incarnation of this comes in the Six Nations and it’s Ireland versus England. My husband and son are “Us” and I am “Them”. I don’t mind. Somebody has to stick up for the battered Anglo-Saxons.

Why should that be of special interest to us? Kevin’s great-grandfather and my grandfather-in-law Lindegaard, a Dane, was one of the lithographers working for the British Ordnance Survey which mapped Ireland in 1901. He became “more Irish than the Irish”, as the saying goes. The latest incarnation of this comes in the Six Nations and it’s Ireland versus England. My husband and son are “Us” and I am “Them”. I don’t mind. Somebody has to stick up for the battered Anglo-Saxons.

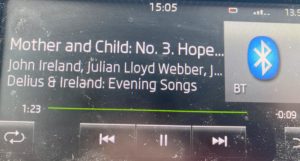

On the last lap of the day, by marvellous chance this came up on the car radio.

It was the perfect end to a lovely day. The gods must love us.

References

[1] For the full story, “From Little Acorns Great Oaks Grow”, https://www.bristolhistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/03/From-Little-Acorns-Great-Oaks-Grow-

[2] The Pillinger Family History Part 3, Chapter 5, page 122 &c.

[3] For further details: canalrivertrust.org.uk

[4] Many thanks to the Cherhill Restoration Group for permission to use their poem and its answer taken from their website. The Group always welcomes volunteers and can be reached via Rob Pickford 01249-822884 or 07917048680, or https://cherhill.org/parish-council/

Leave a Comment