Francis Creswicke, 1643-1732 (With grateful thanks to David Warwick who posted this portrait of his forebear on Ancestry UK. He has kindly allowed me to reproduce it for this blog.)

When I was a stripling of about 40, I first came across Francis Creswicke aged eighty-nine on a gravestone at Bitton, my paternal home parish.[1] Now I am rapidly catching up with him, though he will stay the same forever.

Francis was once the Lord of the Manor of Hanham Court, who, had things turned out differently, might have led a quiet life as a country gentleman. For all I don’t write too much about “nobs”, he has always been a favourite of mine, if only as a warning not to look for trouble. I intend to invite him to my spectral dinner party at Valhalla. The news that Hanham Court Gardens, his home ground, were open to the public on 9th June 2024, the very weekend my 87th birthday week kicked off, was a match made in Heaven. If it had been the following day, June 10th, we could even have celebrated the 345th anniversary of Francis’s wedding to Mary Ridges in 1679 at St Sepulchre’s Church in London. The marriage licence (June 6th) states that she was aged 25, a spinster, parents deceased, of St Bride’s, London.

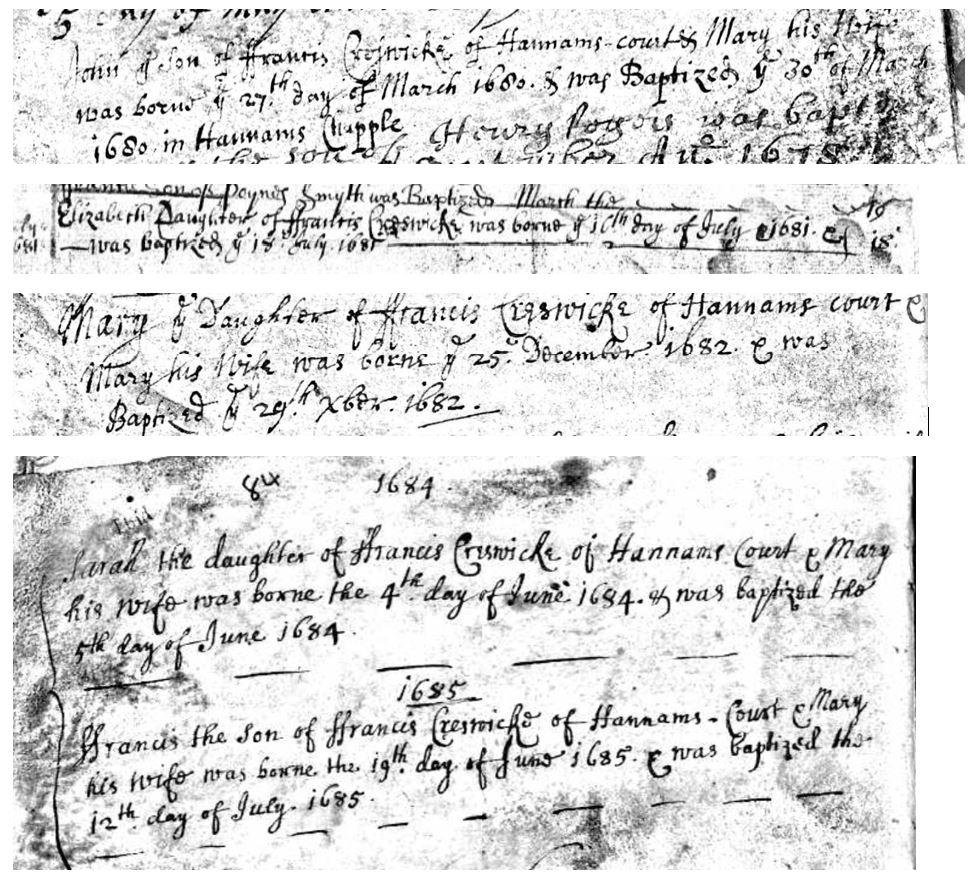

Little is known of Francis’s early life. He went up to Oxford as a teenager. He matriculated aged 16 and received a B.A. from Magdalen College. Aged twenty-three, he inherited Hanham Court from his father, and brought his bride there after their marriage. They produced eight children during the next ten years, John, 1680, Elizabeth, 1681, Mary, 1682, Sarah, 1684, Francis, 1685, Henry, 1686-1744, Geoffrey, 1688, and Florence in 1690. Most of the babies were christened at the little church adjacent to Hanham Court, a Chapel of Ease of “Kingswood’s” principal parish of Bitton.

The names of four of Francis and Mary’s children were inscribed in Latin on the Creswicke grave at Bitton, John, Godfrey, Francis and Mary, though undated. I assume they were infants or died young and their names were added later by their brother Henry, who succeeded their father, Francis. The fate of Sarah, Elizabeth and Florence is unknown.

Hanham Court was purchased in 1638 by Francis Creswicke I, (1584-1649), who achieved high office within the Society of Merchant Venturers as well as in local government. He was briefly Mayor of Bristol before the city fell to Parliamentary forces during the Civil War. His son Henry, also sometime Mayor of Bristol, bought the residue of the Manor of Hanham (c1653 during the Commonwealth period) which seems to have been when he came into conflict with his neighbour, Sir John Newton of Barr’s Court. The parties went to law where Creswicke prevailed. In 1663 he was knighted by the restored monarch Charles II out of gratitude for the family’s loyalty to his father. The Newtons were “old money”, and though Francis Creswicke had been raised “a gentleman”, his forbears rose through “trade”, and he may have been viewed as something of an upstart by the Newtons, but the worse part was that Francis inherited the bad blood between the two families.

Bear with me while I attempt a brief explanation of the complicated local circumstances. Modern Kingswood[2] takes its name from an area which once included St George, now a Bristol suburb whose original name was “St George, Kingswood” after its church, built mid-18th century, (demolished 1976); plus Hanham, Stapleton, and other surrounding lands which were inside a former Royal Hunting ground, the King’s Chase, otherwise the “King’s-Wood”. Though the area was in Gloucestershire, just outside the City & County of Bristol, the Constable of Bristol Castle was the Chase’s Chief Warden. He engaged rangers to keep order, but it was no sinecure. Repeated lawsuits failed to remove neighbouring landowners who made encroachments of the Chase affixing their own names to these lands, calling them “Liberties”. The Civil War and the destruction of Bristol Castle only exacerbated matters which had boiled for almost a century. The attraction for the landowners, the “Lords of Kingswood” was not to preserve the ancient forest but was to mine the coal under the ground. Previously, only the very poor burned coal, which had at one time even been banned by Royal proclamation. (The first “Clean Air” Act?) Now, an expanding City population, a shortage of wood and nascent industry created demand for coal, and thus profits to be made, from an area considered by some to be “waste”. The “Lords” sold unlawful leases to coalmining “adventurers” who staked their claims, and workers followed. The oaks were cut down, pits dug, the deer destroyed, and plots of land enclosed. The people who moved in erected rough huts for themselves and their families to live in and such “villages” grew up all over the forest. One of the principal “Lords” was Sir John Newton with three “Liberties”. In 1673 his Third Liberty alone, in the vicinity of the Bath Road, had twenty-three pits between Hanham and his Barr’s Court Estate open and working.

With the Restoration of the Monarchy, King Charles II rewarded two loyal supporters with the lease of Kingswood Chase, conveniently ignoring the adage that “possession is nine tenths of the law”, expecting “the Lords” to roll over by Royal edict. One of the two awardees declined the honour, leaving Sir Nicholas Throckmorton, who shortly afterwards died; the poisoned chalice was inherited by his nephew, Sir Baynham. Lawsuits and Court sittings failed to remove the incumbents. Mayhem erupted between the colliers/settlers – otherwise squatters, allegedly encouraged by Sir John Newton – and the rangers attempting to evict them, (our version of the “Wild West”). Their names survive in lists of squatters, fugitives, rioters, and “Keepers of Cole horses”. When Sir Baynham issued his last writ in 1681 five hundred acres of the Chase had been despoiled, there were two hundred coalmines in operation, upwards of three hundred cottages built and more than a thousand coal horses. After this he wearily died. His three daughters lost no time in selling the lease to……. of all people……. Francis Creswicke of Hanham Court.

Given the overall situation, plus the ongoing personal enmity between the Creswickes and Newtons, you must ask an obvious question. Why?

It smacks to me of someone who had always “wanted Daddy to love me”. Francis’s father and paternal grandfather were long dead, but they had been high achievers and maybe Francis felt he needed to make his own mark. He became a man with a mission. To restore the Chase. It’s almost a story of our own times. If he was alive now, we might even call him an environmentalist. He must have been aware that he would come up against enormous odds, not just the whole shebang of Kingswood’s “Lords”, and particularly the enmity of the latest Sir John Newton of Barr’s Court,[3] but neither would he be popular among the rank-and-file workers who needed to earn their daily bread.

It was about this time that Francis and I collided again at Bristol Record Office, via his memoranda, “The Inhabitants of Kingswood Chase, 1684”. This time he was in vigorous early middle-age, and I had fallen unexpectedly in love with coalminers. I need hardly say that Francis was not collecting information because he felt sorry for the Kingswood colliers, or to help a dilettante historian more than 300 years in his future, (especially one with divided sympathies between workers and nature) but he was gathering evidence for another tilt at law with Sir John Newton. I am entirely neutral in the dispute, (at least this far) but the data is invaluable. Thank you.

The notebooks are a revelation. The workings of pre-industrial revolution coalpits operating in the various “Liberties”; their locations and proprietors named, along with as many of the forest folk Francis, or his agents, could collar, male and female alike, excepting the young urchins who played amongst the slag heaps. The forty widows named must reflect the danger of coalmining life. Of the rank and file, the “under-ground men” in various guises are in the majority: coalminers, colliers, coal carriers, quarriers, plus the smiths, masons, carpenters, nailers, labourers, who were necessary aides. Work begets work. There were four ale sellers (naturally), three butchers, to slaughter the deer, by this time in diminishing supply, and sheep too, for there were two wool combers, (but no weaver), plus a number of other tradesmen, a baker, thatcher, tiler, cobbler, hatter and so on, even three Gentlemen, and a Minister, who must be one of the wary Baptists known to hold illicit prayer meetings in the forest.[4]

On 26 April 1685 William Braine and Henry Cheney, two keepers, reported on oath that in the previous two years three hundred deer had been slaughtered in the Chase and they “verily believed” that the destruction had been instigated by Sir John Newton & William Player, esquire, (another holder of “Liberties”) threatening “certain persons” to do the killing, “under penalty of being [for]ever banished from the coleworks, they and their families, in the pretended Liberties.” A case of either do as I say, or watch your children starve by the roadside. Francis went to law and carried the day. Sir John seethed for a short time but was suddenly dealt an unexpected ace. On 11 June 1685, the Duke of Monmouth landed at Lyme Bay in Dorset with a view to topple the Catholic King, James II. By the end of the month his small force had grown substantially into the famous “pitchfork army” and by 25th June they were encamped at Sydenham Meadow in Keynsham with a plan (not realised) to march on Bristol.

Hanham Court was in upheaval of its own. Not only was Mary Creswicke “lying in” having given birth to Francis junior six days before, but the Creswickes had felt duty bound to put up the Bridges family, Lords of the Manor of Keynsham, plus retainers, whose own premises had been appropriated by Monmouth as his HQ. Perhaps to escape the domestic clatter, and Sydenham Meadow being within strolling distance, Francis decided not to miss the chance of a first-hand view of the rebels. Considering this may have been the most exciting national event ever to occur in the neighbourhood, most of Keynsham and the parish of Bitton had the same idea. A man called Christopher Tilly, who Francis knew slightly, recognised him and handed him a pamphlet entitled “Reasons for the Taking Up of Armes”, saying “Keep it. You may learn.” Francis returned the paper unread, replying angrily

Damme, you presume on our acquaintance. Do you mistake me for a madman? And with all the country watching?

Tilly huffily withdrew and Francis thought little more of the incident, but the exchange had been noted by two of Sir John Newton’s servants, Cornelius Merry and Ben Hyett, who hurriedly left the field for Barr’s Court. Sir John felt it was his public duty to inform the Duke of Beaufort, (of course he did!) His Grace swore out a warrant and before the week was out Francis, and his man, George Sanders, were in custody at Gloucester Castle, charged with High Treason.

Gloucester Castle had been used as the County Gaol since the 13th century. By Francis’s time only the Keep where the prisoners were kept in grim conditions remained. This drawing dated 1819 is said to be a copy of a previous depiction of the demolition which began in 1787. Nothing remains now apart from the foundations which currently are not on public view.

Francis wrote a series of impassioned letters protesting his complete innocence and allegiance to the King, drawing attention to the “malitious contrivance” which had brought him to his desperate state, with his loyalty affirmed by statements from his influential friends in Bristol. The case was deferred and eventually dismissed on 13 January 1686 as the principal witnesses did not turn up, the inference being they had been paid by Sir John Newton to make themselves scarce. Francis returned to Hanham Court, hopefully with the unfortunate George Sanders, who disappears from the record. As is well known, many others were not as lucky.[5]

The following August, the Royal Family were in the West Country and were allegedly entertained under a tree in the gardens at Hanham Court. The king is said to have requested that a brace of deer from his Royal Chase should be sent on to him for the Royal Table in London. Francis frantically combed what remained of the forest without finding a single animal.

Two non-royals, George and me, under a tree at Hanham Court Gardens on 9 June 2024.

By 1688 James II had more to worry about than feasting. The gallons of blood spilt not only at Sedgemoor, but during the vicious revenge of the aftermath had been for nothing. Having dispatched his nephew under the axe a couple of years before, he was deposed and exiled in favour of his daughter Mary and son-in-law William of Orange. [6]

The despoil of the Chase continued unabated: as fast as Francis replaced the deer they were poached and killed for food. Petty claims and counterclaims were exchanged. In April 1691 Sir Richard Hart, one of the defendants in Francis’s latest suit complained in Parliament that three Kingswood men had been pressed into William III’s army. Unless they were released, he blustered, five hundred colliers would riot and refuse to deliver coal to Bristol. This proved to be hot air, and no protest materialised, but it shows that Kingswood’s reputation for lawlessness was growing fast. In October a desperate Francis was paying informers to give him evidence of deer slaying. He fined a Hanham coal miner, Nicholas Reed, £10, of which half was to go to the informer, and the other half between Francis and his co-lessees. As Reed had no money or property, he could not pay, so it was a pointless exercise. This may have been the last straw. The cost of continual litigation had brought Francis to ruin. In 1692 he mortgaged Hanham Court to James Marmion, a London goldsmith. When he could not keep up the payments Marmion took possession and “ejected the wife and family. Afterwards Creswicke took forcible possession; and from that time there were no end of lawsuits.”[7]

In 1698, the coalworks remained in full production. Celia Fiennes, the noted traveller, a relative of the Fiennes family of Siston Court, says “coming into Kingswood, I was met by a great many horses passing and returning loaded with coals dug hereabouts.”

Sir John Newton died in 1699. He was not all bad. He added a rider to the deeds of the Adventurers who bought his leases: “When pittes are fully wrought right out they shall be filled up and the ground levelled.” This was mostly ignored, and it was not unusual for the unwary to meet the angel of death via an unfenced hole. Even these days it is not unknown for a Kingswood resident to open their back door one morning and be confronted by a yawning sink hole.

Next for a mystery. Francis “was imprisoned at Dublin from 1704 to 1713 for stabbing with a skean (a short Irish dagger) on Sunday May 21st in the church of St. Andrew, after service, Robert Rochfort, Esq., Her Majesty’s Attorney General.” [8] Why Francis was in Dublin at all is not stated. I suspect Francis was a Tory and Rochfort a Whig but there must be more to it than that surely? Rochfort recovered and lived until 1727. Nine years is a long time to stay in gaol.

To paraphrase Ellacombe,[9] Francis was succeeded by his son Henry who also went to law about manorial rights with the latest Newton incumbent, Sir Michael. He was succeeded by his son, another Henry who was imprisoned for many years for debt. He left two sons Henry and Humphrey. Humphrey bought Hanham Abbots from his brother by whom he was imprisoned fourteen years in London for non-payment.

He goes on to attribute the Hanham Court family misfortunes to “Infelicity of Sacrilege a sad instance of the fate of those who possess monastic lands.” Sins of the fathers and all that.

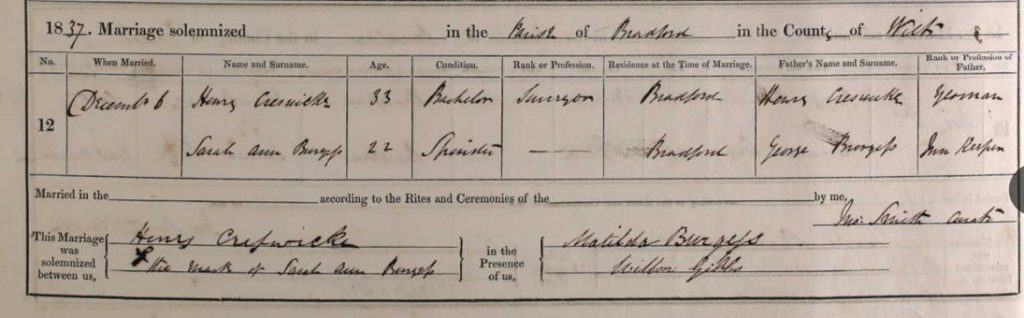

“Henry married Sarah Ann Burgess, the daughter of George Burgess, of the White Hart Inn Keynsham Bridge” says Ellacombe, below which he puts a simple downward arrow with the words “In Canada”, which hints to me of censure. My immediate thought was he might just as well have added “No more than they deserved.” But I may be reading too much into the Reverend’s somewhat dismissive comment, but whether it was for them or their destination I cannot hazard a guess.

The wedding between Henry and Sarah Ann took place on 6 December 1837, at Bradford on Avon in Wiltshire, perhaps to reduce the number of eyebrows raised over the marriage of a gentleman’s son (albeit a surgeon, but – sniff – not a physician) and an innkeeper’s illiterate daughter. The couple did indeed emigrate to Canada, and I retrospectively wished them happy lives in a new country. I understand their descendants have visited Hanham Court in more recent days.

Francis arrived home in Hanham, date unknown. He died on 18 January 1732 and was buried in Bitton churchyard. Of Mary his wife, it says she is buried in the same plot “aged 58”.[10] As we know from their marriage licence, she was aged 25 in 1679 [11] making her birth year 1654. If this figure is correct, she died sometime in 1712, so had lived without Francis throughout the Rochfort debacle and died before he was released, immensely sad, even though I’m guessing that he was not an easy man to live with or without. As is usual, History is mostly “His-Story” and we can only imagine how Mary endured the many difficulties in the life she shared with Francis Creswicke.

———–o.O.o———–

Further information:

Latimer, John, “The Annals of Bristol”, volume 1

Ellacombe, Rev Henry Thomas, “History of Bitton”, Part 1, plus his unpublished “Manuscripts” (17 volumes) at Bristol Reference Library.

With thanks to Amazon & Find My Past via whose pages I have filled many gaps including the parish register entries reproduced above.

[1] His age as carved on his tombstone at Bitton, recorded by Raph Bigland of blessed memory. See Bigland, Ralph: “Historical and Monumental Collections of the County of Gloucester”, 1786. (Ed. Brian Frith.)

[2] Kingswood, a town east of Bristol, not to be confused with Kingswood, Wotton-under-Edge.

[3] This Sir John was an adoptive heir, but nevertheless his zeal equalled that of his predecessors.

[4] I am preparing my own list of all these common people.

[5]For a heartbreaking minor moment in the tragedy of the Rebellion, see “Charmouth Tales: All he did was to sell Monmouth some fish.” https://www.bristolhistory.co.uk/?s=all+he+did+was+to+sell+Monmouth

[6] You think your family is weird?

[7] Ellacombe, Rev H.T. History of Bitton in the County of Gloucestershire, Part 1, page 139. [1881]

[8] Ibid. page 138. Ellacombe’s information seems to come from a petition to the House of Lords in 1711. See https://vlex.co.uk/vid/robert-rochfort-appellant-francis-805792281 If anybody can explain legalese, I would be grateful.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Bigland, op cit.

[11] The (published) marriage certificate gives Francis’s age as 30, though if his tombstone is correct then he was 36 in 1679 which could easily be mis-copied as 30. It must be remembered that generally nobody knew their right age, and their funeral age was guessed by those they left behind!

Blog Comments

Angie Allen

16th October 2024 at 4:01 pm

What an excellent story and brilliantly told. Thank you.

I am researching a link between a Mary Creswicke nee Dickinson (Bristol & Jamaica) daughter of Vickris Dickinson, who must have been married to one of those Henrys I think. Unfortunately I only have a rough birth date, sometime in the mid 1750s ….. I think.

Do you have any further info.?