Please Note: This post contains words which are no longer acceptable but were commonplace during the 2nd World War when these incidents occurred.

I cannot say that DOMILLE LUCIA JAMES is inspirational; in fact, her adventure stretches the boundaries of “foolhardy”.

I’m going to take you back to the dark days of World War Two and the perils of the North Atlantic convoys. For nearly six years there was total war. Unarmed Merchant ships shepherded by the Royal Navy kept the UK going with vital supplies. All the ships and their crews, (which may have included a few women) were in deathly danger from attack by the marauding German U-Boats. The USA entered the war in 1941 and from then on, the crossing included American ships carrying US arms and military personnel, among them women soldiers of black battalions like ‘Six-triple-eight’. Ships hit by a torpedo went down with all hands, or a lucky few of the crew might scramble into lifeboats to be picked up after hours at sea. Shivering, wet, ice cold, exhausted, terrified, in one such lifeboat was a young Bristol woman, neither military nor civilian, a stowaway.

Domille Lucia James was born in Bristol on 18 December 1919. Her official birth registration records her first name “Domealay”. Can’t you almost see the snooty clerk looking down his nose in disapproval at the brown baby and her Irish mother, who he made utter each syllable of the baby’s name in turn? If I’m charitable the official may simply have been puzzled. In any case he wrote down what he heard, phonetically. She has often been recorded as Domillie, but I believe her name was Domille, with a French acute accent over the ‘e’.

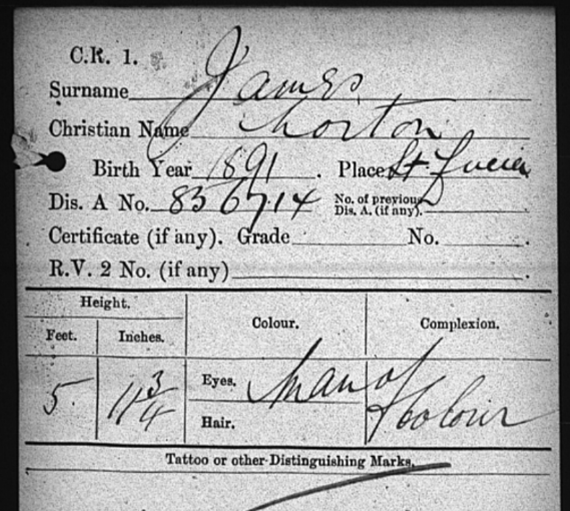

She was the second child of Norton James, a merchant navy fireman, (or stoker) and Sara Agnes Battersby. Norton, who was born in 1891 in the Caribbean Island of St Lucia had served in the British Merchant Navy throughout 1914-1919, for which he received the MN medal for War Service.

Norton James’ official MN card stating him to be a “Man of Colour”. (Copyright Find my Past with thanks.)

Domille’s mother, Sara Agnes Battersby was born in 1900, the daughter of Felix Battersby, at Rathfriland, County Down. In the Irish census of 1911, she may have been the servant, Sara, who creatively stated to be “aged 16”, was living at Rathfriland in the household of a family called Sloan. By 1918 when the couple’s first child, called Norton, after his father, was born, Sara was in Cardiff, presumably having left Ireland in hope of a better life elsewhere. Ships frequently crossed the Irish Sea to the Bristol Channel ports and given her daughter’s later escapade it is tempting to think this method of travel ran in the family. Regardless of how she arrived, Sara’s ensuing life as a teenage mother in a strange land, whose partner was at sea, liable to be away for long stretches at a time, cannot have been much of a honeymoon. Her religion, “Roman Catholic” (as described in the census) is confirmed when she and Norton, now residents of Bristol, were married on 16 January 1920 at the Catholic Church of St Nicholas of Tolentino at Lawford’s Gate.

Catholic Church of St Nicholas of Tolentino at Lawford’s Gate

By 1937 they had produced eight more children, one of whom died in infancy. The baptisms of the children, (most of whose first names are delightfully original, a family historian’s dream) may be hidden away in RC records which must wait for another day.

Life appears to have been bleak for Norton and Sara. In 1921, they lived at 14 Gloucester Lane with Norton junior, 3 and Domille aged one; thirty-year-old Norton was out of work. When at sea he was still a fireman, his last ship named as “SS Polestream”.[1] Without casting aspersions, Gloucester Lane, not to be confused with Gloucester Road, was a miserable place, according to my mother, who briefly lived there when, not long orphaned, she first came to Bristol, aged 10, in 1916.

Sara would have had a proud day 18 November 1932 when the Western Daily Press announced the results of Bristol Eisteddfod. Two of her daughters, Domille and Maura, were amongst the top award winners for Elocution, each receiving 77 marks.

By 1939 with war imminent, the population was counted so everyone could be issued with identity cards. The James family, some old enough to work, then lived at 54 Wallingford Road, Knowle. Norton had left the sea and was working ashore as a general labourer; like most married women in the registration Sara was engaged in “domestic duties”. Norton junior was a market gardener, Domille, an assistant cook, her sister Maura, a laundry packer. The others were either still at school or un-named in published form due to the 100-year rule of privacy.

So far, apart from the girls’ Eisteddfod success, the family had kept completely out of public view, their only mark in standard records. Law abiding, poor but honest.

Life changed for everybody when war was declared in 1939. By the end of 1942, American soldiers, ‘GIs’ were a familiar sight on Bristol streets. Some of these US soldiers were black. At the time, the black and mixed-race population of Bristol was small, and it may have been the first time Domille had met people in any number with whom she could identify. Though there had always been casual racism in the city as elsewhere, Bristolians had not encountered official segregation, black from white, before, and it seems that most citizens were taken aback that our Allies, fighting with us against Nazi oppression, should separate their own men from each other on racial grounds. Perhaps those who thought otherwise kept quiet, not wishing to invite the public ignominy heaped upon Mrs Annie May, the wife of the vicar of Worle in Somerset, who drew up an infamous “six-point plan” in which she advised female parishioners how to deal with the situation if any of these “coloured troops” came to the village.

If one came into a local shop, she said, the woman behind the counter should serve him quickly, but make it plain that he would not be welcome a second time. If a black soldier was in front of a customer in the queue she should go to the back. If one approached a woman on the pavement, she should cross to the other side; if he sat next to her in the cinema she should move away to another seat, and so on. She delivered her advice at a women’s meeting, clearly not expecting the likely result, that one or two might go home and tell their husbands. One of the husbands turned out to be a local councillor. Mrs May found herself the subject of the national news, in a truly cringeworthy story in the Sunday Pictorial of 6 September 1942, under the headline “Vicar’s Wife Insults Our Allies!” in which her ‘plan’ was numbered in detail.

One “Disgusted” Woman spoke to the reporter:

“Any coloured soldier may rest assured that there is no colour bar in this country and that he is as welcome as any other Allied soldier.

“He will find that the vast majority of people here have nothing but repugnance for the narrow-minded prejudices expressed by the vicar’s wife.”

Perhaps Mrs May was lucky after all. The affair does not seem to have been taken up by the local press.[2] Maybe she had rarely, if ever, seen a black person, man or woman, outside the make-believe of the picture house.

One of the very worst things that could happen to you, again according to my dear late Mum (and Mrs May would have agreed), was “getting your name into the papers” as it usually meant trouble. Quite so. And so it was for Domille.

A reporter from a national newspaper, picked up a whisper, and obtained a scoop. He cornered Domille’s sister who probably regretted every word she spilled to him. On 17 October 1943, the eye-catching headline appeared.

TORPEDO FOILS LOVE TRIP”

“Wearing men’s clothes and with her hair up, a 23-year-old Bristol girl outwitted a strong cordon of Police at a Western county dock and boarded a ship bound for America because she could not resist the call of the Negro blood in her veins. But for a torpedo which sank the ship she may now have been in Harlem, New York.

“This girl, whose escape from England in wartime has startled the authorities is Domille James. Her home is at Hampton Park, Bristol. Her mother is British, but her father came from the West Indies forty years ago as a stowaway. Even as a child she was never happy among white children.

“She and her younger sister Eileen determined to go and live with their own people – the coloured people – after the war. Then came Pearl Harbour and America entered the war on the side of the Allies. American troops came here and among them were negroes.

“Domille and Eileen were happy.

“Early in September Domille met a 41-year-old Petty Officer. They fell in love. And here is the story of the adventure as Eileen James told it to me. ‘Domille came to me one Sunday evening and told me she was sailing the next day. I pleaded and argued with her, but she was firm. That was the last we knew until the police told us the ship had been sunk and she was in a Canadian hospital’.

“Domille had planned everything – except the torpedo. But now, as soon as she is well, she will be on the way home.”

And so Domille crossed the Atlantic again, back the way she had come, still a dangerous, though this time an uneventful journey, with the outcome an appearance in Bristol magistrates’ court. The Western Daily Press, 18 November 1943, was one of many reports. If not quite as racy, it was colourful enough,

SIX HOURS in a LIFEBOAT in MID-ATLANTIC: Girl Stowaway’s Adventures”

according to which Domille, of 13 Oxford Street, Kingsdown, had “developed a friendship with an American seaman who had suggested to her that she should go with him to America with him on his ship.” She was secreted first in a store cupboard and afterwards in his cabin. The ship was torpedoed, and she spent six hours in a lifeboat in the Atlantic before being rescued and taken to Halifax, Nova Scotia. She remained there five weeks until deported back to Bristol. She pleaded guilty to the charge of leaving the country without permission of the Immigration authorities. She was bound over to be of good behaviour. Domille promised “I will never do anything so foolish again.” When the verdict was pronounced her mother collapsed and had to be carried from court.

The ship, not mentioned in any of the sundry newspaper reports, may have been the US cargo ship Yorkmar torpedoed and sunk in the Atlantic on the 9 October 1943, 880 km south of Iceland. Thirteen of the sixty-seven people on board lost their lives. The survivors were rescued separately by HMS Duckworth, and the Royal Canadian Ship Kamloops. If my supposition is correct and in view of Domille’s destination, she is likely to have been picked up by the Canadian vessel. The boyfriend’s name is never mentioned. It is unknown if he was among those saved and if so, what disciplinary charges he faced.

11 August 1944, here we go again, report by the WDP. Not quite as dramatic this time.

“We have too much trouble on our streets at night caused by people like you,” Mr H.C. Robbins, chairman of the Bristol Bench, admonished the defendant, Domille James.

With the invasion of Europe the previous month, most of the GIs had been posted, but Domille was seen by a WPC on the Portway, after midnight with one of the few American soldiers still in the city. It was the usual procedure for the Police to ask for an identity card if white girls were seen out after dark with black men. The city which had welcomed black GIs was uneasy about inter-race relations. We have no way of knowing if her current beau was black or white, but it would be beautiful irony if this time the boot was on the other foot! Domille refused to show her identity card and was arrested. She had been in court twice already for the same offence, apart from still being “on probation for leaving the country without permission.” Despite everything, Mr Robbins decided on leniency. She was fined £2, with a grim warning that this was her last chance; the next time she would go to prison. On hearing this, “her mother became hysterical and had to be carried from the court.” Which had obviously become a habit.

Domille remained determined and in the final months of 1945 she was married – to an American soldier. Perhaps William Perry was the same GI with whom she had been canoodling on the Portway. We next hear of her at Southampton as GI Bride ‘USB 1088’, British, address 221 Stapleton Road, Bristol, on the passenger list of the ship Henry Gibbons awaiting sailing on 30 July 1946. She is listed as “the dependent of Private First Class William Perry, ASN 32279503 US Army, of 2413 North 24th Street, Pennsylvania. USA. Efforts to trace Domille’s life in USA have so far been unsuccessful. Her exploits must surely have gone down as legends in the annals of her Bristol family. If you are a descendant of one of her siblings, please let me know. Her brother, Norton James junior was married in 1939 to Venus B.D. Alford. They appear to have had children, Margaret & Peter. Norton died young, aged 31 in 1949. Norton James senior died in 1950 aged 59.

Endpiece

I thought when I began this piece that Domille was unique. However, I found Elizabeth Drewry of Derbyshire (Daily Mirror 25.11.1943) a white girl, who stowed away on a British air-transport plane to Canada. Unlike Domille, she was allowed to stay in Ottawa for a probationary period of 6 months. She was working for the RAF as a ground mechanic and said she wanted to take flying lessons.

Footnotes

[1] Ship’s name unidentified. Palestrina? Palestine? Polestar?

[2] Mrs May best forgotten? “Timeline of Worle 1940-2022” (Worle History Website) has a gap between 1940 & 1943 when apparently nothing happened in the village.

Leave a Comment