On 12th May 1850 when a baby girl was baptised at a small village in Somerset called Queen Charlton, her first name may have caused a slight flutter of interest, as it did to me, more than a century later when I came across her while researching my family history.

The name Pamela was not as rare as the proverbial hens’ teeth, but at the time of the christening it was sufficiently unusual to stand out among the rival throng of Marys, Janes, Elizabeths and Sarahs. Pamela’s parents, Henry, a labourer, and Martha Pillinger, came to Queen Charlton from nearby Brislington, where a Pillinger dynasty had been settled since 1730, and where their previous children, all sons, were born: William, known as George, John Britton, (after his mother’s maiden name), Frederick, Albert, and, in 1841, the fifth, with style, called Fingal, which suggests a nod to Mendelssohn’s Hebridean Overture. Perhaps both parents enjoyed a good tune, (no gramophones then, costly sheet music, Henry playing in the village band?) It may have been Martha who bent towards literature when naming their daughter, a surprise package, born ten years after the previous child, when as a family of three, Henry, Martha and Fingal had moved to Queen Charlton. Pamela, listed precisely, as 11 months old, appears on the 1851 census.

Pamela, as a first or “Christian” name was the invention of the 16th century Elizabethan poet Philip Sidney whose verse suggests it was rendered orally as ‘Pam-ee-la’. It did not come to prominence again until 1740 when Samuel Richardson published “Pamela”, a scandalous two-part novel. The eponymous heroine, an innocent maidservant, fifteen years old, was subjected to repeated sexual assaults by her rich employer, who when seduction failed, abducted her. In Part 2, the boss at last sees the error of his wicked ways, true love prevails and virtue intact, the pair are married.

Whilst this brings about an unlikely “happy ending” for the fictional Pamela there is nothing new about “Me too”. In this context I began to think of the many thousands of working-class women, some as young as twelve, who for hundreds of years were placed “in service”, far from home, perhaps afraid to refuse such advances for fear of being cast out without “a character” or made pregnant and thrown out anyway. Or those 19th century “Home Children”, found situations by those who professionally “cared” for them, and seemingly saw little for alarm in placing young girls in strange households where everyone was assumed to be “respectable”. Living under a stranger’s roof with no chance of escape puts one in a uniquely vulnerable position. Thanks be to the astute official who had second thoughts about a girl called Sarah Ann Childs, who she brought back to the Home in Bristol from Haverfordwest after a year, her “place of service not suitable”. The explanation is not explicit and it is a lone example, but one is bound to the conclusion that a grave mistake had been made.

Some children were sent far away to Canada and Australia.

Not everyone suffered of course. Mary Leighton, (“A Victorian Girl”) adored Mrs Hardy, who she revered as “My Mistress” long after she had left her “place”, though like others, even she had her past history stolen from her

Most sufferers, due to the shame of events which occurred outside their control, probably kept quiet. Their stories are rarely revealed.

I am pleased to say none of this horror was the lot of my ancestral Pamela, though I did worry if it might be the case, when she seemed to disappear off the radar for about 14 years of her life. All was revealed at a later date, but as she had unwittingly become my muse for this ramble down a literary lane, I have chosen to leave it in.

Pamela first came over my parapet in the 1980s, the years of my most zealous pursuit of the Pillinger family history, when I could hardly keep up with them. (No internet in those days, and I compiled a card index, by hand, using old Christmas cards, and wrote it up in slack periods, front of house, during the weird few years we had a family restaurant. The catering trade is war without the absolute carnage, 80% boredom, 20% terror and chaos, though some blood may be spilt too. I cannot deal with boredom and the many strands of the Pillinger family provided a handy sanctuary.)

I placed Pamela, who was not my immediate kin, without paying her too much attention apart from indexing among family, the “Brislington branch” while noting she herself was born elsewhere. Much later, I found her marriage which took place in Bristol in 1877. Her bridegroom was a Charles Walter Cumberbatch. I was vaguely aware at that time that the Cumberbatch family were quite well known in business circles, but that was about the extent of it. My first thought was that Pamela, this daughter of a farm labourer, had gone up in the world by marrying someone posh![1]

As more census information gradually became available, I met Pamela Pillinger again, this time in 1861, aged 10, at Queen Charlton, with her father Henry, shown as “a gardener, domestic service”, and mother, Martha. [2] Just a few months later, in September, Henry died, aged 55. He lies buried in the village churchyard. It is likely that Pamela’s elder brothers, by then variously scattered about, attended the funeral, including Fingal who would have arrived from London. He had been apprenticed as a portmanteau maker and was living in lodgings at St Pancras. Later he returned to Bristol where he carried on his trade, though Bristol Directories, 1886-88 reveal he had grown into his name, possibly his true vocation, as “a Professor of Music”.

I continued to pursue Pillingers wherever I found them, but became increasingly aware that in my travails, I had made the mistake of most newbie family historians, trying “to get as far back as possible”. Prior to the Civil War and Interregnum of the mid-1600s they petered out, and became isolated individuals spotted here and there, so making a coherent family tree became more and more difficult. Having eventually exhausted the supply, mostly males, mea culpa, I began “writing up” what I already had This required putting flesh on the bones, including the women, wives, daughters and daughters-in-law, so often out of sight and therefore ignored.

Benedict Cumberbatch, the actor, came to full prominence with his portrayal of Stephen Hawking in the biographical film of 2008, which I went to see, largely out of scientific interest. Then came “Sherlock”, BAFTAs, and world fame. Bristol & Slavery was by then full on. The star spoke publicly about his descent from his Bristol-born slave-owning family, describing his depiction of the abolitionist Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger in the film Amazing Grace as a “sort of apology”. His fifth great-grandfather, Abraham Cumberbatch (1726-1785) founded the family’s fortunes on a sugar plantation in Barbados. They owned slaves, and in addition to the main line of descent “many people with the surname Cumberbatch living today have kept the name of the family who had owned them.” [as told by Wikipedia]

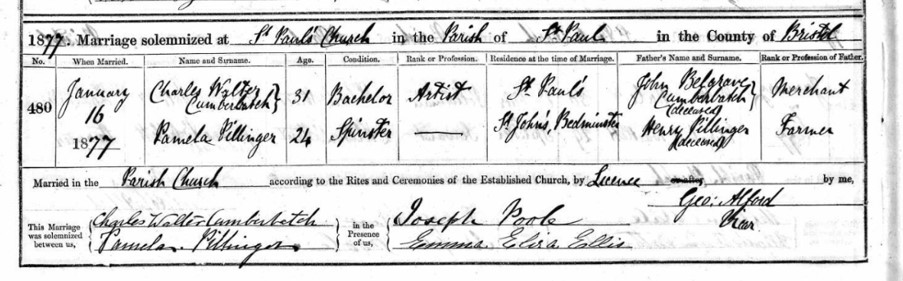

It was a natural progression for me to turn back to Pamela and her husband. Their wedding took place in the parish of St Paul’s, Bristol on 16th January 1877. Pamela Pillinger, “of St John’s, Bedminster, father, Henry, deceased, farmer”, (upgraded for the occasion) was the bride of Charles Walter Cumberbatch, an artist, five years her senior, of Portland Square.

In 2018 I wrote an article which appeared the Bristol & Avon FHS’s Journal no.173, without referring to the glitch which had irked me for some time. After they appeared in the census of 1861 Martha Pillinger and her daughter had gone missing. I had nothing for them between Henry’s burial in 1865 and Pamela’s marriage in 1877 to a man “above her station”.

This mystery was still unsolved when I began this current article in July 2023. If you take up this hobby, beware you are likely to be in it for the long game. Oh, the wonder of internet search engines! I had another go. It took a bit of time, about 45 minutes or so, hardly comparable to the long days out, the bus and train journeys I once needed to search for the merest wisp of information about my ancestors!

In 1871, Martha Pillinger, a widow, aged 64, was the keeper of a lodging house in London, at no. 6, New Ormonde Street, St Andrew’s, Holborn. The second person on the list was her son George. (I knew George of old, but had only met him during his infancy (card index!) when an adamant Martha went to the vestry at St Luke’s, Brislington, and swore an affidavit saying that he had been mistakenly christened William but should have been George, was George now, and ever would be known as George. Why it mattered in those days when he was unlikely to need a passport, I cannot say. I had not caught sight of this baby again, and wrongly assumed his death in infancy, but here he was, still alive, in 1871, in London, a single man of 41, described as a house agent. Next in line was his sister Pamela, aged 20, but shown as “Ella”. How the revelation of a family nickname changes one’s perception of another person! All three had been born in Somerset. The rest of the household comprised an eclectic bunch of lodgers, John Gaunt Stuart, 25, a Scottish bank clerk, Alexander McBride, 39, a surgeon, RN, proudly “on the active list”, born in Ireland, and two Russians, an engineer, Markovitz Lax (or Sax? Or the other way round?), 26, and George Levenson, 24, of no stated occupation. There was also a visitor, Sarah Miles, a spinster lady aged 41, from Yorkshire.

Then…..who do you think in 1871 was living just a few streets away in the same parish in Holborn? Charles W. Cumberbatch aged 25! He was studying law, a student “at the bar” – a profession which did not, it appears, last long. He occupied a single room at 14 Great James Street. He gave his birthplace as Barbados.

At this point I felt like breaking into song, “Sunday in the Park with George”. I still do.

I envisage Charles out walking, when he spotted George, a bit of a swell, who he knew from the letting agency, who was strolling along with a young lady on his arm. He shook hands with the man and tipped his hat to the lady, who George introduced as Ella, not his girlfriend, but his sister. What luck! They would meet again.

If this is not what happened, then it ought to have been. (Like one of my writer-heroes, Nora Ephron, I make a story out of everything!)

More likely Charles met George in the agency and directed him to a vacancy at his old Mum’s lodging house, but I prefer my version. Whichever way, George must have been pivotal in the meeting of working class, though literate, Pamela and Charles Walter Cumberbatch, a former law student, and artist, of a superior social class, but, as it turned out, of mixed race. You cannot help but be drawn into the contradictions of their union.

After their marriage C.W., who was more usually known as Walter,[3] and Pamela (Ella) appear to have moved in with Martha, now back in Queen Charlton. Three of their four children, Lilian Elizabeth, sons Elkin Percy and Charles Belgrave were born in the parish. They lived with Martha until her death aged 79 in 1886 when they departed for Burnet where their last child Alice Beatrice Mary was born in 1888. Their younger son, Charles Belgrave, died aged six, on 25th March 1891, in London, but is buried at Queen Charlton in the same grave as his granny, Martha.

On 5th April 1891, C.W., Pamela and their surviving children were staying at 6 Pelham Place, St Mary in the Castle, Hastings. It is thought they were there temporarily whilst trying to come to terms with grief for the loss of little Charles Belgrave. He had been laid to rest only the previous week.

In 1901 they were in London at 21 Queen Street, Hammersmith, with Elkin aged 20, Alice,12, and one servant. Their elder daughter Lilian had left home having married George William Simpson Willins, a man of independent means, in 1900. The Willins may still been on an extended honeymoon in 1901, but in 1911 they lived in Ealing with their son, George, (Cumberbatch was his third Christian name), two daughters and five servants. Meanwhile, C.W., then aged 65, also “of independent means” and Pamela, were nearby at 79 Madeley Road, also in Ealing. Elkin, 30, who went on to have a distinguished career in medicine, and had lately qualified, was described as “a medical man”; Alice, who never married was aged 22. They employed one servant, a twenty-two-year-old cook, which doesn’t quite suggest the same level of affluence as enjoyed by their daughter and son-in-law, but nevertheless, they were not poor.

Charles died on 31st October 1920 leaving nearly £16,500 and is buried in the churchyard of Holy Trinity Brompton, Kensington. Pamela spent her later life at Cromer in Norfolk where she died on 31st March 1944 aged 95, having outlived her son, but survived by her two daughters, Lilian Willins and Alice Cumberbatch.

Department of Coincidental Footnotes:

Department of Coincidental Footnotes:

THE NAME’S THE SAME. Pamela Cumberbatch described as “Veteran Netball Administrator” appointed Technical Delegate for the Commonwealth Youth Games, 4th-11 August 2023. (I saw this item just as I was tweaking this article, on the same day, 4.8.23!)

For Part 2, of this story, the action shifts away from Pamela to her husband, CharIes Walter Cumberbatch to his birthplace Barbados, and his ancestry.

Footnotes

[1] Like most Bristolians, I was aware of Bristol & Slavery, but at that time, it was not talked about at all, and if you can believe it, there were few references in the catalogues!

[2] Beware: their surname is indexed incorrectly in FindMyPast as “Killinger”.

[3] He was christened Walter in Barbados, and sometimes signed C. Walter Cumberbatch. His family believe he was usually known as Walter. (thanks to Ancestry UK)

Leave a Comment