With Rich Daniels at the entrance to Hopewell Colliery.

On 27 July 2022, my son Kevin took me for a grand day out to celebrate my 85th birthday. The venue chosen was the Hopewell Colliery at Coleford in the Forest of Dean. We had pre-booked our tickets for 12 noon and with only five people on the tour, Kevin and I, plus three generations of one family, were taken to the lamp room where we were kitted out with lamps and safety helmets. We were treated to a brief description of the unique tradition of ‘free mining’ which allows a person born in the Hundred of St Briavels who has worked for a year and a day in a local mine to work a claim or ‘gale‘, in the Forest to mine coal, iron ore, ochre and stone. (Note the word ‘person’. Until 2010 freemining was restricted to men only, then a woman, Elaine Morman, became the first female Freeminer. She successfully lobbied under the Sex Discrimination Act and exercised her right to use the title, fitting the criteria by birth and having worked at her father’s ochre mine for years.) The tour was under the leadership of Rich Daniels, himself a Freeminer, a jovial sort, wearing the full gear, with a pepper and salt beard, neatly finished off with a curly ringlet.

The publicity leaflet for Hopewell Colliery advises that the tour is ‘not suitable for those with limited mobility’: perhaps if I had ‘fessed up’ beforehand, my age and partial sightedness may have been against me, but nobody said anything, so we set off, lit by the dim beam of our lamps, down the steep incline, in single file, Rich at the front, the young woman, the eight year old girl, and then me, sandwiched between the other man and Kevin. I took my time, gingerly choosing each step. It was wet in parts, making me aware that one slip and I would take the whole lot of us to the bottom,, reminiscent of Edward Whymper and his party on the Matterhorn……

The publicity leaflet for Hopewell Colliery advises that the tour is ‘not suitable for those with limited mobility’: perhaps if I had ‘fessed up’ beforehand, my age and partial sightedness may have been against me, but nobody said anything, so we set off, lit by the dim beam of our lamps, down the steep incline, in single file, Rich at the front, the young woman, the eight year old girl, and then me, sandwiched between the other man and Kevin. I took my time, gingerly choosing each step. It was wet in parts, making me aware that one slip and I would take the whole lot of us to the bottom,, reminiscent of Edward Whymper and his party on the Matterhorn……

(I have been known to exaggerate.)

……… with perhaps only my son surviving to view the carnage.

It doesn’t look that steep but believe me it was!

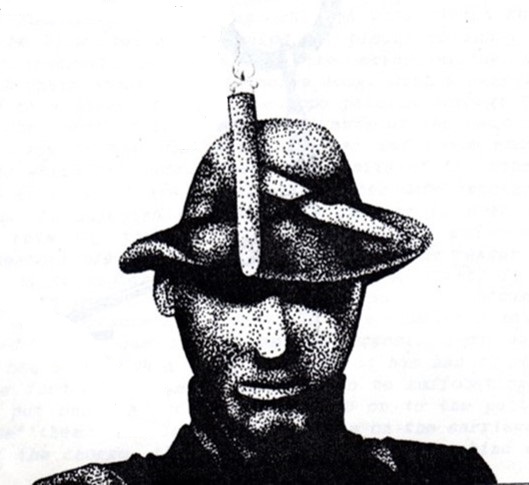

The incline takes you into the heart of the mine, through the different levels dug by the miners of old held up and made safe by sturdy larch wood timbering. Rich explained that very few miners – the hewers, the elite, actually mined, lying uncomfortably full length along the face to hack out the coal from above. The rest of the hands were labourers, repairers, carpenters, trammers, young boys who pushed and pulled loads underground, on rails, harnessed, their shoulders and backs raw until they got used to the heavy loads. Before lamps were introduced, the Forest miners, lit their way with candles, the holders clamped in their mouths.

I shudder to imagine the state of their teeth. Our South Gloucestershire chaps of course had T-shaped iron candlesticks, worn in their hats, which they then stuck in the wall. “Every country do like his own way best” a no-nonsense ‘Kingswood’ miner told the Government Inspector in 1841.

I shudder to imagine the state of their teeth. Our South Gloucestershire chaps of course had T-shaped iron candlesticks, worn in their hats, which they then stuck in the wall. “Every country do like his own way best” a no-nonsense ‘Kingswood’ miner told the Government Inspector in 1841.

Unlike in the Northern coalfields, no women worked underground in the Forest of Dean (or in our local districts, Kingswood, Bedminster and Mendip either). Rich told the little girl in the party that if she had been a boy, she would have been offered a job; in fact might already have been working for a year or two, to her horror and disbelief[1]

The non-employment of females underground was not due to discrimination, as some women would have been capable, hence the fierce and mouthy coal drivers, but due to propriety, because the miners worked naked underground. Clothes would otherwise become sodden with sweat, or through the running water, and with nothing to change into nobody would want to walk home, perhaps several miles, dripping wet.

The signals for raising and lowering were primitive, one pull or two, with the concentration of the engineer crucial as mistakes could easily occur, especially if he left his post for even a second in charge of someone less experienced. I told the company about ‘one of ours’, Isachar Dando, the engineer at Coalpit Heath in 1853 who was told of a pig somebody had purchased at Westerleigh Fair. Excited and desperate to see the animal, he dashed off, leaving his young nephew in control. The confused youngster signalled ‘up’ instead of ‘down’ and a man was ‘precipitated’ skyward out of the pit and was killed. Dando was charged with manslaughter[2]

Hopewell Colliery – What it was like back in the day.

Rich next lit a candle to test the atmosphere to see if there was ‘blackdamp’, at the spot. This is a mixture of gases, carbon dioxide, oxygen and nitrogen in abnormal proportions. If present, the light from the candle or the wick in a safety lamp would have been extinguished. The miner would need to get out quickly before he lost consciousness, soon followed by death. In order to test for blackdamp a canary was famously used as a ‘guinea pig’. If the poor creature fell off its perch unconscious, then it was time to evacuate without delay. This led to a discussion in our party concerning the secondary job of someone needing to look after the canaries above ground. A whole row of tiny cages with chirping small birds flashed into my mind, plus the seeming contradiction of these tough, manly men handling the small fragile birds, even becoming bird-fanciers, as it seemed some did, though many more kept racing pigeons as a hobby.

The other lethal substance below ground is ‘fire damp’, otherwise methane, which causes explosions. Methane, CH4, is lighter than air, burns with a blue flame and has an explosive range 5 to 15%, most violent at 9.4%. It cannot burn above 15% because of insufficient oxygen in the air. The smallest amount detected on the flame of an oil lamp is 1¼% at which all machinery must be switched off and at 2% the hands evacuated to a place of safety. The residue of gas left behind is Choke damp which is another name for Blackdamp, also known as ‘Stythe’, a word I had never heard before, again leading to extinction of candles, and then life itself.

Rich’s lighted candle had not gone out, which showed we were safe. In a ‘gassy’ pit we could have been searched beforehand for matches and lighters which were banned in mines, certainly following the introduction of safety helmets, and nowadays we might be told to leave cameras, watches, mobiles and even hearing aids with batteries behind. I knew that old miners called gas ‘the damp of the earth’. Rich provided an explanation. A German visitor told him that ‘dampf’ was the German word for vapour, which possibly explains how it came to mean ‘gas’. It reminded me how much of our guttural local dialect owes to German, or at least Anglo-Saxon.

Rich then asked the young girl to blow out the candle to illustrate the terror involved if a man’s flame was extinguished in a sudden gush of wind. We were told to switch off the lights in our helmets and were suddenly plunged into absolute blackness. If you have never experienced such dark before, the total lack of light is impossible to imagine and very disorientating. The child took it in her stride but the mother was definitely uneasy, experiencing momentary claustrophobia and was relieved when we were told to switch on our lights again.

The ropes used in the mine were reinforced with steel wire but often became frayed from over-use. Doing ‘a bit of research’ at home later, I came across a case in 1890, when James Rosser, the proprietor of Hopewell Colliery, was summoned for the manslaughter of Isaac Jones, killed by ‘the breaking of the rope’[3]. In another accident at Hopewell in 1869 James Thomas was killed in that most familiar of accidents, ‘the fall of a large coal’. William Jones, his partner, explained “We cannot see the fault until the coal has fallen”. He told the inquest that Thomas said “I will get a bit of coal up this other way,” and began work by saying “I’ll do a bit off this side.” In about a minute, the large piece of coal fell on his head. Thomas spoke once, saying “Oh dear, Jones,” But before they could get him out, he was dead[4]. Both these sad events refer to ‘Hopewell Colliery’ at Coleford, though other newspaper accounts show collieries named Hopewell Drift and Hopewell Engine. I cannot tell whether these are the same pit, two different pits, or even the pit of our day out which had been worked since about 1830. Rich Daniels has since told me there were many pits in the Forest under the name ‘Hopewell’, not surprising, as it signified optimism, and we seem also to have once had one of our own; the name, snatched from antiquity, survives in the street name, Hopewell Hill, in Kingswood, a stone’s throw from where I lived as a kid.

The small Forest of Dean ‘gales’ do not seem to have been very profitable. Theophilus Cooper, a local man, probably a Freeminer, sometime owner of Hopewell Drift, told his bankruptcy hearing in 1897 that the mine had not paid for two years due to the low price of coal; it used to fetch 4/6d to 5/- a ton, but now only 2s 4d. The average output was 4,000 tons per annum and by opening a new level between the previous August and February, 578 tons[5]. His deficiency of £311 was left in hands of the Official Receiver in Newport, while he and his wife and children left the area for Yorkshire, where Theo became secretary to a local Colliery at Keighley, one of those frequent migrations of colliery people from one district to another.

Down the pan – the coal slide

We had by this time paused beside a loaded ‘tram’ from which the eight year old was allowed to take a souvenir knob of coal. Above us was a seam where miners had hacked out coal, back filling the spoil as they went, before sending the mined coal ‘down the pan’, a flat chute, into the tram. Rich said this expression originated with mining. (“Down the pan again”, my Dad, an unlucky gambler, would always say when his ‘oss’ or dog had lost. As he came from a long line of miners, who knows?)

Our outward journey ended here, with above us a level where the hewers worked. To climb up to it would have proved a challenge, certainly for me, and it did not form part of our current tour, though I understand it would be available in a longer version with prior arrangement. Such a party would then “exit the workings by the beautifully engineered old furnace erected in the 1820s..[then] follow the old tram road through the tranquillity of the Forest back to the museum and shop.”

We exited by climbing up the same incline into the outside world and a welcome lunch at the excellent café which houses a small museum.

Also in the vicinity of Hopewell Colliery is the Sculpture Trail, with a highlight, ‘the stained glass window’; the scenic viewpoint over the river at Simmonds Yat, and the Speech House, the historic 17th century senate building where mining problems and complaints were thrashed out in former times. The Speech House, now a hotel, which occupies a special place in Lindegaard family history: we spent our honeymoon night there!

Note: These are my impressions of the day. As a lay person, I do not pretend to any expertise about the Forest of Dean mines. For more information about Hopewell Colliery and mining in the Forest of Dean consult the definitive website. The website is enormous and comprehensive, but fairly complicated. Dave Tuffley, in whom I recognise a kindred spirit, has collected over 700 fatalities and these can be found within the above site. Due to age and technological ineptitude, (I probably need to engage the help of a ten year old child) speaking personally, I would welcome a straightforward, easily accessible alphabetical index of names as in my own KIACP. Bring back books!

I also recommend the glossary of mining terms from which the information on various ‘damps has been gleaned.

Notes and References

[1] About 40 years ago, I used Kevin, then aged about 7 or 8, as an exhibit, a child miner, one of his own ancestors, when giving talks about Kingswood coalmines.

[2] ‘Killed in a Coalpit’, D.P.Lindegaard.

[3] Western Daily Press 9.5.1890

[4] Stroud Journal, 5.6.1869

[5] Glos Journal, 24.2 1897, Glos. Citizen, 28.4.1897.

Blog Comments

Jackie Friel

25th August 2022 at 10:47 am

An interesting, well-informed article. I can’t begin to imagine how it felt to live half my life underground in such a hazardous environment.