In the present year, 2022, Amelia is number 3 in the top one-hundred girls’ names.

Before we get to Amelia Pillinger let’s start with…two historical Amelias:

The name first became popular when the German born Princess Amelia, 1711-86, daughter of the future George II and Caroline of Ansbach arrived in England when her father became heir to the throne. She never married but was the patron of the young Samuel Arnold, afterwards a prolific and successful composer. According to his memorial in Westminster Abbey his birthdate was 10 August, 1740, though no baptismal record has been found for him. Many unproven sources state that Amelia was his mother through an association with a commoner, Thomas Arnold.[1]

The name first became popular when the German born Princess Amelia, 1711-86, daughter of the future George II and Caroline of Ansbach arrived in England when her father became heir to the throne. She never married but was the patron of the young Samuel Arnold, afterwards a prolific and successful composer. According to his memorial in Westminster Abbey his birthdate was 10 August, 1740, though no baptismal record has been found for him. Many unproven sources state that Amelia was his mother through an association with a commoner, Thomas Arnold.[1]

‘Amelia’ continued in favour through the next Princess Amelia, 1783-1810, the youngest of the six daughters of George III and Queen Charlotte. Their parents were reluctant for any of the girls to marry and they mostly lived sheltered lives.[2] Amelia in particular suffered ill-health throughout her life. However, sent to Weymouth for the benefit of sea air, she fell in love with an equerry, Charles Fitzroy, twenty years her senior. She knew she would not be allowed to marry him but told her brother Frederick she considered herself to be his wife and signed with the initials A.F.R. (Amelia Fitzroy). Amelia died of erysipelas aged twenty seven.

‘Amelia’ continued in favour through the next Princess Amelia, 1783-1810, the youngest of the six daughters of George III and Queen Charlotte. Their parents were reluctant for any of the girls to marry and they mostly lived sheltered lives.[2] Amelia in particular suffered ill-health throughout her life. However, sent to Weymouth for the benefit of sea air, she fell in love with an equerry, Charles Fitzroy, twenty years her senior. She knew she would not be allowed to marry him but told her brother Frederick she considered herself to be his wife and signed with the initials A.F.R. (Amelia Fitzroy). Amelia died of erysipelas aged twenty seven.

Birds in gilded cages. It is clearly no joke being a royal princess.

———————————-

The story of ‘my’ Amelia Pillinger begins on 19 March 1870 when the Berkshire Chronicle put out a squib:

‘Mrs Pillinger, the wife of the well-known Bedminster cricketer, on Saturday gave birth to four children, two of whom have since died.’

Other newspapers as far as Perth in Scotland (though not apparently Bristol) found this short news item of sufficient value to reprint it, usually word for word, though the Devizes & Wiltshire Gazette of the 24th March picked up the cricketing analogy; it headed its piece, ‘A Good Score’, but having used this flippant title forbore to mention the tragic loss of two of the infants.

None of the papers thought it necessary to send out a reporter to investigate the multiple birth which was so rare at this time in history that the word for quadruplets had not yet been coined, and even triplets were often reported as ‘three twins’! The cult of minor celebrity did not, of course, exist either and the first names of the parents were not stated. A couple of clues though made identification simple: the father was locally famous as a cricketer who played for Bedminster.

A short search of the sports news for ‘Pillinger’ and ‘cricket’ revealed numerous appearances and occasionally his initial ‘W’. For instance Bristol Mercury 24 March 1870 reported the inauguration of ‘The Carlton & Athletic Club’ of which Mr W. Pillinger was one of the captains with the first annual dinner to be held the following Monday at ‘the Hen & Chickens, a well-known roosting place for cricketers at Bedminster’. (By coincidence, the Hen & Chicken, [now singular], was the local where my grandfather, [Albert ‘Pap’ Pillinger, 1874-1973] held nightly court during the final phase of his life.)

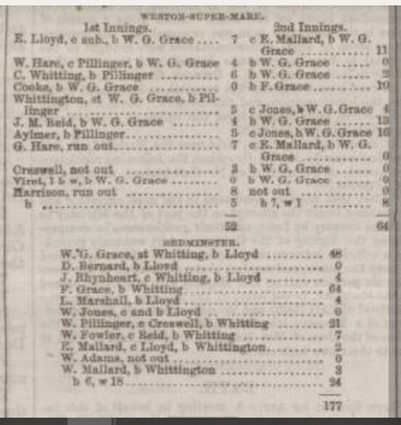

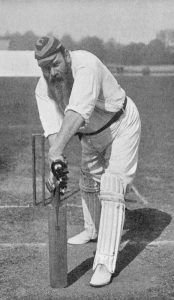

Scoreboard, Western Daily Press 9.7.1866 shows that William Pillinger played in illustrious company ………..

W G Grace ..…….‘the most famous Victorian after Queen Victoria herself.’

Pillinger took three wickets and a catch (off W.G. Grace’s bowling – he would not have dared do otherwise) – and scored 21 runs. Bedminster won by an innings.

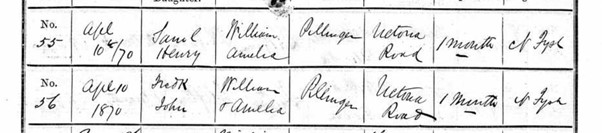

The registration of births for 1870 shows two Pillinger boys, Frederick John and Samuel Henry on the same page of the June quarter. The other babies did not live long enough to be recorded and their tiny corpses must have been buried without ceremony. The two remaining quads were baptised at Hebron Methodist Church, Bedminster on 10th April:

Sadly little Freddie died at three months old and was buried at Hebron on 7 July 1870.

Though this non-conformist register does not supply the occupation of the head of the family I knew that William’s day job was as an officer for HM Customs and Excise.

Though this non-conformist register does not supply the occupation of the head of the family I knew that William’s day job was as an officer for HM Customs and Excise.

In the census of 1871, the family was split into three separate households, Amelia and the remaining quad, Samuel aged one,

Hebron Methodist Church. Bedminster [3]

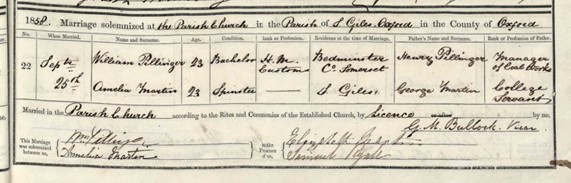

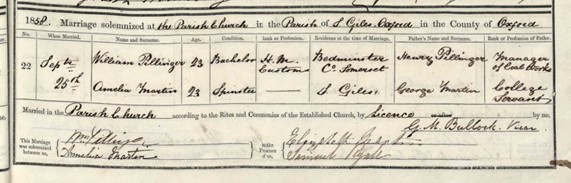

Now that I knew Amelia was born in Oxfordshire, it took a matter of moments to find her marriage to William Pillinger at St Giles, Oxford in September 1858:

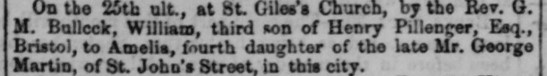

They were grand enough to announce the wedding in the Oxford Chronicle of 9th October: [4]

They were grand enough to announce the wedding in the Oxford Chronicle of 9th October: [4]

How a particular couple managed to meet is usually lost in the mists of time. However William did not wake up one morning and go to work the same day as a fully-fledged Customs and Excise man. There would have been an application, a selection process and with success assured, a probable course to learn the ropes of the job. This may have been why William was in Oxford; there is something about a man in uniform (!) or perhaps he was even playing cricket there? A marriage by ‘licence’ rather than banns (which required three prior Sundays of church attendance) has a whiff of ‘poshness’ but it may simply be that William had to be back at work in Bristol.

How a particular couple managed to meet is usually lost in the mists of time. However William did not wake up one morning and go to work the same day as a fully-fledged Customs and Excise man. There would have been an application, a selection process and with success assured, a probable course to learn the ropes of the job. This may have been why William was in Oxford; there is something about a man in uniform (!) or perhaps he was even playing cricket there? A marriage by ‘licence’ rather than banns (which required three prior Sundays of church attendance) has a whiff of ‘poshness’ but it may simply be that William had to be back at work in Bristol.

Badge of a Victorian Customs’ Officer.

By 1861, the young couple, both aged 25, were living at 2 Prospect Place, Bedminster with a surprise, a daughter, one year old Amelia Catherine. Also part of the household was the widowed Mary Ann Martin, Amelia’s mother, a ‘landed proprietor’, aged 60, born in Yarmouth, Norfolk with her spinster daughter Julia, 27.

Amelia Catherine was baptised at Back Lane Methodist Church, Bedminster on 4 October 1859. The little girl died, tragically on the cusp of young womanhood aged nine and was buried at Hebron on 14 April 1869. The Pillingers had therefore lost four children in quick succession, not only the three babies as I had thought, but an older child too. The latest bereavement must have had a devastating effect, particularly on the mother, and it is no wonder the family was fractured in 1871.

Amelia Martin’s parents did not come originally from Oxford. Her father, George, son of John and Mary, was ‘privately baptised’ (signifying he was not expected to survive) at Yarlington, Somerset in April 1794, though he was born four miles away at Bruton. Amelia’s mother, nee Mary Ann Grist, was born at Great Yarmouth, Norfolk on Christmas Day 1796 and baptised there on New Year’s Day 1797. Her parents were John and Elizabeth, formerly Merchant.

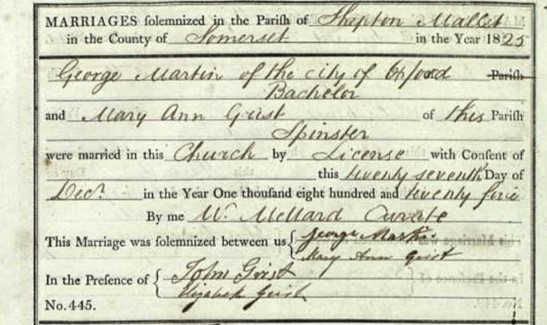

George Martin and Mary Ann Grist were married by licence – George was working in Oxford – on 27 December 1825. The marriage was witnessed by the bride’s parents and all parties concerned signed the register.

As it turned out the Grists, like the Martins, were a Somerset family. John Grist married Elizabeth Merchant at Shepton Mallet in 1794 – but he was already living at Yarmouth when he returned for the wedding: he is described ‘a sojourner’ in the parish register, whilst his bride was ‘of this parish’. In previous centuries, though people roamed it was often in baby steps close to the vicinity of ‘home’, so what was all this gadding about? In the case of Amelia and William Pillinger we can point the finger at the railways but George Martin had gone to Oxford, nearly a hundred miles from Bruton, well before the first passenger train and John Grist to Norfolk, over 260 miles away, almost three times as far! No mean feats when transport was by coach or even by carrier. As it happened John and Elizabeth Grist eventually came back to Shepton Mallet and Amelia possibly spent much of her youth there. Elizabeth died in 1831 aged 58, but John, bless him, survived long enough to be counted at the cack-handed census of 1841 where ages were ‘rounded down to the nearest five years’ which confused everybody. He was stated to be ‘65’, a confectioner, living at the inn at Church Street, Shepton Mallet, with Benjamin Merchant, the innkeeper, probably a relative of his late wife. When he died in March 1847, John Grist was allegedly seventy seven. As I have said before, nobody registers their own death and (even in my youth) it was considered cheeky to ask the age of your elders, so we often get some wild guesses.

But let us follow Mr & Mrs George Martin to Oxford, where George worked as a Common Room Servant at St John’s College. Soon they had a string of children:

George and Elizabeth, were ‘privately baptised’ on 9 March 1827 and received into St Giles’ Church on 6th April. (They were twins, suggesting an inherited tendency for multiple births.)

Mary, baptised as Marianne, on 19 December 1828, address Beaumont Buildings, Magdalen Parish.

Julia Catherine, 7 July 1830, Fairmont Buildings, St Mary Magdalen

William, ‘born 4 July and baptised 5 September 1832, son of George and his wife Mary Anne, late Grist, John Street, Common Room Man at St John’s College’. (If only all vicars were this explicit!)

And at last, Amelia, baptised 15 May 1835, St Giles, Oxford, daughter of George and Mary, College Servant.

I thought that Amelia was the youngest child, a theory seemingly confirmed by the 1841 census which shows George and Mary living at St John Street, parish of St Giles with their children all present and correct as baptised, by then aged 14, (the twins), 12, 10, 7 and six.

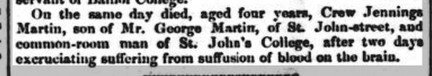

However, a notice in the Oxford University and City Herald 15 May 1841 reveals the little life, and painful death of a seventh child which had taken place the previous Thursday:

Crew Jennings, whose specific first names show he must have been named after someone very important to the family, was baptised at St Giles on 18 August 1837. The census of 6 June 1841 conceals a household in mourning.

Ten years later in 1851 at the next census the twins had left home, either married or working away, with the others still with their parents aged, 22, 20 18, and Amelia herself aged fifteen, a scholar’.

George Martin senior died apparently suddenly, on 3 November 1852 aged 57 at 31 John Street. (There was a terse death notice in the ‘Herald’). He was buried at St Giles on the 9th of the month. An advertisement in the Oxford Journal of 18th December which requested claimants on the estate to come forward suggests there was no will:

William and Amelia Pillinger probably left Oxford shortly after their wedding in 1858 and began their married life in Bristol. Soon they had a baby daughter and on some occasions were visited by Amelia’s mother and sister Julia.

Though there must have been a small amount of prestige attached to William’s job, Customs Officers in a busy seaport were not the most popular of men and they themselves considered themselves undervalued and underpaid. For instance the Western Daily Press, 27 June 1866, reports a meeting of the Outdoor Customs Officers (among whom I assume was William) complaining that since they entered the service their classification had changed resulting in a loss of remuneration. Additionally prospects for promotion were nil except following the death or disgrace of a brother officer. Representations to the Board had been rejected. A petition had been sent to the House of Commons; currently the Government Inspector was in Bristol and a deputation had been formed to present their case to him. As far as I can tell, nothing came of it.

From a report in the Bristol Daily Post, 3rd September 1868, we can ascertain that money was tight. Amelia had to resort to the pawnshop (she needed to pawn a bed) though for the sake of propriety entrusted the transaction to Caroline Iles, probably for a small fee. Iles, assisted by another woman, Ann Howell, carried the bed to ‘uncle’s’, Mr Olive’s pawnshop, on Redcliffe Hill. (It is not hard to picture the pair humping the bed through the streets of Bristol.) Olive’s assistant issued a receipt in exchange for the goods which Iles passed on to Amelia Pillinger. A month later Iles returned to the shop and alleged she had lost the ticket; she swore to the same before a magistrate. On July 10th she obtained the bed out of pledge and sold it to Mrs Davis, the landlady of a tavern in North Street. Iles was charged with perjury. The bed had been ‘returned to Mr Pillinger’, who I suspect was less than pleased that his name had been brought into it, though his occupation and spare time activity had fortunately not been revealed.

In April 1869, Caroline Iles, a 38 year old glovemaker was found guilty of perjury and gaoled for six months with hard labour.

Perhaps it was ‘the shame’ of this case (when people had little they were very protective of their good name) which added to the apparent rift in the marriage still evident in 1871.

The 1881 census was taken on 3rd April, by which time, William, Amelia, both 45, and their children were reunited at 9 Sidney Street, Bedminster. William George, by then 19, was working as a coachsmith; Julia Ann, 16, and Samuel, 10, were both at school. It seems that Amelia was already ailing. She died on Saturday, 10 June 1882.

An inquest at the Spotted Cow in North Street was convened for the following Monday, due to the suddenness of death and perhaps because rumours had been circulating that her husband ill-treated her.

William Pillinger told the court his wife had been ill for months with heart and lung disease. He had wished her to have the Doctor, but she refused. On the previous Tuesday he went to see Dr Logan and told him she was suffering from a slight fever. She took the medicine Logan prescribed and the fever abated. By the time he came home that evening she seemed much better, though she asked him to get some different medicine for her cough as she said he ‘would not otherwise get any sleep that night’. He went to the Doctor again and obtained the linctus. She slept through the night and by Thursday morning said she was ‘much better’. She took a little cornflour and milk and again passed a good night. He left for his duties on the Friday morning and by three ‘clock he was brought news that she was dead.

The Deputy Coroner: “I believe your wife used to drink didn’t she?”

Pillinger: “Yes, sir.”

Deputy Coroner: “A report has been submitted that you neglected her.”

Pillinger: “There is not the slightest truth in that. It was probably circulated by some persons I would not allow to come to my home.”

Annie (Julia) Pillinger, daughter of the deceased: “My mother took the medicine and the food. She seemed much better Friday morning. She would not let father stay at home. My brother stayed with her.”

Ann James, widow, West Street, a neighbour: “At about 11 or 12, the little boy came round to my house to fetch me. By the time I got there, Mrs Pillinger was dead.”

Doctor F.B. Logan: “I have treated the deceased off and on for three years for disease of the lungs, which may have been accelerated by drinking. Mr Pillinger had always appeared anxious about his wife and I do not think there is any truth in the statement that he neglected her. She died from consumption accelerated by drink.”

The Jury delivered a verdict according to the medical evidence and exonerated Mr Pillinger from all blame. He had “done his duty” said a Juryman. The Deputy Coroner said it was shameful that people should put about unfounded tittle-tattle.

William Pillinger married his second wife Martha Pearce in 1883. He was still a Customs Officer in 1899, when they lived at Luckwell Lane, at a house with a large garden. He summonsed a boy found up a tree with his pockets filled with blackcurrants who was fined half a crown. By 1901, by then retired he and Martha were listed at East Street, Bedminster. Julia Ann married Walter George Daniels, a stonemason, in 1893. In 1901 they were at 34 Maidstone Street, with their two children; Julia’s brother Samuel, the last quad, a builder’s labourer, a single man of 31 lived with them. The fate of their elder brother William George is not known.

[1] There is nothing about any love affair in Samuel Arnold’s entry in the Dictionary of National Biography.

[2] This may be understandable considering the horror of the marriage of King George III’s sister, Caroline Mathilde, 1751-75, Queen of Denmark. https://www.google.com/search?q=caroline+mathilde+dictionary+of+national+biography

[3] For the interesting history of this church, see http://www.well-and.co.uk/Welland-p/pi138.htm. The burial ground is notable for the remains of Mary Baker, the impostor, better known as the ‘Princess Caraboo’.

[4]Henry Pillinger, William’s father, was Bailiff, and Moses Stewart, the Manager.at Malago Pit, Bedminster. Following a disaster at the pit in August 1851 when six lives were lost, Stewart and Pillinger were tried for manslaughter and subsequently acquitted. See pages 61-66 in the pdf ‘Pillingers…Part 2’

Read about other pillinger women at the following links:

Leave a Comment