The first in my new series of my Pillinger women ancestors starting with Hephzibah Day Pillinger.

When I began my family tree back in Palaeolithic times like most newbies I was guilty of racing along the male strands of those who bore my family name, PILLINGER to ‘get back’ as far as possible. It was hard enough to find the men, let alone the women, ‘his sisters, his cousins and his aunts’, as Gilbert & Sullivan put it, who shared their lives, so mostly apart from the bare details they were ciphers. But, because ‘Pillinger’ is less common than many other surnames and through the finding aids with which we are now blessed, I decided to set about rectifying the omissions.

Hephzibah Day Pillinger c1805/1808 – is the first subject in this series because a Hephzibah is good news: saving me from sinking under the endless swell of Sarahs, Anns and Janes and also because I knew a bit about her history already.

The original Hephzibah, Hebrew: ‘my delight is in her’, gets a single line in the Bible (2 Kings, 21.1.) As usual for a woman she is identified only by a man in her life, in this case her son, Manasseh, who became King of Judah aged twelve, ‘And his mother’s name was Hephzibah’. Manasseh seems to have been a bit of a wild child, who committed ‘abominations’ in the sight of the Lord, i.e. using ‘enchantments’, conjuring ‘familiar spirits and wizards’. Magic Mushrooms? Whacky Baccy? Does this mean that Queen Hephzibah too was of a doubtful moral character? Unable to control her son? It’s always the mother’s fault.

This happened about 700 years BCE, but it fits in with my theory that nearer our own times parents having used up more everyday names riffled through the Bible to find ‘somebody Biblical’ after whom to name the latest offspring.

The stylised title portrait is nothing like ‘my’ Hephzibah of course and probably nothing like the original either! (acknowledgment with thanks to https://www.womeninthescriptures.com/2017/03/list-of-all-women-in-old-testament.html)

‘My’ Hephzibah was associated with George Pillinger, who was baptised in Corsham, Wiltshire in 1805, but died in Tasmania in 1864, which is a clue to the major upheaval of his life. In his youth George was responsible for a mini crime wave in his village a sheep, a sovereign and a couple of minor ‘assaults’. After several short gaol terms, following by a period going straight, he turned to house breaking, and was charged on 19 November 1834 with the theft of one counterpane, two worsted ‘comforters’,[1] five pairs of gloves, a shawl and a cap, from James Gray of Corsham. George was number 25 on the Court Calendar and lower down on the same roll at number 28 was Hephzibah Pillinger and her daughter, Betsey Day, arrested for the theft of an umbrella. More details of this affair appeared in a later edition of the Salisbury & Winchester Journal of 1 December 1834:

Hepzibah [sic] Day alias Pillinger, aged 26 and Betsey Day, her daughter, aged 9, were charged with stealing an umbrella, the property of Thomas Gibbons of Corsham….…the prisoners went to the shop of Mr Gibbons between 7 and 8 o’clock on the evening of 15th November and after purchasing a number of trifling articles a person who was outside observed the younger prisoner bring an umbrella from the shop and soon afterwards deliver it to her mother. The person then went to the house of the prisoners the following day and heard the younger prisoner say

“Mother it do rain now, hang the umbrella out so that it may get wet, then it won’t be known.”

The mother replied “Never mind, it don’t rain hard enough for it to get wet. I’ll throw some water over it by and bye and that will do.”

The umbrella was found at the house and identified as Gibbons’ property. Hephzibah and Betsey were tried and found guilty. Mr Estcourt (the Magistrate, from a family of Baronets, High Sheriffs &c) reprimanded the mother and sentenced her to six months hard labour and the child to fourteen days in solitary confinement.

I hope Mr Estcourt and especially the busybody nark had sweet dreams.

George Pillinger was convicted on 6 January 1835 and sailed into exile aboard the Bardaster. He arrived in Van Diemen’s Land on 31st August that year.

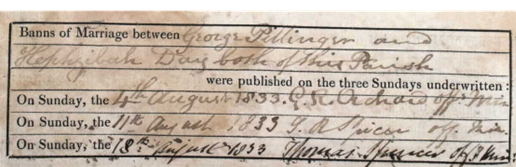

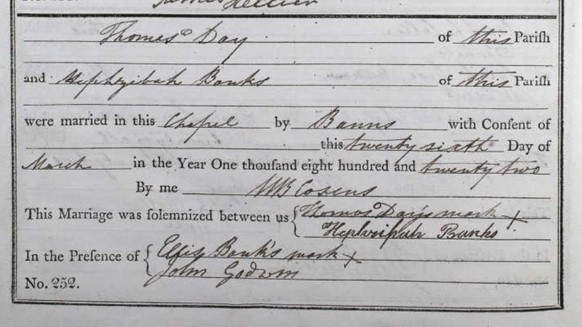

For some time George and Hephzibah had appeared in my records as simply ‘George Pillinger =? Hephzibah —— ?’ Then having plucked up courage to join Ancestry I found they were married, after banns at Westwood with Iford, twin villages, one each side of Iford Manor, near Bradford on Avon.

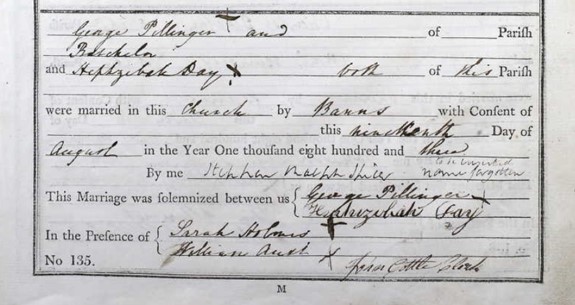

What good fortune that the banns survive! The marriage itself took place on 19 August 1833, though the year is shown as ‘1803’.

George was a bachelor, Hephzibah without status. Despite the proliferation of ‘X’s’ it looks to me that he was illiterate but his bride after hesitating over the first two letters of her name, even possibly changing the quill pen, signed slowly and carefully. The scribbled note on the right of the document states that in addition to the wrong year, which had gone unnoticed, the vicar forgot to include his name and had to return to add it later. Shambles all round.

The two witnesses unfortunately mean nothing to me.

I cannot help but observe that George and Hephzibah had been married just over a year when their cases came up. Perhaps his return to crime was his misguided way of getting a home together.

I thought Betsey must have been ‘a love child’ and that I would then find both her baptism and Hephzibah’s in a matter of minutes. When this did not happen once again the investigation went back to bed for a few years.

I am a magpie when it comes to collecting ‘stuff’. One day during ‘lockdown’ when randomly trolling through newspapers for the 1830s I came upon a short article about inmates who had survived to great ages (for those times) at Clifton Workhouse. (Five stars on TripAdvisor?) One thing led to another and I began looking for the names of these people in the burials of St Andrew’s, Clifton. I was completely floored when, by total serendipity, I noticed an entry for 1839:

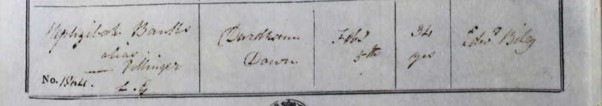

“Hephzibah Banks alias —– Pillinger, Durdham Down, Feb. 5th, 34 yrs.”

(NB: Initials L.G. signify Lower Ground in the churchyard.)

I whooped with joy. So Hephzibah had survived her imprisonment and had made her way to Bristol! Her abode was Durdham Downs, the City’s great green space. Was she living outdoors? A vagrant? Even so, somebody knew her name and guessed her age enough to give the details for the register. It can often be overlooked that no-one records their own death! Few people knew how old they were anyway and though the burial age did not tally with the report of Hephzibah’s imprisonment, it matched exactly the year of George Pillinger’s birth. Was there a ‘Mr Banks’? I supposed him to be Hephzibah’s new partner whose surname she had adopted, but was unable to marry, George being still alive though out of reach. A search for Mr Banks drew a blank but still enthusiastic, I revisited Corsham, not in person as forty years ago, but now online.

There were no Days at Westwood with Iford but plenty at Corsham. No baptism for a Hephzibah though and none for a Betsey or Elizabeth with a mother Hephzibah. I put the first name in the finding box without a surname and more Hephzibahs than you would think tumbled out, but one, at which my head nearly fell off, showed a marriage for a Thomas Day and a Hephzibah Banks in 1822 at Winsley, a village two miles from Bradford-on-Avon.

Once again the groom marked with a cross but the bride signed. Unfortunately the two Hephzibah signatures are different even allowing for the gap of nearly eleven years. At last there was a family witness ‘Ellis Banks’, ‘X’, but I found no Ellis (of course) or one for a misheard ‘Alice’. There is an Elias Banks but nothing emerged apart from his baptism at Biddestone in 1784.

Thomas Day appears to have been the boy of this name baptised at Corsham on 23 December 1799, the son of William and Selina. As yet I have still not found a baptism for Betsey Day.

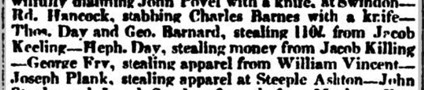

After this I turned again to the friendly newspapers and the first item I found was in Bath Chronicle, 1 November 1827.

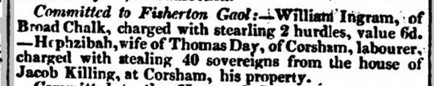

‘Committed to Fisherton Gaol:- William Ingram of Broad Chalk charged with stearling [sic] 2 hurdles, value 6d. Hephzibah wife of Thomas Day of Corsham, labourer, charged with stealing 40 sovereigns from the house of Jacob Killing, at Corsham, his property.’

This was a huge amount of money; for comparison, note the ‘crime’ of William Ingram.

Fisherton, the ‘new’ County Gaol, had opened five years before, part of the movement for Reform. The prisoners no longer milled about the premises as in earlier times but were lodged in separate cells. A chapel was provided for worship, but there was still a treadmill for incorrigibles and public executions took place on the gallows outside. The infamous ‘Bloody Code’ which had included the death sentence for theft was in suspension though not abolished. For an execution to take place the dread words had to be orally transmitted by the judge to the guilty person. If at his discretion he wrote ‘Death recorded’ in the book it meant the opposite, that the thief’s life would be spared. Subsequently he or she would receive a ‘pardon’ on condition of a term of transportation ‘at His Majesty’s pleasure beyond the seas.’[2]

Whether Hephzibah Day was aware of the legal machinations or not, she would still have been terrified. Meanwhile, what had happened to the infant Betsey? Could Hephzibah take her child with her into gaol? Otherwise who looked after the two year old?

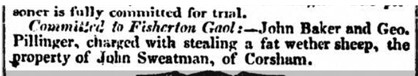

In this tale of coincidence, who do we find already lodged inside Fisherton when Hephzibah arrived? None other than George Pillinger, taking one of his frequent holidays.

On 8 October 1827 the Salisbury & Winchester Journal records:

‘Committed to Fisherton Gaol:- John Baker and Geo. Pillinger, charged with stealing a fat wether sheep, the property of John Sweatman, of Corsham.’

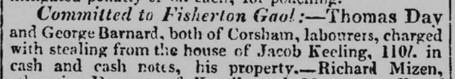

Did he and Hephzibah meet for the first time ‘inside’ or did they already know each other? Shortly afterwards, recorded on 26 November 1827 in the same newspaper, Thomas Day was also arrested with George Barnard for the theft of an even greater sum, £110 in cash and notes from Jacob Keeling, same man, different spelling, and was likewise committed:

George, Tom, and Hephie spent five months in gaol waiting for their cases to come up; their names appear in the crowded calendar of those on trial in S & W. J. again, 10 March 1828.

George Pillinger was found guilty of sheep stealing and awarded three months. Thomas and Hephzibah Day were found not guilty of their far more serious charge.[3] My guess is that it was all a mistake and Keeling found the money. As they were acquitted the press was no longer interested in them and nothing of their trial is reported. Move along now, nothing to see here.

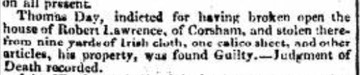

Whilst George continued onwards in his merry bachelor way, the Days lived, as far as I know, a trouble-free life until the winter of 1830-31 when Thomas Day was arrested for burglary at the house of Robert Lawrence of Corsham, and ‘stealing therefrom nine yards of Irish linen, a calico sheet and other articles.’ He was convicted at the Lent Assizes of 1831 before being removed from Fisherton to the York Hulk at Gosport to await transportation for life. I suspect the court was of the opinion that he had escaped justice the previous time hence the harshness of the sentence. As usual on 14 March 1831, the reporter from S. & W. J. was on hand to record the event:

‘Thomas Day, indicted for having broken open the house of Robert Lawrence of Corsham and stolen therefrom nine yards of Irish cloth, one calico sheet and other articles, his property, was found Guilty. – Judgement of Death recorded.’

Note the mandatory ‘death recorded’. In the same Assizes the death sentence was pronounced. ‘The Learned Judge was considerably affected by the delivery.’ Not half as much as the condemned man I would suggest.

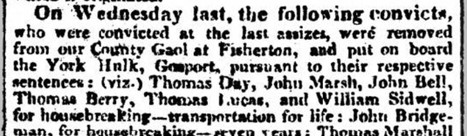

Thomas’s removal is in the newspaper of 16 May 1831:

So both Hephzibah’s men met with a similar fate. Excuse me if I paraphrase the peerless Oscar Wilde:

‘To lose one husband to transportation may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.’

There are plenty of unanswered questions. Was there one Hephzibah or two, with a complicated patchwork of surnames, Banks, Day, Pillinger? With Thomas Day gone forever, and knowing she was committing bigamy was Hephzibah cunning enough to alter her signature when she married George Pillinger in 1833? If neither bride had been literate I would have accepted one person with two marriages without question! Where did she or they receive an education? Where were the missing baptisms? What happened to little Betsey?

These various puzzles beat counting sheep as a cure for insomnia.

Having exhausted all avenues, I did what a less frugal person would have done in the first place, that is, verify the burial by purchasing the death certificate. But by this time I was so thankful that this would be the end of my quest that I failed to notice that the burial was in the March quarter of 1839 and the registration of the death was in the June quarter. But even if I had been more vigilant I would still have sent for the certificate.

And this is the result. Clifton Union, Registrar’s District Ashley, in the City and County of Bristol

Fifth June, 1839, Stokes Croft, St Paul. Hepziba Banks PAUL, girl, aged 11 months, infant, daughter of William Paul, Butler, Cause of Death, Consumption, the Mark of X Maria Paul, the mother, present at the death, 29 Stokes Croft.

Who the Hell was Hepziba Banks Paul, poor little cherub? And who exactly was buried in Clifton on February 5th in 1839 as Hephzibah Banks alias Pillinger?

The famous motto of the Royal Society is Nullius in verba, which roughly translates as ‘Take Nobody’s Word for it.’ It applies equally well to those who put such store by ‘the original register’ which can still be fallible, as well as reminding all of us family historians to ‘Check, check, and check again.’

(A version of this article will also appear in the BAFHS Journal)

References:

[1] Bedding or clothing? A ‘comforter’, a long woollen scarf as worn by Bob Cratchit in lieu of an overcoat, or a sleeping bag made of two blankets sewn together, the preferred definition in the USA.

[2] The eccentric system, which seems to me ‘typically British’, not surprisingly causes confusion. A well-known US author came to grief with ‘death recorded’ not long ago. After her book was published. Ouch.

[3] The record of their acquittal is in England & Wales Criminal Registers, 1791-1892, but is too faint to reproduce.

For more on the Pillinger Family see:

THE PILLINGER FAMILY – PART 1 – “FROM YATTON KEYNELL TO OUTER SPACE”

Leave a Comment