The history of Jimmy Peters, the first black man to play Rugby Union for England, and the sketchy life of his father George is told in a previous blog. In this post, I return to the Peters family’s life in Bristol with a few diversions….

Warning. This account contains words which are offensive and now unacceptable but were in common usage at the time portrayed.

George and Hannah Peters, a mixed race couple, with their children Jimmy aged four and Charlotte, two, had arrived in Bristol by 2 February 1883 when their new baby, Robert was baptised at St Jude’s. Another son Henry followed, christened this time at St Mark’s, Easton on 5 August 1886 which suggests that they had moved from one mean dwelling to another in this poor district to the east of the City.

George the lion tamer (!) may already been absent from their lodgings in Lamb Street by the time baby Henry had the terrifying distinction of being kidnapped when just a few months old by a woman who lived in the same house. The news report in the Bristol Mercury of 1 November 1886 was succinct:

‘The woman Sarah Jane Matthews who is ‘wanted’ by the Bristol Police for stealing an infant named Henry Peters from a lodging house in St Jude’s is in custody in Malmesbury where she had been apprehended on another charge.’

The report in a Wiltshire paper was far more detailed. Sarah Jane Saunders alias Matthews had been arrested for the theft of four shawls from a Mrs Sarah Bye. Matthews, carrying ‘a mulatto child’, knocked on Mrs Bye’s door in Malmesbury late one Friday night at the end of October 1886. She asked after a man called James Ackland. Mrs Bye went with her to Ackland’s house, but he gave them short shrift, which was reported politely as ‘he was unable to take her in’. Matthews then told Mrs Bye she had walked with the baby from Cross Hands[1] where her husband had been gaoled for 3 months for abandoning her and her children. She was wet and cold and in considerable distress. Mrs Bye who felt sorry for her, offered to put her up for the night on a sofa and provided four shawls as covering in lieu of blankets. When Mrs Bye arose at 6 a.m. the next day, she found Matthews and the baby had decamped along with the shawls. By this time Sarah Jane was already knocking at another door where she told Mrs Godwin, who answered that she had been ‘walking all night carrying the baby and was trying to get to Crudwell where her father lived.’ Mrs Godwin, also took pity on her and gave her some breakfast. Sarah Jane then went to a third house, where she said she thought a ‘Mrs Matthews’ lodged. If such a person ever existed, then she had departed, but Mrs Cypher, [sic] the landlady was so moved by the woman’s pitiful state that she ‘bought a shawl, which she had no use for, and gave her a shilling for it.’ Matthews then went to the Duke of York pub and called for beer, some of which she was said to have given to the baby (an action she denied, saying she had bought milk). In the meantime Mrs Bye had gone to the police station to make a complaint with the result that Superintendent Collett tailed Matthews round Malmesbury until he arrested her at the pub. The woman and baby were taken to the station where she was charged with stealing the shawls. Further enquiries ‘by telegraph’, Bristol Mercury puffed proudly, revealed that Sarah Jane Matthews was on the wanted list for child stealing in Bristol.

The prisoner told the police she had married a Mr Matthews at Crudwell, a village four miles from Malmesbury, and was the daughter of John Saunders who lived there. The Saunders were said to be ‘hard-working folk’. The mother was sent for but denied any marriage had taken place at Crudwell, though confirmed Sarah Jane as her daughter. The family had disowned her, not having seen her for seven years until she turned up a few months before having just been released from prison.

Matthews then said she had made a mistake and had been married at All Saints, Bristol, but over the whole weekend continued to insist the baby was hers until ‘the mother’ arrived from Bristol by the midday train on Monday and identified him. It appeared Sarah Jane had asked Hannah Peters if she could mind Henry for ten minutes, but had made off with him. Henry was restored to his mother and Sarah Jane was swiftly convicted for the theft of the shawls. She was sentenced to twelve months with hard labour, with the charge of child abduction held over until the date of her release. (Devizes & Wilts Gazette page 4, Nov 4 1886) .

There was no remission of sentence or time off for good behaviour in those days so exactly a year later, Sarah Jane appeared in court in Bristol on the deferred charge of abducting the baby. Described as ‘a middle-aged woman, evidently very weak’, she had been so ill she had spent five months of the twelve in the gaol hospital. The nature of her ‘illness’ is not stated but given that nowadays convicts whose crimes involve children are often isolated because of attacks by fellow prisoners, there is no reason to think that historically it was any different.

Bristol Mercury, 10 November 1887, reported the case.

Anna [sic] Peters, the wife of George Peters, who ‘travelled with shows’, lived at 25 Lamb Street where the prisoner also had lodgings. A year before on the 17 October the baby, ‘whose name was Henry, then about three months old, was dressed in long clothes’. (Perhaps these were hand-me-downs that were far too big.) The prisoner offered to take him to her mother’s, who would ‘exchange the clothes for short ones’ and would be back in ten minutes. Hannah with three other children round her skirts, may have been glad of a few moments respite. However, when the other woman and Henry did not reappear she became alarmed and contacted the Police.

Hannah Peters declined to proceed with the charge against Sarah Jane and was lauded for her compassion under the headline

‘A Forgiving Mother’

Perhaps she was moved by the sight of the wreck of a woman in the dock. Henry, (after a fortnight’s absence!) had been returned safe and sound, and that was what Hannah most cared about. Sarah Jane was cautioned and on making a promise to do nothing like it again, left the dock a free woman. .

South Wales Echo, 10 November 1887.

The South Wales Echo, carried the most striking details:

Towards the end of the report the paper missed out the vital word ‘child’ which may account for the fact that little was made of a revelation which these days would surely cause the case to ‘go viral’. Sarah Jane Matthews was a serial child kidnapper. In 1883 and 1884 she had been charged with similar offences:

‘Sarah Jane Matthews, was sentenced at Bristol on Monday to three months hard labour for cruelly abducting a child five years old, stealing her boots, and leaving her in the bedroom of a common lodging-house where her screams attracted attention and led to her being restoref to her parents.’ (Wilts. & Glos. Standard 2 June 1883)

‘THEFT OF A CHILD. Sarah Jane Matthews, a woman approaching middle-age was charged with taking away a child aged 13 months from its parents and also sealing a sealskin hat, value 3s. 6d the property of Alice Powell. The police stated the cases against the woman were not complete and there were other charges to be preferred against her. Under the circumstanes they asked that she might be remanded and the request was granted. (Bristol Times & Mirror, 24 October 1884.)

Young Henry, pensive, wearing a rugby shirt.

The ’middle-aged’ Sarah Jane was probably in her forties when the offences took place. Her obsession with stealing babies could have meant she was trying to replace a lost child or children of her own and was past child bearing, perhaps menopausal, though undoubtedly having a child with her was a useful prop to gain sympathy – which seems to have worked. One way or another, Sarah Jane was a pathetic figure, with mental health issues. Her desperate actions provide an insight into the harsh times of lone women who sank below street level in Victorian England. After 1887 she disappears from the records, either by using a different name, or to a workhouse and imminent death.

Nothing is known of Henry until 1891 when he was with his mother Hannah and her new partner William Hart in Wales. By then his father was presumed dead, Jimmy was at the orphanage, with the whereabouts of Robert and Charlotte unknown. The family, mother, stepfather, and the three boys were reunited in Bristol by 1901.

In 1911, Henry was still single, a twenty four year plumber’s labourer, living with his mother and stepfather Bill Hart at 7 Sidney Place, Stapleton Road. By 1914 the Great War broke out. Henry served as Sapper 496420 of the 130th Field Company, Royal Engineers.

He died or was more likely killed in action on or about 10 April 1918 and is remembered on Panel 1 of the Plogsteert ‘Memorial to the Missing’, among 11,392 British and Commonwealth soldiers who fought at the Ypres

Henry in uniform: he has the haunted look of one who has witnessed horrors.

Salient and have no known graves. He is identified as ‘the son of Hannah Hart, formerly Peters, of 17 [sic] Sidney Place, Bristol.’ In her grief Hannah destroyed everything of his and never spoke of him again, which just about sums up the futility and pity of war. Hannah Hart died in Bristol aged 70 in 1929.

On the subject of 1914-18, there is a war grave at Greenbank Cemetery in the name of ‘Sapper J. Spratt, served as J. Peters, Gloucestershire Regiment, 18 May 1915.’ This was Joseph Allen Spratt, who was Robert Peters’ brother in law. No-one knows why he signed up as James Peters, though it may be guessed that he was trying to escape his past, for in 1911 he was serving ‘time’ at Portishead Nautical School for boys convicted of minor offences. Jimmy the rugby international was probably his hero. Sadly Joseph died of TB aged 19, before being posted to the front. As to the real Jimmy Peters, I wondered why he was not called up, and it occurred to me that despite being a super fit athlete he may have been considered unsuitable for military service because of the loss of his three fingers in 1910. It’s an ill wind………

Now we return to the hitherto ghostly Charlotte, not seen since she was a baby in 1881. In 1901 when the three boys had been re-united, their sister was aged 20, and also in Bristol, but had been taken in to a ‘Magdalen Home’, for girls who had ‘fallen’ or were in danger of doing so. This was a Salvation Army establishment, Grosvenor House, at 89 Ashley Road. There is no evidence that the girl had done anything untoward. I have found no records of this period in Charlotte’s life but I suspect her experience of institutional care was less positive than her brother Jimmy’s had been.

Unless people keep diaries, write letters and by some miracle these survive, it is always a mystery how one person meets another and is sufficiently impressed or desperate that they pair up and settle down together. Charlotte is next glimpsed in 1911, living at 3 Mount Street, Stourbridge, Worcestershire, with Henry Butler, an American, born in Washington DC. With them were their two daughters, Lilian May, 2 and Caroline Dorothy, two months, who were both born at Stourbridge. Henry himself filled out the census form in bold handwriting, describing, though misspelling, himself and each member of the household in turn as ‘Cullored Man’, ‘Cullored woman’, ‘Cullored child.’ [2] Henry was self-employed as a chimney sweep. You can almost hear the ‘jokes’ which he probably endured at every house by some wag who thought they were being original.

According to the census entry Charlotte and Henry had been married five years but the union seems not to have been made official until 1913 in Walsall, though the groom’s name is recorded as ‘John Butler’. [3]

Charlotte who must have had a very sad life, had at least three other children, all boys, who died in infancy. She herself died at Warrington, Cheshire in the summer of 1917 in childbirth, along with her new baby, leaving her husband and their two daughters aged nine and seven.

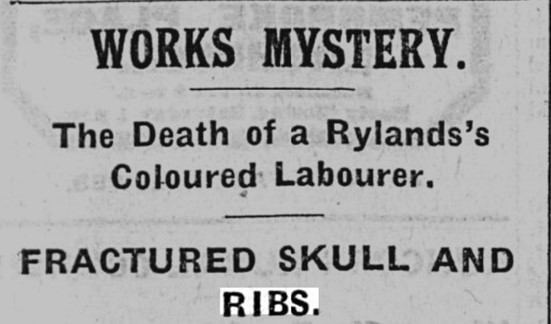

Within a few weeks of Charlotte’s death, her widower died in mysterious, even suspicious circumstances:

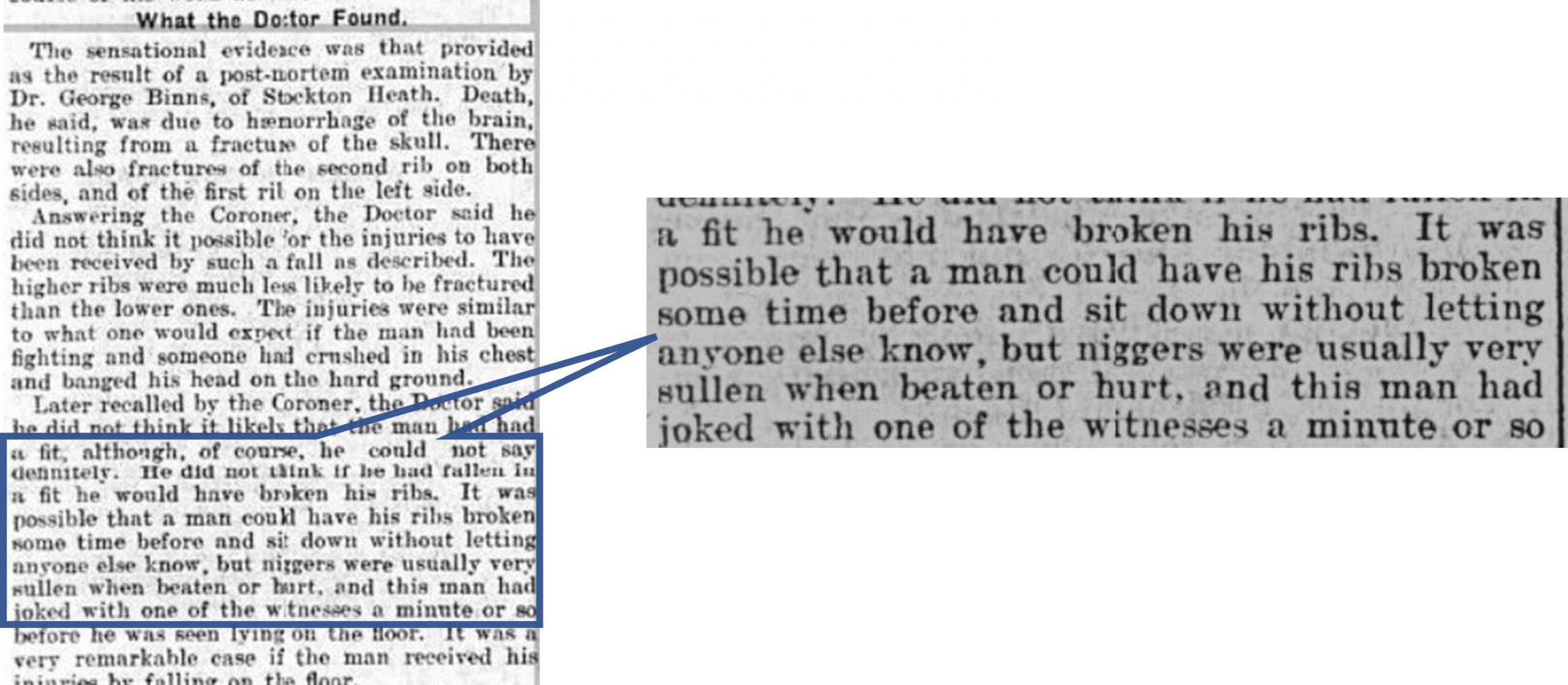

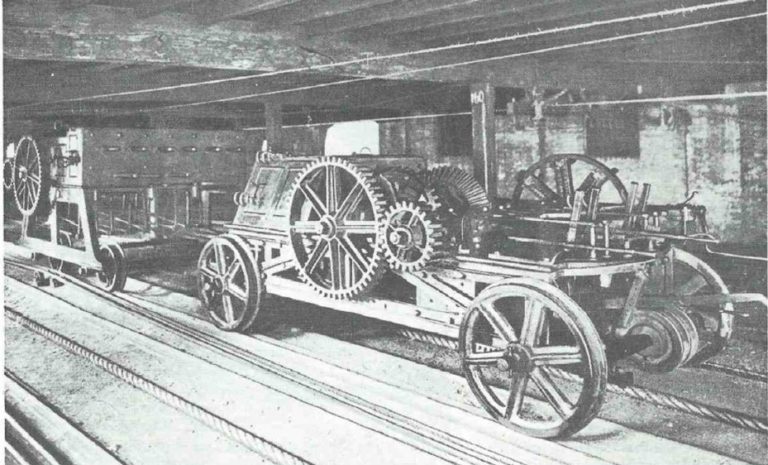

An inquest was held on Henry Butler, 45, of 15 Dolman’s Lane, Warrington. On the previous Wednesday afternoon Butler was at work at Messrs Rylands, the iron manufacturers as a general labourer. He had been in the job only three weeks. A witness, Robert Savory said he saw Butler sitting on a length of flat iron with his feet on the floor. He seemed quite well and they passed a few jocular remarks. He then went to another part of the shop and the next time he saw Butler he was unconscious, lying face down on the stone setts. Savory did not think a piece of iron could have been thrown over the rack and fallen on him. A string of other workmen gave more or less collaborative statements. Butler was taken to the Infirmary but did not regain consciousness. He died two days later.

The Runcorn Examiner 8 September 1917 has the story:

I have enlarged the statement made by Dr George Binns, supposedly an ‘educated’ man, not only for his casual use of the ‘N’ word but that he says such persons were ‘sullen when beaten or hurt’. Surely this applies to everybody?

The Coroner said it was a mystery how Butler had come by his injuries and the jury returned an open verdict. Mr Steel on behalf of the two orphans said he hoped it would not be necessary to prove legally that it was an accident to get these children provided for.

Robert Peters, a handsome lad, with a hint of mischief about him.

It seems doubtful that the children received any provision, as according to Peters family lore, the girls were placed in a local orphanage, where one of them died. The other was brought to Bristol by Robert Peters, Charlotte’s brother, but failed to settle and she returned to Warrington. For the moment this is where Charlotte’s story ends. As Kim Tozer, Robert’s granddaughter plaintively told me ‘there is no-one alive now who knows about it’.

Robert the middle of the three Peters brothers whose early childhood is said to have been spent with Jimmy ‘in the circus’ as a tumbler was married in Bristol aged twenty seven. His bride, Florence Harriet, the elder sister of Joseph Spratt who had mysteriously adopted Jimmy Peters’ name when he enlisted. Florrie, who used her middle name Harriet (as the census form of 1911 shows) was 20, the daughter of a basket maker who lived at 3 Regent Street, St Pauls. Robert, 28, was a ‘sanitary labourer’ for Bristol Corporation, a job he kept all this life, though by 1939 he was described with slightly less grandeur as a ‘Council Ashman’. This was a vital service as we all had coal fires and every galvanised iron ash-bin was full to overflowing by the time we put it outside for collection each week. The couple’s first daughter, Florence, was followed in quick succession by Irene, Ivy, Edna, Hilda, Doris and in 1925 by Leonard. There was a brief hiatus until Rita (Kim’s mother) arrived in 1930, and finally, Ivor in 1932. Robert died in 1940 aged only 54.

To end as I began with Jimmy Peters, this is possibly the last picture taken of him. The others are his son Jim, junior, born in Plymouth 1911 who I believe married Dorothy Palmer in 1938, otherwise I know nothing else about him; standing beside Jimmy is his wife Rosina Bessie, who Kim knew as ‘Aunt Cis’; the smiling lady looking through the gap is Robert’s daughter, ‘Auntie Florrie’, born in 1910, who after Robert died helped her mother look after ‘the two little ones’, one of whom was Kim’s mother.

My grateful thanks to Kim Tozer for such a fascinating assignment and for providing the photos for both articles which remain her copyright.

References

[1] Could this be Cross Hands in South Wales? Over a hundred miles.

[2] This is the only time I have seen this on a British census. Maybe someone has other examples. I wonder if the census man told Henry that this what he should write?

[3] Without seeing the marriage certificate I cannot be sure this is the right couple.

Leave a Comment