‘Peters, it may be mentioned is, as a Rugby player, English whatever his nationality proper may be.’

Western Mail, 8.9.1906.

N.B. This account contains terms that are no longer acceptable, though were in common use during the time portrayed.

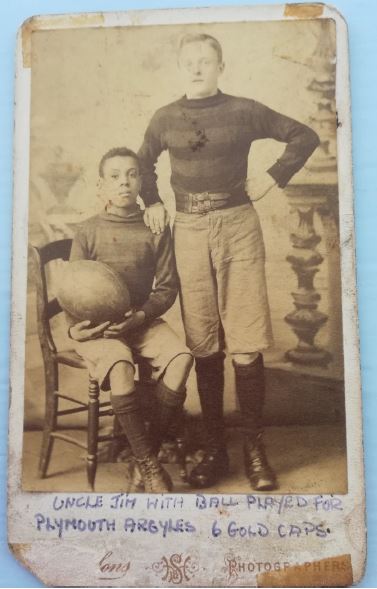

Last year, 2021, to coincide with the end of the annual ‘Six Nations’ competition, I posted a resume of the remarkable sporting life of James Peters, the first black man to play rugby for England (four times, 1906-1908), and the ONLY black player capped for England until Chris Oti in 1988, EIGHTY years later.

Kim Tozer, James Peters’ great-niece, read this short entry on my blog and I was thrilled when she contacted me: hence this expanded article, written to coincide with the 2022 ‘Six Nations’, which highlights James’ Bristol connections. To Kim and his direct descendants who are justly proud of his unique place in RU history he is loved and respected as ‘Great-Granddad’ or ‘Uncle Jimmy’.

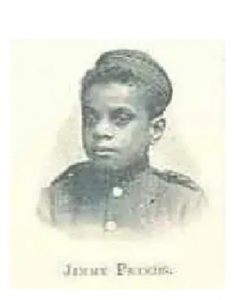

Jimmy Peters as a teenager

English Rugby is often seen as a game for ‘gentlemen’ and it is likely that the racism that Jimmy encountered from some quarters was intensified by his social class. He was both ‘different’, (the black and mixed heritage population was small)[1], and far from ‘posh’. He had led an itinerant, young life as well as living in one of the most disadvantaged districts of Bristol. He is recalled by Lesley, his great granddaughter as “a gentle-man, with ‘gentle’ being the operative word.”

Jimmy was born in Salford, Manchester on 7 August 1879. His mother, Hannah Gough, was a white woman from Wem, Shropshire, but by 1871, at the age of 13, she was living with her widowed aunt, a greengrocer in Bolton, Lancashire. George Peters, his father was born in the West Indies, though how or when he came to Britain is not known. Hannah’s suitor may have turned her head by a supposedly exciting, more glamourous alternative to life among the carrots and cabbages, for she ‘ran away to the circus’. George worked in one of the menageries, which were very popular at the time, in a most foolhardy branch of show business: he was a lion-tamer!

The young couple had an informal attitude to marriage, (no registration exists), or more likely encountered disapproval from family and friends, so bravely ‘jumped over the broom’. At the census of 1881 they were a family of four living in a shared house, (two families, eleven people) in the working class district of Scotland, Liverpool, (famous as the birthplace of Cilla Black!) Jimmy was a toddler, nearly two, his baby sister Charlotte, born in January that year was a few months old. On her birth certificate George is described as a travelling showman.

By 1883 for some reason the Peters family had arrived in Bristol where their third child, Robert (Kim’s grandfather) was born on the 10th January ‘outside the gate’ in the poor parish of St Philip and St Jacob, east of the City. George found a more mundane line of work: he was described as ‘a day-labourer in a brickyard’. Robert was baptised at St Jude’s on the 2nd February. Coincidentally, on this same date, a famous menagerie, Wombwell’s, was drawing crowds at the Horsefair in the City centre. It may be that George was lured into looking for a job working with the lions there – but if he was successful he was not the main man. The Wombwell’s lion-tamer, interviewed by the Bristol Magpie in January 1883 was ‘the famous Ledger Delmonico’.[2] A third son, Henry, was born and baptised at St Mark’s, Easton, on 5 August 1886. No father is named on his birth certificate. It could be that George was away travelling or perhaps there are other implications. In any case George disappears from the story between the time of Henry’s birth and 1889 when Jimmy was about nine or ten. George is said to have met with an accident, and was ‘killed – by a lion!’

Jimmy and his younger brother Robert spent their early years travelling around with the circus as clowns, tumblers, even trick acting on horses. Then Jimmy, by himself, though still under ten years old, was placed by his mother in a troupe in the South of England, possibly at Blandford, Dorset where he performed as a bare-backed rider. When executing one of his perilous manoeuvres, balancing on the back of the moving horse he was thrown and broke his arm. Having become a liability and of no further use to the travellers, they moved on, abandoning the little boy. Destitute and perhaps begging in order to stay alive, his plight touched the heart of a Miss Daniel, the daughter of the doctor/surgeon to Lord and Lady Portman who brought Jimmy to their attention. Whatever the circumstances it appears that the Portmans concerned themselves with the child’s welfare and the result was his admittance to Fegan’s Orphanage for boys in Southwark, and later, The Little Wanderers in Greenwich. He arrived ‘without papers’ in November 1890 and checked in at four foot six and a quarter inches tall, weighing 5 stone 6lbs. In 1891 Jimmy is recorded among the inmates of Mr Fegan’s Home, aged ten, his birthplace shown incorrectly as Bristol.

Meanwhile, Hannah Peters, his mother, had found a new partner, William Hart, and in 1891, with Hannah’s son Henry, (named as Henry Hart) they were at Presteigne in Wales. William was a ‘hawker’, a precarious occupation from which we may deduce that theirs was a bleak existence not far from the breadline, knocking at generally unwelcoming doors, and always on the move. The trio are the only members of the family recorded by that census. Where were Charlotte and Robert?

Meanwhile, Hannah Peters, his mother, had found a new partner, William Hart, and in 1891, with Hannah’s son Henry, (named as Henry Hart) they were at Presteigne in Wales. William was a ‘hawker’, a precarious occupation from which we may deduce that theirs was a bleak existence not far from the breadline, knocking at generally unwelcoming doors, and always on the move. The trio are the only members of the family recorded by that census. Where were Charlotte and Robert?

Being in an orphanage is not usually considered lucky but it was the making of young Jimmy. At Fegan’s with its rigorous Christian regime, compulsory prayers and Bible classes, (he could quote the Bible verbatim and was a life-long teetotaller), he learned to read and write and was also taught skills, carpentry and possibly printing. Moreover his athletic prowess was noticed and encouraged. Fegan’s magazine, ‘The Rescue’ includes a few pen-portraits of the young sportsman. Clearly, his arm injury had healed, and he was

‘….all joints and springs inside, resilient as India rubber, in some parts hard as ebony and nearly as black in others……’

At one sports day he won every event, the 100 yards, high jump, long jump, the mile, the walking race, kicking the football and throwing the cricket ball:

‘….but we all felt his best performance that day was when he gave up one of his prizes to another fellow who had been his close rival……..’

‘Jimmy was raised in the circus and as a bare-backed rider met with an accident. He was deserted by the troupe to which his mother had sent him. Providence brought him to us, where he has been cared for ever since. His father met with a horrifying death in a lion’s cage….’ [3]

This phrase about George’s sad end continues to be parroted in every later report when Jimmy’s origins are mentioned. It appears to be the first contemporary documentary source to prove that it happened at all and even then it is hearsay. There is no death certificate for George to fit the known trail of dates.

Certainly there was a vogue for black lion-tamers, as many advertisements in the theatrical paper The Era testify, often with ‘Coloured’ or ‘Black Man preferred’ appended. One imagines the chosen applicant would be presented in an ‘authentic’ jungle tableau, kitted out in a grass skirt, beads and exotic plumage, even required to bellow in an ‘unknown’ language. Accidents were regularly recorded as ‘exciting scenes’ suggestive of cheap thrills:

‘.…blood poured from the wounds and the crowded audience rushed out of the menagerie causing panic in the busy fairground…’

or

‘a coloured lion-tamer named Beaumont was bitten by a lioness at Bolton. His hand was severely lacerated. The spectators ran from the scene in great fright….’ [4] Beaumont was killed by a lion a few years later.

George Peters does not feature in any such reports; he may have used an alias, and is hiding under his assumed name, or, so much for the glamour, was of such a lowly a variety of lion-tamer, a cleaner-out of cages that he was of little account. Or he may simply have vanished off the face of the earth with a suitable tale concocted to account for his absence.

At the Home, Jimmy was a star. He became Captain of Games and Mr Fegan’s ‘Door Boy’, a favoured position. The Portmans continued to be pleased by his progress and sent him parcels of ’tuck’ and pocket money. He played rugby for the nearby Blackheath Club; (its present day successor, Greenwich Admirals, a Rugby League side, even now celebrate him with an annual challenge match.) In 1898 as soon as he was 18 Jimmy was obliged to leave the Home. He came back to Bristol where his mother and stepfather had settled in The Dings, a notorious slum district of St Philips & Barton Hill, known for poverty and degradation. A Mission, the Shaftesbury Crusade, had been set up there to improve the lot of the poor which encouraged sporting activity as a way of keeping the men out of the pubs. In 1897 Herbert William Rudge, the young son of a Clifton surgeon, founded a rugby team, the Dings Crusaders, as part of the Dings Boys Club. It was almost tailor-made for Jimmy, his second big stroke of luck. Playing for the Crusaders he was spotted by other local teams, significantly the Bristol side itself, though his inclusion was not without controversy. A board member is said to have resigned in protest, and other vile interventions are recorded in letters in the press, ‘a pallid blackamoor…….doing a white man out of a place in the side’.[5]

Sydney Alley, ca 1900 by Samuel Loxton, (by kind permission Bristol Ref Library)

Nevertheless, throughout 1900 Peters was regularly playing at half-back for the Bristol Second XV: ‘Peters snapped up the ball and dropped one over the line’.[6]

In 1901 Jimmy, then 20, lived with his family (minus Charlotte) at 10 Sydney Place, Stapleton Road. William Hart was 49, born in Manchester, Hannah, his wife, 41, with Jimmy’s brothers Robert, 18, and Henry, 14, an errand boy. Jimmy, like his stepfather and brother was a ‘general labourer’. This may indicate that he had difficulty in following the trade for which he had been trained, but also highlights the amount of dedication required, that after a week of hard manual work, he turned out on the rugby field.

In 1901-2 Jimmy played for the Bristol First XV. Match reports show that he often distinguished himself:

‘A fine kick by Baker and follow up by Peters increased the advantage’.

‘Peters had the honour of scoring and got to be quite a favourite before the match ended. He beat Frear – an Irish international – very cleverly when he scored and apart from that made half a dozen beautiful runs.’

The reports did not mince words when he had a poor match, especially when it happened more than once ‘Peters missed another pass’ and on one occasion his ‘lack of speed’ (!) meant the loss of a try. No reference was made to the colour of his skin, though reminiscences of a former Bristol teammate, R.L.A. (Bob) Bryan, printed years later in 1934, shows that he was known as ‘Darkie’ Peters, though it has to be said many other players mentioned in the piece also have nick-names. The article compares the contrasting personalities of two former players:

‘Don Alcazar comes to mind, a very dark chap with the typical Spanish Aspect, mentioned to show the cosmopolitan side of Bristol some forty years ago (sic). He played with Darkie Peters, but what a difference in the two temperaments. The Don was the cheeriest of souls, full of fun and frolics and the liveliest of a lively crowd after the match. Darkie Peters was a rather morose chap, and not a bit like the general run of folk to whom the term ‘Darkie’ is usually applied.’ [7]

Leaving aside the ‘Amos ‘n Andy’ stereotypes popular at that time, consider the outsider, (even if without malice) referenced by race, the religiously inclined total abstainer, rendered uncomfortable by the after match ‘fun’ perhaps fuelled by alcohol. Azeem Rafiq in the present day, Jimmy, 1902?

During his time in Bristol Jimmy also played for Knowle. ‘Peters scored for Knowle against Bath with a fine kick’ and for the same club against Frome ‘with a pretty try’.[8]

In my previous post, I maligned the Knowle Club by suggesting that some members had resigned when Jimmy was included in the side. I made a mistake by careless reading as it seems that the resignations were at the larger Bristol club.[9] I apologise for this slur against Knowle. A report from the Club’s AGM in June 1902 has a more positive slant. Jimmy had been honoured by selection for his county, Somerset, but there had been a hitch.

‘Last year, J. Peters who played half for Knowle gained his Somerset County Cap but owing to want of funds the county authorities were unable to supply him with one.’

The President of the Knowle Club, Mr Stroud, stepped in and generously offered to supply the Cap himself if the County agreed.

‘Permission was granted and at the meeting the presentation was made to J. Peters by Mr Stroud who wished him every success in his future career.’[10]

At this time Jimmy was preparing to leave Bristol, both Club and City. Quite often good players were enticed by clubs with offers of employment. Whether this happened in Peters’ case is not known but by September he had a job in Plymouth Dockyard as a carpenter, and a place in the local Rugby Club side. He spent the rest of his RU career 1902-1909 at Plymouth and in 1907 married a local girl, Rosina Bessie Finch. He added several Devon County Caps to his honours, though hopefully was able to afford his own Cap if his new county, like his old, was similarly strapped for cash.

Back in Bristol, in late summer 1902, some ‘pessimists’ were concerned for the coming season. Several prominent players ‘whose loss to the Club would be felt’ had left, among them ‘J. Peters who was full of promise, one of the best halves the Club has known. [11]

Success with Plymouth and Devon led to a clamour for Jimmy’s selection for the national team. He and R. A. Jago of Devonport Albion made a formidable duo:

‘Without criticising individuals in a great game one can hardly refrain from referring to the great form displayed by Jago and Peters. They stood out in strong contrast to the other pair of halves and the opinion all round was that they should play for England next Saturday. The Powers that be have decided otherwise. Peters is sacrificed. Colour is the difficulty. Peters is sacrificed, pity for the chance of English success. But those who sit in judgment seem to think that in an international match the bar to Peters is insuperable. Are they right?’ [12]

After the County final, between Durham and Devon, in which Jimmy ‘was superb, continually setting his threequarters in motion’,[13] he could be ignored no longer. On the 17th March 1906 he was t last picked to play for England, though opinion was divided: the Yorkshire Post stated ‘his inclusion was by no means popular on racial grounds’. He played for England against Scotland in Edinburgh: England won 9-3. Five days later, the 22nd March, he scored a try in his second international, against France in Paris: England won 35-8. The Sportsman newspaper commented ‘the dusky Plymouth man did good things, especially in passing’. For England, wins in the last two matches of the season, those in which Peters participated, were welcome, but Les Bleus were not at this time part of the Championship so the result did not count. England finished at the bottom of the ‘Four Nations’ table having lost to Wales and Ireland.

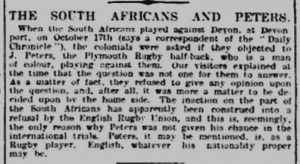

Between October and December 1906 Jimmy became embroiled in a political inferno. He was expected to play for Devon against the touring Springboks side. The visitors were asked whether they objected to playing if a ‘coloured’ player was included in the county side. The South Africans declined to comment. The Devon selectors took this as a negative reply and cravenly capitulated.

Western Mail, 8.9.1906.

The final line is curious.

It may be that with the Boer War only four years in the past it was felt necessary to omit Peters for ‘the good of the Empire’. Whatever the reason Peters was duly dropped from the County side and in the subsequent international match he was once more ‘sacrificed’. Jago, back in the team after absence due to work, played with another partner. Against a ‘weakened’ Springboks side, on 8th December at Crystal Palace England could only manage a 3-3 draw.

Peters played twice more for England in 1907 and 1908, both times against UK sides.

In February 1910 he met with a horrendous accident which was reported with deference – note the ‘Mr’ – and even pride:

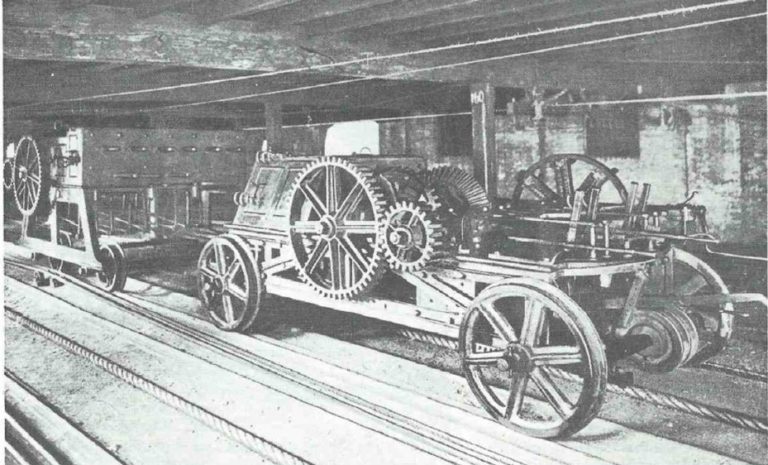

‘Mr James Peters, the Devon County and former International Rugby half back was at work at Plymouth on Tuesday when three fingers of his left hand were severed by a steam planing machine.’ [14]

It was surely feared he would never play Rugby again and the disaster could account for the census entry of 1911 when he was ‘a publican’, probably one of very few teetotallers in the hospitality trade! He gave his age as – ‘30’ – and stated incorrectly that he was born in Bristol. By then Jimmy and Rosina had a three year old daughter, Rosina Florence. Also living with them at 14 Buckwell Road were his parents in law, George, a wagoner, and Bessie Finch, with their four children aged between 22 and eight years old.

Apart from the County games, in Rugby football although individual matches were fiercely competitive, they were all ‘friendlies’ with no knock-outs or other competitions to show superiority of one club over the rest. The Rugby Football Union was adamantly against a League which smacked of the dreaded ‘professionalism’. The accident had finished Jimmy’s international career but against the odds he made a comeback to rugby. He played in the County side for which he received a small fee and was banned from Rugby Union. There was furore when the clubs in the South West of England attempted to form a League, an illegal action according to RFU codes. With Peters exiled and many other players suspended, the Plymouth club folded.

Disillusioned, Jimmy went North and signed for Barrow in the Rugby League. In sports columns he had so far been reported as ‘J. Peters’ or simply ‘Peters’, but now they called him by name. ‘The correspondent of the Barrow Herald, who wrote as ‘Referee’, on 15 November 1913 was highly impressed:

‘After Barrow had missed two tries, Keighley were penalised. It was not an easy position and I had my doubts when James Peters was called up to have a kick at goal. They tell me he has kicked some wonderful goals in ‘A’ Team matches and on this occasion he sent the ball truly between the posts. A great goal. Then Joe Doyle, George Dobson and James Peters put the hat on Keighley; Dobson put the ball between the posts and Peters kicked the goal..………. James Peters was the favourite of the crowd and deserved their favouritism. Everything he does is with cleanness and nippiness that points to class play. His side-step is bewildering and his passes so swift that at times they are not taken. His place kicking is phenomenal.’

But the euphoria was not shared by all. The beast raised is ugly head again. The Committee was accused of ‘ignoring the claims of Peters to be picked for the senior team’, with the excuse that Percy Thomas, the other half back did not play well with him. However, the Lancashire Post demanded ‘a better explanation……’ Thomas had been consulted and stated ‘unofficially’ that he would not play in the team unless Peters was removed. Peters was not included.

The reporter reiterated: ‘the present silence is not to the liking of the supporters and some players. If the Committee is showing a special favour to one player over another by heeding his wishes there is need of an explanation.’ [15]

Jimmy Peters in 1951

This new controversy no doubt left a sour taste and the next few months could not have been happy for Jimmy. By November he was on the move again:

‘St Helen’s Rugby have made one of their best captures having come to an understanding with Barrow for the transfer of James Peters, ex English international half-back. Peters is now employed in the St Helen’s area and will turn out against Dewsbury.’[16]

Jimmy’s new start was overtaken by events on the World stage. Since August the country had been at war, which was not ‘over by Christmas’ as initial enthusiasm had predicted. The Government discouraged all professional sport for the duration. Competitions were suspended. St Helen’s struggled on though found it difficult to find sufficient players to form a team. Jimmy played only twice for his new Club.

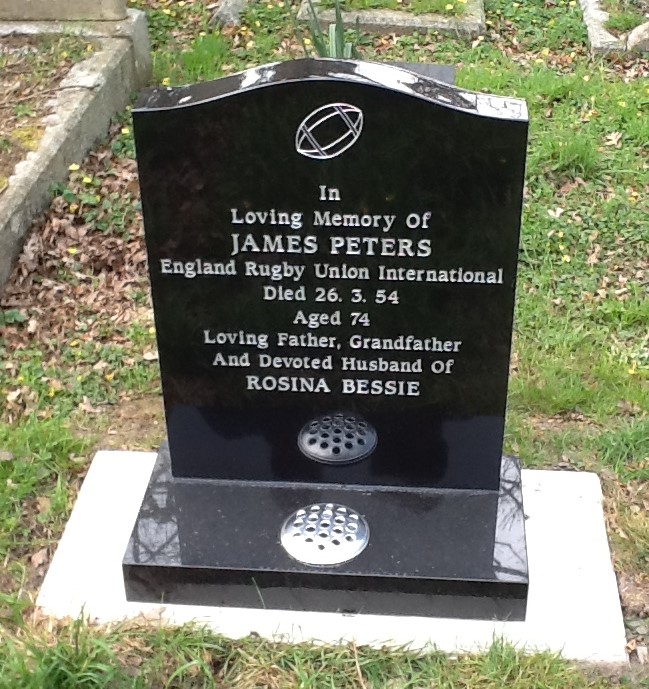

With his sporting career at an end, he returned to live in Plymouth. In 1939 when registered at the start of the Second World War, he and Rosina were living at 36 Cobourg Street. James Peters was working as a carpenter at the shipyard, and still unsure of his age, recorded his birthdate as 7 August 1880. He died on 26 March 1954:

Jimmy Peters headstone

Thanks to Debra Jenkins and ‘Lesley’, his great granddaughters and Janette Ward, his great niece, whose comments are online and especially to Kim Tozer, another great niece. I am grateful to Kim for drawing my attention to the splendid Radio Bristol programme about Jimmy now on BBC radio iPlayer at https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p07nksh2

My attempt at telling Jimmy’s story pales by comparison with Thomas Weir’s fine academic dissertation ‘James Peters: The man they wouldnt play’ (De Montford University, 2015). Aside from the scholarship, it is also ‘a very good read’.

The family members Jimmy left behind in Bristol have their own interesting story which will be told in Part 2.

——————————————————————————–

[1] Weir, Thomas, ‘The Man They Wouldn’t Play’. In JP’s time estimated at less than 50,000 and centred around large ports like Bristol.

[2] 4.1. & 1.2.1883

[3] https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p07nksh2

[4] The Era 7.1.,22.4, 22.7, 28.10. 1893, et al.

[5] BBC, ibid

[6] BTM 10.12.1900, WDP 14.9, 28.9, 5.10.1900, et al

[7] WDP 20.4. 1901, 2 April 1902, 21 April 1902, 23.2.1934 et al

[8] Clifton Society 13.3.1902, WDP 17.3.1902)

[9] See BBC, above, though the reference to the resignation in non-specific.

[10] BTM 12.6.1902.

[11] WDP 21.9.1902

[12] Western Times, 5.2.1906. Half-backs are more usually known these days as ‘scrum half’ & ‘fly half’.

[13] The Sportsman, 11.3.1906

[14] Exmouth Journal, 12.2.1910. Note the deference.

[15] Lancs Daily Post 17.12.1913

[16] Liverpool Echo, 19.11.1914

Blog Comments

Kim

27th March 2022 at 7:41 pm

Thank you.

Thank you for getting Jimmy and his story out there.

Phil Baker

26th February 2023 at 11:58 am

I just wanted to say a big thank you for your piece written back in February about James Peters.

I am volunteering to do some work for Plymouth Albion Rugby Club and we are looking to erect a statue of Peters at our home ground of Brickfields in 2026 (the club’s 150th anniversary – http://www.plymouthalbion.com/project-150/). I am helping out by doing some work around their website to help promote the fundraising efforts a little more to reach our target. Having spent the past day or so looking into the life of Peters and his family history, to give a little more context to his life, I found your website and piece, which has offered such a great insight into his life. Funnily enough I am now based in Bristol so have enjoyed exploring a few topics a bit further, but the piece of Peters is excellent and I have learnt so much more than i previously knew about the man.

I’m sure you will agree that the Peters story is not known widely enough and an aim of mine is to make sure his story is shared further afield, but without your piece i wouldn’t have known half the story myself, so many thanks for your hard work on it.

With your permission, would it be okay to reference your piece on our website and as a useful place for people to find out more information about James Peters?

Many thanks,

Phil Baker