We had it pretty sticky for a few days – our casualties up to Wednesday were approximately a thousand, The Gloucesters were over 600 and the other two battalions about 150 each.”

L/Cpl Arthur Stone to his parents, 29 April 1951.

I’m always looking out for people whose lives took an unexpected turn. At a recent meeting at Knowle & Totterdown History Society, I gave a talk about Perrett Park and its founder, C.R. Perrett. (see a previous blog). Many members played in the Park in their young days but Russell Evans’ memories were specific. His ‘Uncle Norman’, otherwise Norman J. Mounter, was a keeper at Perrett Park. (Remember when there were such people?)

“Air raid shelters were still in the Park when we used to visit him with Mum,” Russ told me. “Us kids would want to play in them, but they tried to put us off with a gruesome tale. Once upon a time a bloody bundle of rags had been found there – and inside was a lump of flesh…..the shape and size of a baby! They never found who’d done it. For all we knew, the monster might still be at large, lurking in the dark, ready to jump out on us.”

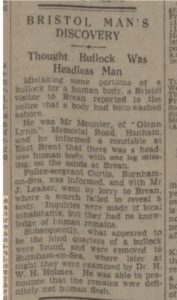

You can imagine the children, rapt gob stopper eyes, and their squeals of delicious spine-tingling terror………! Over time, like many such stories, it had been bent slightly to fit the current circumstances. The grisly parcel – surely this was not different one? – was not found in ‘Perrett’s’ but at the seaside at Brean as reported on 13 August 1947 by the Western Daily Press.

You can imagine the children, rapt gob stopper eyes, and their squeals of delicious spine-tingling terror………! Over time, like many such stories, it had been bent slightly to fit the current circumstances. The grisly parcel – surely this was not different one? – was not found in ‘Perrett’s’ but at the seaside at Brean as reported on 13 August 1947 by the Western Daily Press.

A visitor to the resort, a ‘Mr Mounter of Memorial Road, Hanham’ was said to have found a headless human body with one leg missing washed up on the sands. He alerted the Police. There was a flurry of excitement and soon PS Curtis, the local bobby and a Mr J. Leaker were on their way from Burnham by lorry to investigate. At first their labours were in vain, but later ‘the hind quarters of a bullock were found and removed’. The remains were examined by a doctor who said they were ‘definitely not human flesh.’

An anti-climax certainly, but a cover-up? Mr Mounter may have tapped his nose and said “I know what I know…” Make up your own mind, but the consensus was that ‘the body’ was a joint of rotten meat dumped there by a thief who had lost his nerve.

This ‘Mr Mounter’, was not ‘Uncle Norman’ himself but may have been his father Jim, who in 1939 was living with his wife Elizabeth and the first six of their large family at 4 Hanham Mills Cottages, Kingwood.

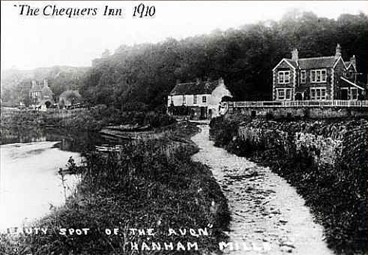

The Chequers and cottages at Hanham Weir in 1910

The cottage still exists, just down from the Chequers pub, though “It’s a lot posher nowadays,” Russ says. “It had no electric, no running water, apart from condensation on the walls, an outside loo, or bucket and chuck it, Mum said, I can’t remember which.” (Mum was June, Norman’s sister, two years his junior.)

Elizabeth, Norman and June’s mother, had her own noteworthy, though sad, history. She never met her father, or knew who he was; she was one of the last babies born in the old Fishponds Workhouse. When her mother Amy married her stepfather would not allow her to take his name so Knapp she remained though her brothers had a different surname. (Something else in common with Mr Perrett.)

James Eric Mounter and Elizabeth Knapp were married in 1928. Jim Mounter was employed by the Port of Bristol Authority and worked on the tugs at Avonmouth and Bristol docks. Their nine children born over the next twenty years included twin girls in 1936. By 1939, Jim was a railway labourer. But this story is supposed to be about Norman, their second child, who was born on 5 January 1932.

In January 1949 the Government gave Norman an unwelcome 17th birthday present. This was exactly the date the National Service Act came into force. From 1945 onwards most of the men who had fought for the six years of the war had been demobbed leaving the armed forces seriously under strength, but Britain still had commitments in various parts of the World and ‘The Act’ was considered the only way to make up the deficit. All physically fit males between the ages of 17 and 21 were required to serve in the army, navy or air force for an 18 month period, plus four years in reserve. Norman became ‘Number 22378777, Private Mounter, N.J.’ of the Gloucestershire Regiment.

On 25 June 1950 North Korea, supported by the Chinese and Soviet Russia, invaded South Korea. Eighteen year old Norman was deployed along with the UN Force to repel the invasion. Possibly the farthest the young man had previously travelled was that family trip to Brean. Perhaps by this time, he looked upon his mobilisation as an adventure, a free cruise, and a chance to savour other faraway delights. This was what David Green, a Gloster, of about Norman’s age, thought.[1]

All that Norman told Russ’s Dad of what happened next were the ‘bare bones’, that he “was captured by the Chinese at the Imjin River, marched off to the POW camp and like many others, was tortured.” With only this fragment to go on, this tale relies on the voices of others, particularly Green and Tom Clough, a young Gunner of 170 Mortar Battery which fought beside the Glosters.

On 1 October 1950, 890 officers and men of the Glosters (regulars, reservists and national servicemen) commanded by Lieut-Col J.W. ‘Fred’ Carne, left Southampton for Korea, as part of the 29th Independent Brigade. So much for ‘the cruise’, the voyage aboard a crammed troop ship was not much fun and took up to six weeks. On 3rd November they docked in Pusan (now Busan) and were grandly piped ashore by an African-American military band. ‘In typical fashion our trucks were on the wrong ship so we travelled north by train.’ [2] They had advanced 50 miles north of Pyongyang in North Korea, when the Chinese took a firmer hand. They crossed the Yalu River with armies totalling over 300,000 men.

It has been said that ‘the British Army never retreats but makes a tactical withdrawal’. The 29th Brigade pulled back several hundred miles, south of the 38th Parallel where they dug in for the bitterly cold winter 1950/51. In February 1951, the Glosters took Hill 327, creating a buffer zone north of Seoul. For the first time Tom Clough saw men blown up, a horror he still recalled years later ‘as if in slow motion’. Seoul which had changed hands four times was in ruins.

‘……..abandoned Seoul, its once majestic buildings battered into mere shells, a grim witness to the passage of defeated armies…….the refugees were on the move once more throwing dead and new born babies into the river as they left.’[3]

‘After that we went to the Imjin, south of the river. The weather was like an English spring. The enemy was nowhere in sight.’ [4]

The British were strung out along hilltops with the Belgian Battalion to the north. Their Spring Offensive underway, the Chinese advanced, and struck on the 22 April 1951. Their infantry waded across the Imjin.

‘….like migrating wildebeest……. no matter how many fell and floated down the river there were others to replace them, herded by the officers waving pistols, said to be shooting any who tried to turn back.’ [5]

Bloody fighting ensued involving tanks and aircraft and at last, under enormous pressure, the main groups were evacuated until only the Glosters remained, pushed back on to Hill 235.

‘I have no idea how we managed to get up there with all our equipment – fear probably! I realised then that we were in trouble…..yet strange as it sounds, once we were up the hill I didn’t feel scared, but of course there were moments of terror. As to the Chinese, they were either very brave or else very frightened, forced to attack by people behind them. I still felt hopeful as we had a bit of ammunition……” [6]

After three days of intense fighting things were ‘pretty desperate’ but they fought on, with little ammunition. Still the Chinese kept coming. ‘We resorted to throwing stones at the enemy. It was all we had left. It was the bloodiest battle fought by the British army since the end of World War 2.’[7]

They now had very little water and food left and they also had many wounded. At last in danger of becoming completely overwhelmed they were ordered to attempt a break out, get off the hill and down into a valley. It was now every man for himself. The dead were left behind, but the Padre, the Medical Officer and others stayed behind with the wounded in a selfless act of courage. The exhausted men staggered down the hill.

Clough naively thought they would be able to fight their way out. With only two or three bullets left he shot a Chinese soldier ‘to prevent him shooting me’ He was with a small band, ‘bloodied and bedraggled from three days of battle’ in a muddy farmyard when Chinese troops came on them from all sides. One of their officers marched up and said

‘For you, the war is over’.

They had heard this line so often in war films that they all doubled up laughing. The bewildered official, who obviously had been pleased with mastering such a grand English phrase, departed, shaking his head…. Who were these idiots? ‘but we were all taken prisoner anyway.’ [8]

Green scrambled down the hillside alone, desperate for water. He had not had a drink for three days and blissfully slaked his thirst in a clear shallow stream, lying face down and debating whether to play dead. He abandoned the plan by imagining a bayonet in his back. Suddenly he looked up, ‘amazed to see a horde of armed but lightly clad Chinese, all smiles and handshakes, surrounding our blokes’.

Instead of the layers of British Army issue clothing he was wearing against the harsh Korean winter, Green saw that the Chinese were already in light summer garb, and on their feet in place of boots wore tattered ‘daps’.[9] ‘An officer told us we were safe now, in the hands of the People’s Republic. No longer cannon fodder for the warmongering Americans.’

(Six hundred and fifty Glosters held off 10,000 Chinese for three days in their epic stand. Fifty nine Glosters were killed with 522 taken prisoner. A hundred and eighty of these were wounded, and thirty four more died in captivity. Hill 235 was renamed Gloster Hill. The 1st Battalion of the Gloucester Regiment and Troop C of the 170th Mortar Battery were awarded the United States Presidential Unit Citation, the highest American award for heroism and collective gallantry.

As a whole, the 29th Brigade’s courageous stand provided the UN forces with the chance to re-group and block the Chinese advance on Seoul. The Imjin fighting marked the end of the mobile phase of the war and stalemate ensued.)

One of Glosters called out ‘how about some chop, chop then, Mush?’ They had eaten very little for the last three days but the handing out of food proved an alien concept. The Chinese soldier in the field carried his own rations, dry goods, cooked, powdered soya beans and peanuts, easily mixed with water to form a mash. The prisoners were kept alive with boiled water, but it was eight days before they were fortified for the ordeal ahead and served with their first meal, a watery soup of gritty grains. Their stomachs had shrunk so much the meagre fare satisfied them but for some, dysentery followed.

With the most seriously wounded left at a ‘halfway house’ they crossed to ‘the wrong side of the Imjin’. Green established a rapport with the guard who marched beside him, a cheerful, portly soul who was fascinated by the clink of Green’s army boots and liked to examine their metal hobnails and toecaps. Green sorely missed his ‘fat friend’ when after a hundred odd miles the shift changed over and his companion was replaced by a less amiable guard. He was grateful though for Chinese discipline when the column encountered trigger-happy North Korean stragglers who demanded the Chinese shoot the prisoners. The Chinese pulled rank, the Koreans were sent packing and the march proceeded. The prisoners were now being fed, coarse rice and millet, but on this diet Green kept surprisingly healthy, except for being seriously troubled by blisters and the lack of tobacco.

After tramping for six weeks over 600 miles, Norman Mounter and the others arrived at the prison camp at Chong Song. It consisted of a series of round barracks, (Norman was housed in 29B), in the middle of a village occupied by the Chinese forces. Rather than barbed wire it was ringed by heavily armed manpower. The British officers and senior NCOs were removed very soon after their arrival.

The inevitable dysentery, jaundice, cholera and yellow fever took its toll. The first of the British group to die was ‘Taffy’ Moseley, their cook. Many of the POWs died. The Americans, who were kept in a separate compound, were treated much worse than the British who were shocked by the low morale, physical appearance and mental suffering of their allies.[10] Green describes their sick laid out by the roadside by day and at night dragged inside by their compatriots. Americans carrying shovels, going up to ‘Boot Hill’, the burial ground, became a familiar sight, a dismal procession which Clough once saw enacted 15 times in one day.

The British, classed as ‘dupes of the American warmongers’ aroused in their captors a possibility for re-education. Subjected to long periods of indoctrination, they were kept sitting upright on the ground for hours. Green hoarded a few odd pieces of wood and knocked them together to form a rough stool which slightly alleviated his discomfort. He whiled away the hours of the harangue by lusting after the female monitor (he named her Myrtle, but did not approve of her boyish haircut) who was assigned to report his progress. He liked to think his feelings were reciprocated.

‘Smokes’ continued to be a difficulty. When someone managed to barter something for a bit of tobacco they derived great pleasure rolling cigarettes from the propaganda newspapers which were freely available. Matches were another problem. Green who had done a bit of ‘time’ in civvy street, knew the trick of cutting a match into four, but these matches were made of wax.

They were now regularly fed, maize, with even a few greens on occasion; then they were introduced to sorghum, a pink coloured grain more usually fed to cattle in the west but a main staple in many parts of the world. The taste had to be acquired and many POWs could not stomach it.[11]

On a glorious occasion a wild hog was run over and found in the street by one of the instructors. The beast was laid out on a trestle table by the Chinese cooks who cut into the skin of all four trotters and inserted steel rods into the incisions. Two fore legs and one hind leg were then bound up and one of the cooks with powerful lungs blew into the fourth leg. When the pig had swelled up like a balloon (amid much cheering) they tied down the last leg and turned him over, four legs up to the sky, and suspended him over a barrel of boiling water. He was then deftly scraped until every last hair was off, making him ready for the pot. ‘The poor pig would never know the adrenaline he aroused …manna from Heaven’.[12] The meat was shared among 150 men in Green’s section all given two small pieces of pork the size of Oxo cubes, a delicious pot of stock, and rice, a special treat in itself.

They were all alive with lice and spent a good hour each day delousing. There was great relief when ‘Lofty’ Simms somehow got hold of a pair of hair clippers and gave everyone a haircut.

‘Mohicans before they were fashionable, and tonsures like monks, or all shaved off.’ [13]

The useful Lofty accomplished the shaves with a razor fashioned from a six inch nail.

As far as possible they kept fit with physical exercise. Occasionally even some of the emaciated Americans separated by the road managed to join in. In the finest POW tradition, the British put on variety shows, held ballroom dancing classes, and even took imaginary dogs for walks round the perimeter. But the best were the songs. Prisoners, guards and even Korean peasants all enjoyed these evenings. The Koreans would line up along the footpath between the British and American compounds when, in good voice loud enough for all to hear, Archie Coram would strike up ‘The Blackbird’ with one minor alteration, in the broad ‘Glaaaster’ vernacular:

Where be that blackbird to?

I know where ee be

Ee be up that paddy field

An’ I be aader ee.Ee sees I an’ I see ee

We both see one an t’other

With a whopping gurt stick

I’ll knock ee down

Blackbird……. I’ll ‘ave ee!

The jolly mood could change in a wink, with rifles pointed in anger should there be any mention of Chairman Mao.

These events attempted to keep negativity at bay. The POWs’ lives were suspended as each day succeeded each dreary day. They heard no outside news, had no idea when (if) they would ever be released. The King, George VI, died suddenly and the new Queen ascended without their knowledge. They were not allowed to send letters home, only cards stating they were being well treated. Tom Clough spent his 21st birthday in the camp.

There was an ‘escape committee’ and both Clough and Green were among those who tried to get away. Both were caught. Clough, hands behind his back, in handcuffs which cut into his wrists, was held in a small privy, in darkness apart from a tiny beam of light from a crack in the door. Like Robert the Bruce, his only company was a spider which he watched for many hours as she spun her web and patiently awaited her prey. He was dragged out in the middle of the nights for repeated interrogations, brainwashed, threatened with deportation to Manchuria, which terrified him. He gave out fictitious names, cowboys, Tom Mix and John Wayne. Then real names, first ‘progressives’, prisoners who had shown sympathy to the Communist cause, who he hoped would not be treated too harshly. When they could get no more out of him, he was put in a barn, known as the Kennel Club, inside a small cage where he could only just sit up. He was eventually sentenced to six weeks hard labour in a lumber camp; a big improvement, as he got to eat the same food as the guards. On release he was mistakenly led through the American compound. The Yanks applauded him: ‘that cheered me up no end.’

Green felt something ‘was up’ when their food suddenly started to improve. The stop-start negotiations had begun again (they had dragged on and off since July 1951). An Armistice was at last signed in July 1953. When the Camp Commandant told them it was all over, they didn’t believe him.

Clough never talked to his Dad about his time in captivity, conscious that as a prisoner of the Japanese in the Second World War his father had endured much worse, ‘but we understood each other’.

Norman Mounter returned safely, married Sylvia June Ross in 1959 and they had two sons and a daughter. I am aware I have intruded into their family history, but if any of them should read this, I would be pleased to hear from them. For the moment, the last few words go to Norman’s nephew, Russ Evans. Norman “could not work inside because of his experiences as a POW, which is why he became a park keeper. He was a lovely man but I now realise he suffered from PTSD which explained his quirks.”

I wonder if Norman experienced the Kennel Club? He died in 1992.

Korea remains divided.

Notes

The stand at the Imjin River led to the regiment gaining the nickname ‘The Glorious Glosters’.

Two VCs were awarded for the Imjin River:

Lieut. Philip Curtis VC, led a desperate counter attack on Castle Hill to regain a key position which had been lost to the Chinese. Under a barrage from the enemy machine guns and despite being wounded in the first attempt, he returned for a second. Moments before he was hit, he threw a grenade which destroyed the enemy bunker and machine gun. He died instantaneously. His medal was posthumous. He was 24 years old, a reservist, and a widower, with a young daughter. For the full account see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Curtis

Lieut. Philip Curtis VC, led a desperate counter attack on Castle Hill to regain a key position which had been lost to the Chinese. Under a barrage from the enemy machine guns and despite being wounded in the first attempt, he returned for a second. Moments before he was hit, he threw a grenade which destroyed the enemy bunker and machine gun. He died instantaneously. His medal was posthumous. He was 24 years old, a reservist, and a widower, with a young daughter. For the full account see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Curtis

Lieut-Col. James Carne, VC . received the award for outstanding leadership. With his Battalion under constant attack by vastly superior numbers and under heavy fire, he moved about his men giving confidence and the will to resist, personally leading two assaults. He was with the 700 on the long march to the POW camp, but was separated from them on arrival. He was tortured, on some occasions with drugs, and spent 19 months in solitary confinement. During this time he sculpted a little Celtic Cross from volcanic rock, largely by using a nail. The famous cross now hangs in Gloucester Cathedral.

There are of course many excellent accounts of the battle online written by those far more qualified in these matters than me. This article only scratches the surface in trying to convey what it must have been like for Norman, a young lad caught up in a faraway war.

I recommend the Soldiers of Gloucestershire website. This organisation can research individual soldiers for a fee, but there is a waiting list. I hope to visit the museum soon.

David Green, ‘Captured at the Imjin River’. Dave died in Australia in 2007.

Tom Clough’s account is on the ‘Blind Veterans’ website; I have been requested to share the article. It conveys the full visceral story of blood and guts. Do read it if you can.

I also recommend my favourite, the National Army Museum.

References

[1] David Green, ‘Captured at the Imjin River’. He comes across as a bit of a Jack-the-lad. Hereafter ‘D.G’.

[2] Tom Clough, hereafter ‘T.C.’

[3] D.G.

[4] T.C.

[5] D.G.

[6] T.C.

[7] anon

[8] T.C.

[9] D.G. The text says ‘gym shoes’ but I’m willing to bet Dave said ‘daps’ as we all do. His editor probably said ‘what’s that?’ and amended it. The fact that he took particular notice of their feet shows he must have still been lying down.

[10] Out of 10,000 US Prisoners, only 4,000 returned home.

[11] It is now available in health food shops, but probably in a more refined version.

[12] D.G.

[13] T.C.

Leave a Comment