In 1988 Australia celebrated the bi-centenary of the arrival of the First Fleet to Botany Bay.

I cannot claim an exact relationship with the late David Pillinger of Tasmania, and his direct descendant, a Bristol street urchin called James but I shared with them my maiden surname. David, with whom I enjoyed a sparkling pre-email correspondence more than 30 years ago, (Oh those air-mail letter whizzing to and fro!) once told me that in Australia in former times, to have a criminal forebear was something to be hushed up, but ‘nowadays’, he went on, ‘to have one convict in the family is considered laudable but to have three’ – as he did – ‘puts me on some kind of pedestal!’ In fact the murky origin of young James, transported in 1791 for the theft of a watch, had been carefully hidden and then forgotten. Until relatively recently his family believed that he had been an adventurous free-settler! A subterfuge not hard to understand when in the 19th century, another descendant became a politician, a Minister in the Tasmanian Parliament, where our surname persists in street names and an abandoned township.

At the age of ten, James, David’s four times great grandfather was living on the streets of Bristol, where he was one of gang of such boys led by Shusanna (or Shuke) Milledge, a young woman from St George, who was about a decade his senior, They were destined to meet again in Australia where both were removed during his Majesty’s pleasure at different times, James via the ‘Pitt’, Shuke by the notorious ‘Lady Julian’. In the course of unravelling their story it was a revelation to me that such rekindling of acquaintance among ‘the lags’ was not at all unusual.

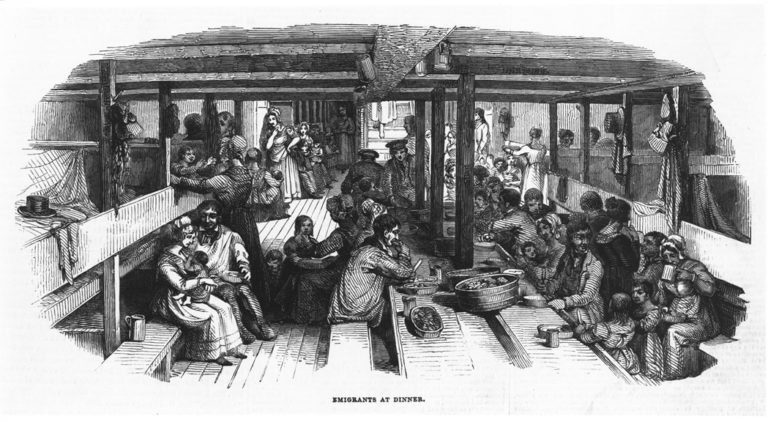

Convict women like Shuke have a bad press. According to popular mythology the transport ships were loaded with the very worst of Britain’s womanhood, often portrayed as drunken prostitutes. This is misleading, for though Shuke herself was described as ‘a lady of easy virtue’ – perhaps not without cause – the largest class of the women on the ships had been employed as domestic servants. Women were transported in the main for receiving stolen goods, for the theft of clothes, other fabrics, bed linen and trinkets. In this, the offences of the Bristol women of the First and Second Fleets followed the general pattern, which included the carrying off of small portable goods with silver spoons having a particular attraction. Shuke was different; she made off with money – a considerable sum, and in such dubious circumstances that I believe she may have been an exception to the general rule.

Apart from one woman who sailed with her two teenage daughters, the Bristol women of the early transports were older than their male counterparts, the majority of the latter being in their teens and early twenties when convicted. Once they arrived on dry land – not a given – as many convicts died during the long passage, nearly all of our Bristol women found partners, if not actually romantic love. It was not difficult to find a mate, for men outnumbered women in the new colony by at least four to one. Not a few of the women were taken up, if only temporarily, by the marines who were there to guard them.

Transportation of criminals to Australia, which lasted for more than eighty years, came about as a direct result of the loss of Britain’s trans-Atlantic colonies in the American War of Independence 1775-1783. Prior to this seismic event, America had been the dumping ground where Britain relieved herself of convicts. Between the late 17th and early 19th century there were some 200 crimes for which the death penalty was deemed appropriate. Many of these crimes, usually against property, and designed to protect the ruling class, were trivial. The words ‘death recorded’ routinely written beside a name in penal records, has led to misunderstandings among lay people (and even a notable historian) concerning the number of those who were executed. The dread sentence, though pronounced in court, with the ritual of the ‘black cap’, was carried out in less than a quarter of cases. Those reprieved received ‘a pardon’ on condition of banishment ‘beyond the seas’ geberally for a period of seven or fourteen years. The convicts were carried by ships hired by the government from private entrepreneurs. Once in the colonies, they were sold into indentured servitude often to plantation owners. It is not hard to imagine that when their time expired some were elevated to positions as overseers of the Africans who were enslaved for life.

With the end of the war, the newly independent America declined to accept any more British flotsam though African slaves continued to arrive in large numbers.

In Britain one of the lesser results of the bloody nose the country had received was a socio-economic headache. What was to be done with the convicts who languished in the overcrowded gaols?

My interest in the vast subject of transportation to Australia which followed from the discovery of James and Shuke and the other members of her gang became a series of lectures at Bristol University in 2005 from which this piece is adapted.

Chapter 1: Two Mutinies: a Horrid set of Miscreants – explains how the system of transportation to Oz came about, loss of American colonies etc

Chapter 2: The Inmates of Bristol’s Newgate Prison – how the cons waited for years in gaol or hulks, whilst the govt got the new system going.

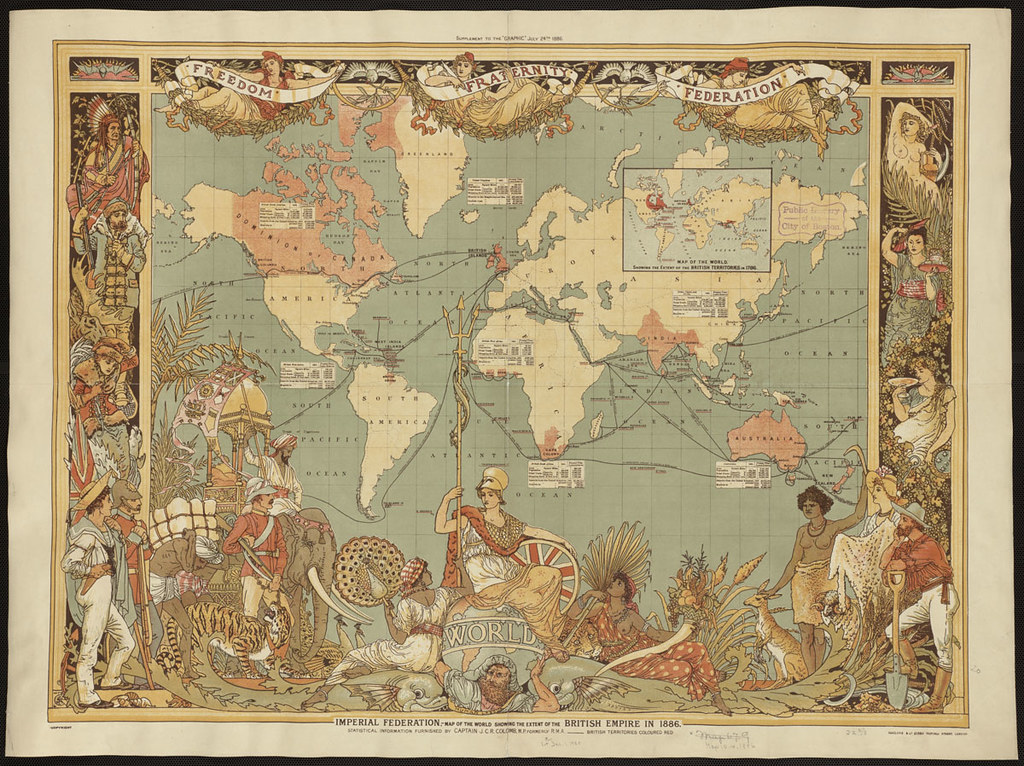

Title image: “Imperial Federation, map of the world showing the extent of the British Empire in 1886” by Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the BPL is licensed under CC BY 2.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/24528911@N05/2710800068

Leave a Comment