I love synchronicity. The story of how I was given my treasured drawing of the Five Collier Boys was at that very moment in preparation and not quite ready to go up on the website, when out of the blue I received an email, “a slightly random request” from a lady called Belinda Harding. Sorting out the contents of an old cardboard box, she found a metal plaque, about 13 inches long and seven inches wide with the legend “Manufactured by Lysaght’s Bristol”. She wondered about the history of the item.

DP Lindegaard (and Tiger Lily) with a Lysaght’s plaque

My eyes were round as gob stoppers.

Belinda, to whom I am very grateful, is one of those lovely people who don’t just throw out something which means little to them, but are curious enough to make enquiries about it.

At one time, everybody in Bristol would have known Lysaght’s, but the firm became personally familiar to me when I was doing the research for “We Shall Remember Them” my account of Brislington and St Anne’s in the Great War. I wrote:

“John Lysaght & Co normally received their supply of zinc from the Belgian city of Liege, and thus production was immediately affected when war was declared. A mass meeting was called on the morning of 7th August 1914 at the Netham Works when the management told the workforce (about a thousand strong) that they were being put on short time. The reaction of the men was startling. There were no grumbles, no rancour; instead they broke into cheers crying “Hurrah for King George and the Allies!”

“Many who attended the meeting were so overcome with patriotic zeal that they immediately joined Kitchener’s New Army so that the company was left very short staffed. Those who remained were kept at full stretch until the end of the war.”

One of the Lysaght men who immediately joined up was John Lambert of Repton Road, Brislington who came through the war. Another who survived, though his brother was killed in action, was Roland Tottle, of Birchwood Road, a clerk at the company. Others of their workmates were not so lucky. Freddie Jago*, a galvaniser, was killed at Ploegsteert, 1915; James Holman, Arlington Road, Thomas Bull*, Sandringham Road, James Reed, all died at the Somme, 1916. Tom Thatcher*, Newbridge Road, (whose father and two brothers also worked at Lysaght’s) was also killed the same year at the Somme. Henry Ricketts and Harold Leslie Jones, Grove Park, (whose father was a galvaniser at Lysaght’s) died in 1917; Albert Green*, “a potman at a galvanised iron works” (whose father and brother worked for the company) died at the Somme also in 1917.[1]

Joseph Carter, of Brooklands, Kensington Hill, died at home in November 1917.

“He had been works manager of John Lysaght Ltd, for 33 years, and in his spare time, treasurer of the Brislington Rifle Club. At the outbreak of war in 1914, Brislington’s Rifle Ranges had played a vital part by encouraging our young men to become sharp-shooters in defence of ‘King and Country’.”

Among other company employees killed in action who lived in places other than Brislington are T.H. Bennett, and Frederick Batson, 1916; Private S.G. Phipps, Gunner W. Crook, Lieut Arthur S. Richards, and Pte H.J. Godwin, all in 1917.

Sgt Dick Low

Sgt Dick Low of the 6th Gloucesters was recommended for the DCM in 1915. Harold E. Gillman of the Royal Field Artillery (one of the 14-ers, who joined up when war was declared in August) was awarded the Military Medal in 1917 for rescuing one of his gunners under heavy fire.

When doing the research I visited not only the churches and chapels of the two villages, but also sought War Memorials raised by individual firms. The firm is long gone, but Lysaght’s former HQ, a very flamboyant building known locally as “the Castle”, though formally described as “Byzantine” is still part of the landscape at St Philip’s. Other organisations have premises there now. My enquiries at the desk drew a mystified blank – not everybody is interested in history. Eventually after more detective work, I located Pauline Luscombe of Barton Hill History Group. Pauline had found the Lysaght’s Memorial tablets in the little storage building at the Avon View Cemetery, in her own words, “not being treated very respectfully”.

“The Castle” at the Netham

Within the first month of the war with 25% of the workforce absent, Lysaght’s commissioned a Roll of Honour. By 31st December 1914 fifty four were listed killed, wounded, prisoners of war or missing. In 1916 by which time the book had been published, 2,114 of their employees were serving with the Colours.

Have any of these “Roll of Honour” books survived? If so, please let me know.

After the war, Lysaght’s continued to make the local newspapers, with obituaries for long serving employees being a feature as well as other news. In the year 1939 alone, in a non-exhaustive list, James Marsh, of the sawmills, Theodore Iles, superintending engineer, and David Morell had served the company for 50,  47 and 35 years respectively. The employees appear to have had a whip round whenever a death occurred in their ranks and I spotted acknowledgements of these tributes from the families of Charles Chapple and Walter Finch. His service to Lysaght’s was mentioned when Fred Oaten was married in Australia – he had emigrated all of fourteen years before! On a tragic note an altercation between a foreman, Harry Waldron, and a younger man, led to Waldron’s death when he fell from scaffolding. As a punch appeared to have been thrown, the other man was charged with murder, later reduced when he pleaded guilty to manslaughter, receiving a short sentence of three months in gaol.

47 and 35 years respectively. The employees appear to have had a whip round whenever a death occurred in their ranks and I spotted acknowledgements of these tributes from the families of Charles Chapple and Walter Finch. His service to Lysaght’s was mentioned when Fred Oaten was married in Australia – he had emigrated all of fourteen years before! On a tragic note an altercation between a foreman, Harry Waldron, and a younger man, led to Waldron’s death when he fell from scaffolding. As a punch appeared to have been thrown, the other man was charged with murder, later reduced when he pleaded guilty to manslaughter, receiving a short sentence of three months in gaol.

Cast Iron Verandah Column, 1889, seen at Simonstown, Western Cape, South Africa.

Lysaght’s exported all over the world.

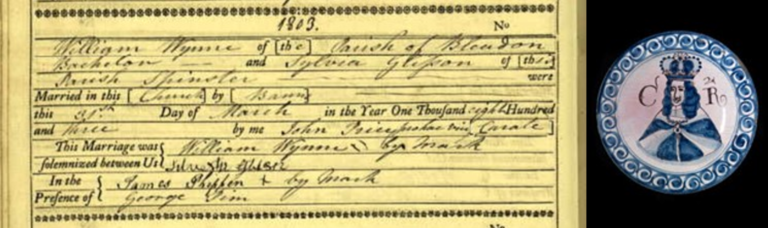

John Lysaght was an Irishman from County Cork, born in 1832, who attended school in Bristol. He acquired a small hardware galvanising business from the Clark family which he named John Lysaght Ltd. His first premises were at Temple Back but in 1869 he purchased the Netham site. By the 1880s, 400 men produced 1000 tons of galvanised sheeting a month. After Lysaght’s death in 1895 his nephews, Sydney and William Royse Lysaght took over the reins. W.R. supervised the expansion whilst S.R. became locally well known as a poet and novelist. The company, which later had works at Newport, South Wales and Scunthorpe as well as Bristol expanded into construction and exported prefabricated buildings all over the Empire and the world. It dispensed with bought in steel by opening Normanby Ironworks at Scunthorpe, Lincolnshire which produced 6,500 tons weekly which was shipped to Newport for rolling. The Newport ironworks had 42 mills, driven by six steam engines, and the works’ chimneys were a major landmark. The Lysaght family sold most of their shares in 1919 whilst retaining control in various branches. In 1920 Guest Keen & Nettlefold acquired the company including the works at Bristol, Newport and Scunthorpe. The name “John Lysaght” was retained by GKN for its works at Newport and Scunthorpe and was still in use until 1966 at least.

Belinda is puzzled how she came by the plaque. She has an idea it might have something to do with the railway: before Dr Beeching wielded his deadly axe, the London to Bournemouth line crossed the farm where she lives. There is a ‘Crossing Cottage’ where the gates across the railway line were situated and you can still see the remains of the railway sleepers in places. As “railway goods sheds” were among Lysaght’s specialities, as confirmed by the above advertisement, this possibility may be correct.

To end as I began: I have a confession to make. Belinda wondered if her plaque would be of interest to a museum or other such organisation. I suggested a few likely places but avarice got hold of me, and cheekily said I would like to have it myself. Belinda very kindly donated it to me. I am incredibly grateful for her generosity. Though it seems possibly of a later vintage, I look upon it as an “In Memoriam” to those Brislington men and boys who were killed in action and the many others who I don’t know, but are also on Lysaght’s War Memorials. I hope to add the subject to my list of “talks” to various groups once we can all meet again in person; I will use the plaque and this story as another “show and tell”, though I can’t guarantee my son will take part as a galvaniser, corrugated or otherwise!

Acknowledgement: With many thanks to Belinda Harding

see https://www.gracesguide.co.uk/John_Lysaght’s_Bristol_Works

[1] Those with an asterix * are named on the Lysaght War Memorial.

Blog Comments

Belinda

25th September 2021 at 3:07 pm

I do appreciate Doreen’s kind words and am just so pleased that the plaque has found such a good home!