A few years ago, an emailer to my website asked me to help find her Jewish ancestor who lived in Bristol. Alas I found nothing on the lady’s particular family, but after a few experiments with google, I chanced upon the history of another Jew, who lived in our city in the 16th century. It appears that Jews were tolerated as long as they kept quiet, but one…….

……..“who failed to keep silent when necessary was Joachim Ganz, a Bohemian mining engineer.”

Ganz, also known as Gans, was born in Prague and first turned up in Cumbria in 1581. He introduced a new process for the “making of copper, vitriol and the smelting of copper and lead ores.” His most dramatic discovery was to reduce the time it took to purify a batch of copper ore from 16 weeks to just four days. A skilful all-rounder, he used the impurities removed from the copper ore to make textile dyes. He travelled to America with Sir Walter Raleigh and was in North Carolina in 1585 with Sir Richard Grenville. Amongst the ruins of the settlement among archeological remains there are lumps of smelted copper and a goldsmith’s crucible, supposedly the work of Ganz. When the Royal Mining Company failed to re-supply the colonists, and they became increasingly fearful of attacks by the local native American population, they, including Ganz, returned to England in 1586.

Now Ganz seems to have been abandoned in Bristol where the powers that be neglected to make use of his unique scientific talents and he had to eke out a living giving Hebrew lessons to pious gentry who wished to read the Old Testament in the original. In 1589, he came to the notice of Richard Curteys, the Bishop of Chichester, who arrived hot-foot to make enquiries. Ganz, speaking “in the Hebrue tonge” admitted he was a Jew. He was now treading a very dangerous path.

“Do you deny Jesus Christ to be the Son of God?” asked the Bishop.

Ganz replied, “What needeth the Almighty to have a son? Is he not almighty?”

The horrified cleric recorded that Ganz “did not believe an article of oure Christian faithe, for that he was not brought up therein.”

He reported the matter to the Mayor and Aldermen of Bristol who were likewise scandalized. They sent Ganz to London for examination by the Privy Council. We can imagine he was not treated gently. Though burning at the stake for blasphemy was not as common as it had been in the reign of Mary I, it was on occasions used by her sister Elizabeth as a deterrent. There is no evidence that the ultimate sentence was carried out on Ganz, (though as I frequently remind myself absence of evidence is not evidence of absence) and there is a marginal hope that powerful friends in the Royal Mining Company may have interceded on his behalf. I cannot believe he was let off altogether. Perhaps he died miserably in prison. Whatever the truth of it, he seems to have disappeared from the annals. I can’t help thinking that the blinkered officials, not helped by the busy-body bishop, may have missed an opportunity. What if they had made better use of Ganz? What if the Industrial Revolution had arrived in Bristol two centuries early? Might we have solved “climate change” by now?

Notes

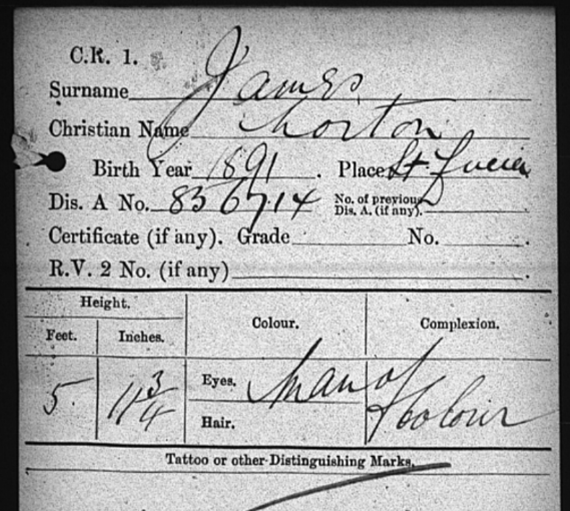

The picture used is a portrayal of another Jewish man, a contemporary of Ganz, Dr Lopez, executed in 1592 for an alleged plot to poison Queen Elizabeth I.

This article previously appeared in a SGMRG Newsletter ca 2013/14.

Leave a Comment