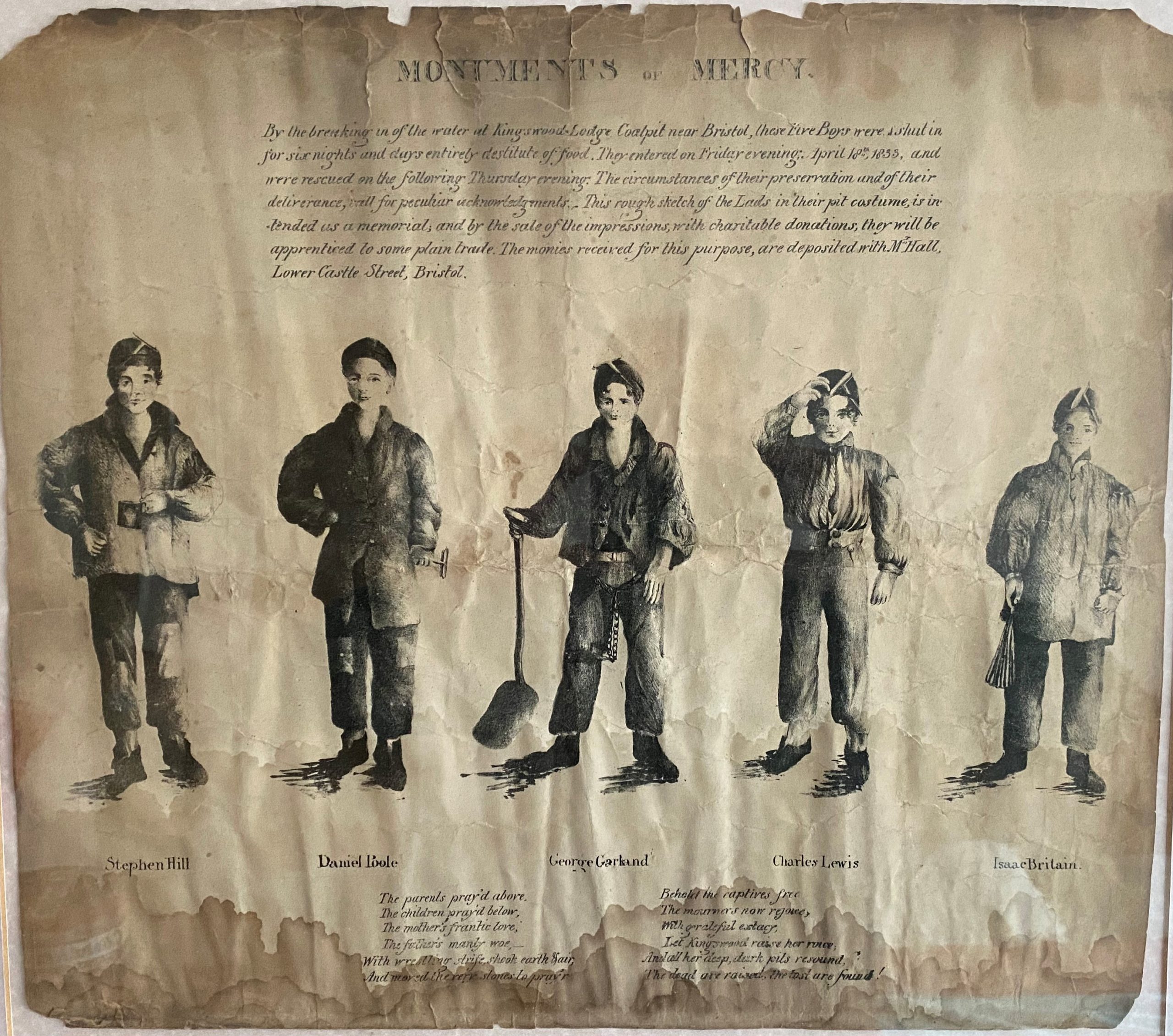

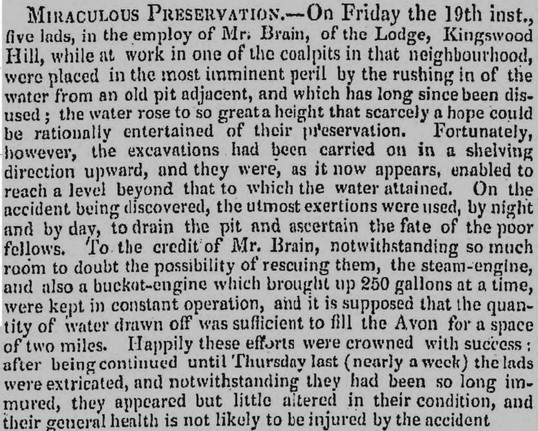

On pages 126 -127 of my book, ‘Killed in a Coalpit’ there is a picture of five young colliers named Stephen Hill, Daniel Poole, George Garland, Charles Lewis and Isaac Britain. They were entombed in Lodge Pit, Kingswood in 1833 for six days and nights, but miraculously rescued alive. The incident aroused a certain amount of compassion in the Bristol townspeople and a sketch, drawn from life, but not particularly well (the artist could not draw hands!) was reproduced on paper and sold, as it is alleged to apprentice the boys ‘to some good, plain, trade.’

One copy of the drawing was on the wall of the corridor at my alma mater, Kingswood Grammar School, though nobody paid much attention to it. In any case, It was lost forever in the conflagration which in 1976 razed the old ‘cowsheds’ (as the school was affectionately known) to the ground. Anyway, ‘ordinary people’ didn’t have a history, did they? History, writ large, which we were taught was about royalty, politics and wars, where great white men did great things, and almost all were men apart from Boadicea (as was), Queen Elizabeth I and Florence Nightingale, Not a word about our ancestral cannon-fodder, blood-spattered and heavily reduced by pit accidents and judicial murder. After a brief flurry of interest in the 1890s by the antiquarians, Braine (Kingswood Forest) and Emlyn-Jones (Mangotsfield), by the 1950s, only one person appeared to be writing about the area, Dorothy Vinter[1], the doctor’s wife, and though the green shoots in my history garden were already poking through the ground, I was too timid to approach her. Mrs Vinter mentions another copy of the drawing (which, if I remember rightly) was in the hands of Mr Graham Bamford of the ironmongers in the High Street, I have never been able to track him or it down. This leaves just one other copy. And it is MINE. As far as I am aware it is unique: the only survivor of the print run of 1833.

When I began my “real history” in earnest – you do need the framework of the big stuff for context, so I won’t knock it – it was the 1970s. I wrote to the newspapers for remembrances of my coalmining forebears and their mates, the ancient coalfield where they ‘wrought’ for centuries having been all but forgotten, its relics mostly obliterated. One of the replies came from a “W.F. Lloyd, (Miss)”. This lady said she did have something which might interest me, but not to get my hopes up, as, really, it was not much good, it was very old and tattered……This did not sound too promising, but I made arrangements to call and see her. Miss Lloyd, (I never called her by any other name) produced a completely flat package about 20 inches square wrapped in brown paper. She carefully undid the string and stripped off the protecting sleeve and I gaped in awe at the five young faces which stared back at me. The dear lady continued to apologise for the state of the picture, evidently mistaking my trembling excitement for dismay.

“It looks dirty, but that’s the damp stain, and it is old, after all,” she said. “For many years it hung in my uncle’s pub at Hopewell Hill. I don’t expect you will want it…….”

“Want it?” I cried. “I love it!”

“Then you must have it,” she went on, beaming now. I mumbled something about it being a valuable treasure, a half-hearted protest she dismissed at once.

“It’s like this, my dear,” she continued. “I’m the last of my line, and when I go this place will be gutted out. An old picture, just a thin, stained bit of paper, it will land up on a skip, if it’s not destroyed altogether. I want you to have it, as you know what it is…..and will value it.”

I felt uncomfortable, not being in the habit of relieving elderly ladies of their property, but in the end, I accepted the picture, but on “extended loan” saying that she could have it back any time. My Mum and Dad were still alive, so I was in Kingswood fairly frequently. I walked down to see Miss Lloyd at New Cheltenham a few times. “I’ve still got your picture!” I would say blithely. “Good,” she would reply, pleased, and eager to show me her latest successful specimen of flowering cactus. If I didn’t visit I would phone, but often the days and months slipped by faster than I noticed. I would have a twinge of conscience and realise it had been sometime since I made contact. On the last of these calls there was the continuous whine of a discontinued telephone line. Via the library (no data protection then) I was able to obtain the name and phone number of one of her neighbours. I was told that my kind benefactor had died suddenly and had already been buried.

Miss Lloyd (who had told me her ancestor was Stephen Hill, one of the boys) was the only child of Frederick Charles Lloyd, a tailor’s cutter and Fanny, nee Shepherd. When counted for compulsory war registration in 1939, aged nearly 31, she lived at home with her parents at Chester Park, Bristol. She worked as a wages clerk in the offices of a coal merchant. I was glad to know of the vague connection with coal, but it gave me greater pleasure that in that fearful year, she was prepared to do her bit as “Air Raid Warden DKBI attached to Bristol Constabulary”. Miss Lloyd died on the 23 February 1979 aged 70.

The picture, now beautifully framed, is on a wall in my house. I do value it and look at it often, remembering the circumstances in which it came to me. Call it luck, or Providence, but I believe I was meant to have it. I was young-ish when I first met Miss Lloyd and at that time she seemed quite old to me. Now that I am older than she was, I feel I can call her by her given names, and say with respect, “Winifred Frances Lloyd, thank you. May your generous spirit rest in peace.”

There is a sequel to the story of the picture. My son Kevin, 6 feet four inches tall in his socks was once a small boy. He writes:

“When I was under 10 years old, Mum would dress me up as a little miner and take me around to local history talks as a show and tell. Unfortunately there are no snaps to record these events, we didn’t have a camera at the time, but I would have looked something like the boys in the picture. I would be wearing very old clothes, coal dust streaked on my face, with an iron chain round my waist (a ‘tugger’) and a miner’s iron T-shaped candle stick (a real one) stuck in my cap. For the sake of authenticity Mum would light the candle. The audience would “ooh” & “aah” in sympathy. Once in a while one of the ladies who frequented such events would push a 5p or 10p into my hot little hand! My sisters were mad as hell – of the monetary aspect – but as Mum said, strictly adhering to historical accuracy, “Only little boys worked in the Kingswood mines. No women or girls at all.”

[1] I hadn’t then heard of my not-quite alter ego, Mr Sanigar who wrote about St George.

Leave a Comment