Harriet’s Story

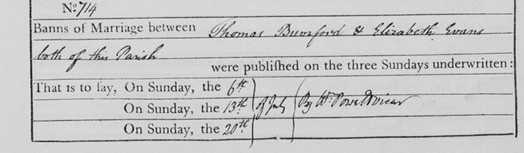

Thomas Bumford and Amelia Evans were married on 3rd August 1828 at Abergavenny, a small Welsh market town on the river Usk about six miles from the border with England. This is stated as fact on a great many on-line family trees, though in transcription form and I have not seen the original document. A copy of the banns of marriage called at Abergavenny Parish Church on 6th, 13th and 20th July is reproduced below. “The banns” – the naming of those intending to wed would have been read aloud to the congregation on those three Sundays. If anyone knew of “a just impediment” to the match, they were exhorted “to speak now or forever hold their peace”. Even with my poor eyesight I can spot an anomaly. If Amelia was the bride, then her banns were called in the wrong name!

The couple were very young, in their late teens, but at least Thomas had a trade; he was a plasterer. By 1830, Thomas and Amelia were living in Monmouth where several of their children were baptised at St Mary’s church. The first of these was Emma on 18th September that year; sadly she died at just over twelve months old and was buried on 4th October 1831. It is possible that Harriet was born the same year but owing to the grief of the bereavement her baptism was overlooked. The next child in the register, Thomas junior was baptised on 3rd June 1833, followed by Edwin, 18th January 1837 and Alfred Joseph on 1st May 1839.

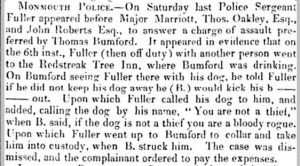

On 6th July 1839, the children’s father Thomas Bumford who was drinking in a pub, the Redstreak Tree Inn, was involved in a skirmish with an off duty Police Sergeant, Ps Fuller of the Monmouth Constabulary. It could be surmised that Bumford and Fuller had crossed swords before, apparently over the Sergeant’s dog, which was the subject of obscenities hurled by Bumford at the other man. Following the altercation, the context of which is not explained in the newspaper report, Fuller attempted to arrest Bumford, who struck him. Conversely, it was Bumford who brought a charge of assault against the policeman. The case was dismissed with costs issued against Bumford.

Monmouthshire Beacon, 27.7.1839

By 6th June 1841 when a census was taken, the Bumford family had moved to Bristol. Thomas was recorded at his workplace, Guinea Street, along with other plasterers, carpenters and labourers engaged on an extension to Bristol General Hospital which had been originally established in 1832 in a small house in the street. The head of the household is shown as Robert Norton, 25, a surgeon, who was resident along with a matron and a number of nurses. Presumably the patients had been transferred to Bristol Infirmary to escape the dust, noise and general mayhem of the building works. Thomas Bumford’s wife and children lived about a mile away, along the Harbourside and up a steep hill to a tenement at Jacob’s Wells in Clifton. Amelia, wife and mother, “married, aged 33”, gives the answer “Yes” to the census question “Were you born in this county?” (i.e. Bristol or Gloucestershire). For her children the answer is correctly stated as “No”. As we are aware they were born in Monmouth. For the first time, in this mean dwelling, we meet Harriet, by then twelve years old. Thomas junior is eight, and after him comes Joseph, aged 6, another whose baptism was apparently missed, then Alfred Joseph, 2, and the latest arrival, a new baby, George Albert, aged three months. Edwin is missing, not dead as might seem possible, but left behind in Penallt, Monmouthshire, a ‘nurse child’ aged four, in an oddly assorted household consisting of James Robbins, a fifty year old stone cutter, Mary Evans, aged 70, and Mirah Cutter, fifteen. (Evans is obviously a common surname, but Mary may have been Amelia’s mother.)

In 1843, a daughter Selina Emma was born. The next year the little boy, George Albert, died at the age of three. In 1849, Harriet makes her first appearance in the news, a year which coincides with the family in mourning for yet another child, ten year old Alfred.[2]

The Bristol Times and Mirror of the 4th August 1849 states that Harriet Bumford was……

“…… charged with stealing clothes, the property of her father, Thomas Bumford. This day fortnight, the prisoner, during her mother’s temporary absence from home, stole £2 worth of bed and other clothing and pledged it all with various pawnbrokers. She committed a similar offence some time ago when her father forgave her, and continued to maintain her, although she was nearly 19 years old; but he said, she had always behaved ungratefully for kindness. The prisoner was remanded for the production of further evidence.”

A further instalment appears in another part of the same paper:

“Harriet Bumford remanded from yesterday on a charge of stealing wearing apparel &c., the property of her father was, together with Elizabeth Dowling since arrested as an accomplice, again placed at the bar. The evidence against Dowling was that she carried away a bundle of clothes entrusted to her by the other prisoner. The magistrates asked the father of Bumford if he wished to prosecute and he replied in the affirmative, as it was the only chance of her leading a better life; she had been taken out of a brothel and he would rather she went to gaol than continue to go on so. The prisoners were further remanded as some of the property remains to be traced.”

In the event, Thomas Bumford changed his mind, and declined to prosecte his daughter, so the case against the two girls was formally dismisssed.

In March 1850, Harriet was in trouble again. Described as “a girl well known to the police” she was charged with the attempted theft of a workbox, the property of “her aunt, Harriet Lane.”[3] A little girl deposed seeing her about to commit the offence, but she was disturbed before she succeeded. The magistrates ordered her to be committed for three months to hard labour: upon which she said, truculently,

“I don’t care for three months. I wants it longer. I and another girl stole a watch and pawned it at Bath, and if you remands me you can send me down on the Cut for that.” [4]

Harriet’s broad Bristol accent together with its idiosyncratic grammar is still recognisable, and can still be heard on occasions in the City today.

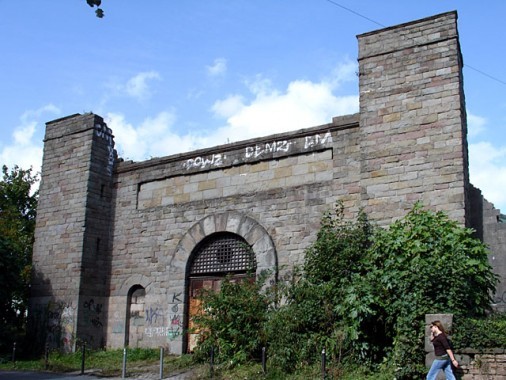

By “the Cut” Harriet meant the new Gaol in Bristol’s harbour, where a few months before a nineteen year old servant girl had been publicly hanged for the murder of her mistress.

The ruined gateway is all that remains of the Gaol today. (photograph copyright, Linda Bailey)

Harriet was removed to custody to serve her sentence in the Gaol. With her time expired, she was released, but after a few days, or even hours of freedom, she was charged with another offence. Described as

“a violent character who spends the best of her time in the Bridewell”[5] she was accused of assaulting her father.

She “earnestly pleaded her own cause and accused her parents of driving her by ill-treatment to the vicious life she was pursuing.”[6] The parents, who were in court said they wanted nothing more to do with her.

The Bench confessed themselves “in a fix” as what to do about Harriet. It seems that despite everything they realised she was a very troubled young person. Thirty, or even twenty years before she would have been an automatic candidate for transportation to Australia. At last they decided to fine her 10 shillings plus costs, or fourteen days imprisonment in default. Harriet promised that if she could get her clothes out of pawn, she would leave Bristol and endeavour to get a situation elsewhere. As the girl had no money to pay the fine, Mr Brice, an official of the court, said that if she behaved herself well during her confinement the Governor of the Bridewell would perhaps be able to help her regarding the release of her clothes.

Unfortunately, Harriet’s promise came to nothing. On 2nd November she was sentenced to two months for stealing a gown belonging to a certain William Smith. Could this have been because she had been unable to redeem her own clothes?

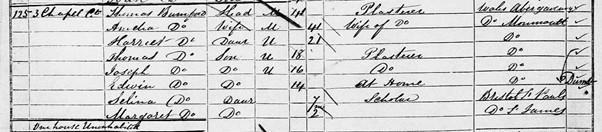

In 1851 it seems that her parents had relented. In the census of 30th March that year they were all at home, 3 Chapel Street, St James. Thomas and Amelia were both aged 41, Thomas hailing from Abergavenny, Amelia and the older children including Harriet, now 21, born in Monmouth.

The entry is beautifully clear, but the census taker was slightly confused as to which person was handicapped. In fact he was right first time. It was Edwin, the toddler who had been left behind in 1841, who was “dumb,” as recorded in the blunt, insensitive manner the Victorians adopted in labelling those with disabilities.

Harriet did not remain with her parents long. She may have already met the man who would become her husband. Frederick Alfred Darke, usually known by his second name, a butcher, born in Taunton, Somerset. Both parties were 23 when they were married at St Jude’s on 30th January 1853. Alfred signed his name. Harriet marked with an ‘X’. The witnesses, who both signed, were Alfred William Bosher, and Sarah Bumford, Harriet’s new sister-in-law, recently married to her brother Thomas.

In June 1855 Harriet Dark [sic] was taken to court for assault by Mary Anne Beechy; a fight allegedly broke out between the pair caused by Harriet’s envy of the other woman’s silk gown. Both appeared in court the worse for wear, bearing the marks of the battle. The magistrates found the case proved, that Harriet had struck and bit the complainant and that the injuries she herself sported were largely provoked by her own violence. She was fined five shillings plus costs, with the usual seven days imprisonment in default. Whilst depositions were being taken in a nearby room,

“the prisoner amused herself with a game of fisticuffs with a couple of the officers to one of whom she dealt a severe blow in the face.”[7]

At the census of 7th April 1861 Harriet and her husband, now known as Alfred were living at 24 Penn Street, St Paul’s with their young son, called Thomas William, born 1858, by then two years old.

Meanwhile, Harriet’s father, Thomas Bumford, age given as 54, was again away from home, this time at Hound, Hampshire where he lived in one of dozens of huts occupied by building workers engaged at the Royal Victoria Works. Thomas was crowded in with other men in ‘No. 10 hut’. It would have been very rough and ready, cold and dirty, with few if any amenities. Tom Bumford seems to have specialised in hospitals: this site would become The Royal Victoria Military Hospital.[8]

By 1861, Thomas Bumford junior, a plasterer like his father, who had been married in Bedminster1853 to Sarah Forse were the parents of a young family of four sons, Thomas, Joseph, Edward and the baby, Alfred, just one month old. His mother Amelia shared their premises at 20 Water Street, St Paul’s, along with her children, Emma aged 12, Margaret, 10, and Edwin, aged 24. Edwin was again described as ‘dumb’ and seems to have been unemployable.

(There was a “Deaf and Dumb School” in Orchard Street, a small privately run institution dependant on charitable subscriptions. It is unlikely that the Bumfords could have afforded to send Edwin there. Civic provision for the education of the deaf did not commence in Bristol until the 1880s.)

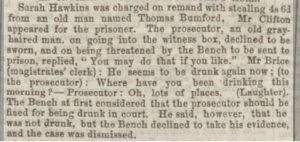

Edwin’s sister, Selina Bumford had apparently died pre 1861, though her passing seems not to have been noted anywhere. Their mother Amelia would not have much longer to live; she was buried on 4th August 1861 at St Paul’s Portland Square, her age given as 54. A few weeks later, her widower made an appearance in court when a woman was charged with stealing four shillings and sixpence from him. The years had worn him down. He was only in his early to mid-fifties but the reporter described him as “an old man”.

Western Daily Press 24.9.1862 [9]

I cannot help but observe that there seems to be a pattern of behaviour in the family, including in-laws, involving quick tempers and alcohol.

With the death of his mother, the tragic Edwin became a burden which no-one could bear. He was buried, aged 27, on 8th September 1866, at Holy Trinity. Stapleton, an inmate of the Workhouse which the church served.

In October 1867, a year after Edwin’s death, the Workhouse was the subject of an inspection by the British Medical Journal:

“In the male infirmary the use of one wash-basin and one towel a week was allowed for each ward; in the female department similar arrangements existed except that there was only one basin for the use of the patients in both lying-in wards. In one of the sick wards the only basin was retained to make poultices in; a bucket serving not only for the purpose of washing the wards and the patients’ hands and faces but for any bad legs or wounds requiring such treatment, and lastly [for washing] the plates and cups. In another ward if the patients wanted to bathe any sores etc, they had to do so in their chamber-pots. All the towels were in an extremely dirty condition.” [11]

During this decade Harriet gave birth to another son, Joseph in 1862 and then a daughter, Emma Amelia in 1866. But all was not well. In August 1867 at 11 o’clock at night, she was seen and heard on Bristol Bridge threatening to jump over the parapet and drown herself. She was apprehended by Pc Legg who restrained her with great difficulty. She was charged with attempting to commit suicide which was then a criminal offence. She appeared to have been drinking and stated that her husband had ill-used her – which he denied. She promised the Magistrates she would not do such a thing again and they discharged her, possibly moved by her pitiful state. [12]

Bristol Bridge (NB. Mr Google thinks Bristol Bridge means Clifton Suspension Bridge. Wrong!)

In 1868 Harriet gave birth to twins, Clara and Alfred Darke who were baptised at St Clements on 7th September. The babies lived only six weeks. Though their address is given as ‘St Paul’s’, they were buried, ominously, at Holy Trinity, Stapleton, recorded at the same Workhouse church where their uncle Edwin’s funeral had recently taken place. Harriet had fallen on very bad times and matters were about to get even worse.

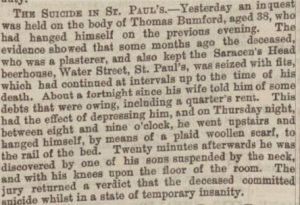

In addition to working as a plasterer, Thomas Bumford junior and his wife Sarah had added to two more sons to their family, Alfred in 1861 and Albert in 1863. In 1869, Sarah was pregnant again. In addition to Thomas’ plastering work, the couple had taken on the license of a beer house, the Saracen’s Head on Water Street. Unfortunately Thomas was not in the best of health, and recently he had suffered from “fits” which were gaining in frequency. Fits are an abnormal electrical activity in the brain which can occur quickly and in some cases result in unconsciousness or seizures, when the body shakes uncontrollably. Fits can have causes other than epilepsy, for instance stroke, or the result of a head injury. In Victorian times such seizures were believed to be the result of madness and therefore carried a severe stigma, something to be kept quiet within the family circle. It is doubtful whether Tom would have risked seeing a doctor about his condition. If this was not bad enough, he had financial problems. The couple had debts which included a full quarter’s rent which was overdue. Destitution and the Workhouse – or the insane asylum – loomed huge in his troubled state. On a Sunday evening in early July 1869, between eight and nine o’clock, he excused himself from the bar and took himself upstairs. He was in despair. He sat on the side of the bed unable to see a way out. Twenty minutes later, one of his sons went upstairs to look for him. Thomas had hanged himself with a plaid woollen scarf which he had tied to the bed rail. He was suspended by the neck with his knees on the floor. An inquest verdict was returned that he “had committed suicide whilst in a state of temporary insanity.”[13] He was thirty eight.

Western Daily Press 10.7.1869

Tragedy upon tragedy. A few days later, his father and namesake Thomas died, “aged 61” at the same address, 5 Water Street. The cause of death was given as “lung disease” (TB, the endemic disease of the poor) but it may be supposed that shock and grief also played their deadly part.

As to Harriet, if her life had ever been settled, now it descended into even more turmoil. She and Alfred Darke had separated.

(In abandoning Harriet, Alfred Darke also inexcusably washed his hands of his children. His subsequent life can be followed with ease through the censuses. He had met up with another woman, Elizabeth, and by 1871 was living with her and their two year old son at Merthyr Tydfil in Wales where he had found employment as a pork butcher. Alfred was ambitious and literate; he would have studied the newspapers for a suitable opportunity which he found in Ashton-under-Lyne in Lancashire, sufficiently far away from nosey parkers who might query their marital status. By 1881 Alfred and Elizabeth, now with three children, two boys and a girl, were installed in their own pork butcher’s shop. They would remain in Ashton-under-Lyne for the rest of their lives. If the enterprise was initially successful, Alfred’s fortunes had declined by 1891, when he is described merely as “a pork pie maker”. In the drab winter of 1895, Elizabeth died, aged 60. She was buried on the 16th February. Alfred declined still further, and in 1901, aged 70, he was living in lodgings in the house of a woman called Kate White. Despite Elizabeth’s death he still described himself as a pork butcher, and “married”. In 1905 he was among those in the town seeking Poor Relief. In 1911 he was living at 74 Moss Street, almost down and out, and making a sparse living as a “pie hawker”, but, despite his mean circumstances, he had found himself a “housekeeper”, 18 year old Beatrice Grafton. It is difficult to see the attraction, but love blooms eternal and life is always full of surprises. That same year he and Beatrice were married. They had a few years together until he was buried aged 80, at St John the Evangelist, Ashton-under-Lyne, on 9th May 1914.

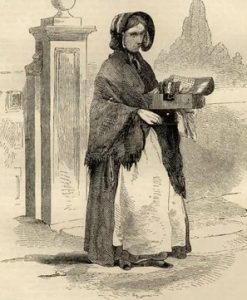

A 19th century street-seller: Harriet hawked fish around the Bristol Streets. Her daughter sold flowers.

Beatrice lived on until 1965. In 1939, when numbered for war registration purposes, she was resident in Cardiff with twenty two year old Enid May Morgan. Beside Enid’s name is another, “Alexander Darke” which is crossed out. The identity of this man – or boy – must be a whole other story.)

We left Harriet abandoned – or perhaps she had kicked Alfred out? We know from other evidence that she was capable of landing a punch or two. But it is more likely that having met Elizabeth he simply failed to return home one night. Harriet may have looked for him, despairingly? Bad mouthing him? We shall never know. The only evidence shows that on the 3rd April 1871, she was working as a fish seller and living at 16 Rosemary Street, with her three children William, 13, Joseph, 9 and Amelia, 5.

A decade later on 5th April 1881 at 4 Houlton Street, in premises which were partly a coffee shop, Harriet was now working as a laundress. This was a specific occupation, more than being a mere washerwoman. A laundress offered a full service in her own home, which could involve seven or eight stages, from fetching the dirty laundry, carrying water from a well, mending, scrubbing, starching, mangling, to drying and ironing and returning the clean clothes to the customer.[14] It was hard, back breaking work. Though the pay was very poor, only the rich could afford such a service; they would change their clothes about once a fortnight, whereas the poor usually only had one outfit of clothes.[15]

Women’s work – a Victorian Laundress

Women’s work – a Victorian Laundress

Only Amelia, aged 15, was still living with Harriet; the girl, officially described as “a bouquet seller”, made a precarious living by hawking flowers in the streets or endured abuse as she slogged door to door. By 1891 Amelia was married to Charles Watts, a mason’s labourer, and had two children, boy and girl twins who they named Charles and Amelia after themselves. Harriet’s whereabouts in 1891 are unknown. Perhaps she was homeless, down and out, just an anonymous bundle living in the gutter. Her death, of chronic bronchitis and cardiac failure, was recorded on 25th October 1895 at 4 Tippet’s Court. Had he but known it, Alfred Darke had truly become a widower, just a few months after the death of his other, informal “wife”. The informant was S. Bumford, Harriet’s sister-in-law (otherwise Sarah, the wife of Joseph) of 19 Cowley Street, Bristol who was present at the death.

Joseph Bumford and Sarah Jones had been married in Pontypool, Monmouth, in 1859; this was Sarah’s birthplace. By 1891 they were the parents of eight children, four girls and four boys. Joseph followed the family trade as a plasterer, as did his two eldest sons. Like his tragic brother, he too had dabbled in the pub trade. In 1871 he was the licensee of the Jolly Tanners in 59 Great George Street, St Philip and Jacobs, but by 1891 he had reverted to his single occupation as a plasterer.

This is not the end of the story. We shall return to the Bumford and Darke families to find what happened to ‘the other Sarah’, widowed when her husband Thomas Bumford took his own life; and then to Harriet’s children and grandchildren. The trail will take us not only across the Bristol Channel to Wales, but across the wide Atlantic to the USA and Canada and….

……..like father, like son, Harriet’s son Thomas William Darke abandoned his wife and family……….

To be continued.

Acknowledgements: I am grateful to Sue Browning of Canada for kindly sharing her ancestor Harriet with me. The picture of the street seller at the beginning is from Mayhew’s London, and filched from the wonderful website of “the Gentle Author” @thegentleauthor.

[1] Monmouthshire Beacon, 27.7.1839

[2] Birth and death certificates for these children would give further information about the family’s circumstances.

[3] The exact relationship between this “aunt” and Harriet has not been established. It could well be that the girl was named after her.

[4] Bristol Mercury 30.3.1850

[5] All houses of correction were known as Bridewells after the original, Bridewell Palace in 1553. The name still survives in Bristol as Bridewell Police Station.

[6] Bristol Times & Mirror, BTM, 27.7.1850

[7] Bristol Mercury 16.6.1855

[8] For a later era concerning exploitation of such workers, see Robert Tressell’s seminal work ‘The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists’.

[9] Western Daily Press 24.9.1862.

[10] BTM 11,10.1862

[11] On-line website, Stapleton Workhouse.

[12] Ibid, WDP, 27.8.1867

[13] WPD 10.7.1869

[14] See “The Life of a laundress in Victorian Gloucestershire”, an excellent on-line website.

[15] My own mother, born 1906, told me that her brother, trick acting one day pushed into a full bath tub. Presumably my grandmother was doing washing. She could not go to school because she had no other clothes to wear.

Blog Comments

Shu P

24th August 2021 at 7:44 pm

Indeed tragedy upon tragedy – we really have it easy now don’t we? One thing I don’t understand…. Why steal from poor relatives rather than expanding horizons to richer pickings?

dp lindegaard

25th September 2021 at 5:54 pm

The poor (I regret to say) preyed upon the poor. Easier, rather than richer pickings!

Michael Darke

6th June 2023 at 5:03 pm

Hello, I have just read this wonderful story. Harriet is my great great grandmother! my great grandfather is Harriet and Frederick (Alfred’s) second son (Thomas) Joseph. I am doing some research on my family and I didn’t know any of this. Was there/is there a sequel please I would be really interested to read it of there is? Thank you so much.