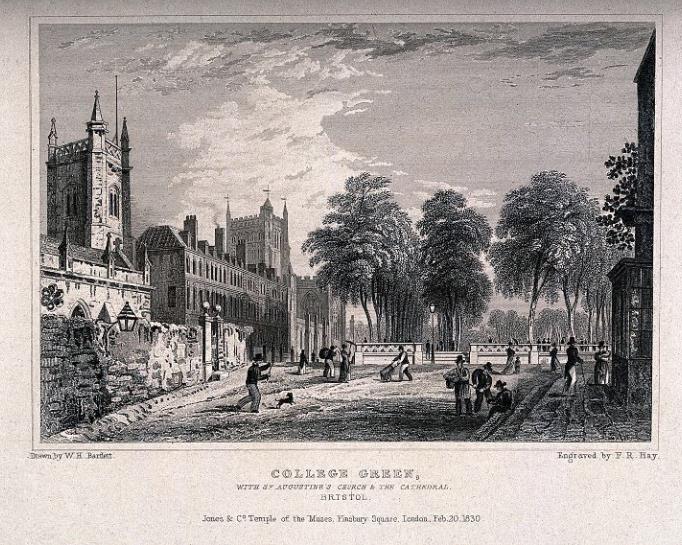

On Thursday 27 September 1764, a spinster in late middle-age, Miss Jefferies, went to her sister Frances’s house on College Green where she had been invited to dine at 12 noon. It appears the front door was not locked and the unsuspecting lady walked into a nightmare vision of gory horror. Miss Jefferies must have gone into extreme shock, and it was left to others to describe the scene.

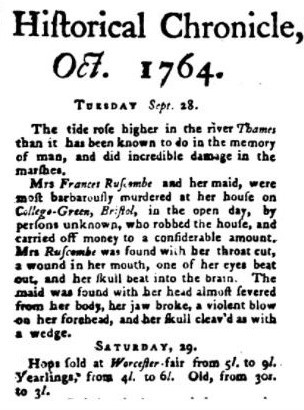

Frances Ruscombe lay dead on the stairs, her throat cut and with a wound on her head so violent that the skull was pushed into the brain. Mary Sweet, more usually known as Mary Champness, was discovered in the back parlour, her head almost severed from her body, the skull cleaved as if with a wedge. It was supposed the deed had been committed only an hour or so before; the corpses were still not cold. It was supposed the wounds were made with a hammer. After an initial inspection it was believed that the premises had not been robbed, though some things had been strewn about in confusion. All other parts of the house were secure, so the perpetrator must have gone in through the front door and left the same way. It was amazing that in so public a place nothing unusual had been observed (a blood-spattered person?) at a time when many people were about, going to and from prayers at the Cathedral. No suspicion, said the newspaper report, fell upon anyone.

The funerals took place before the next paper came out (newspapers were published once a week). Mary Champness was buried at St Augustine the Less on 30 September and Frances Ruscombe in the chancel at St Stephen’s, the 1 October.

So, originally, “nothing was taken” and “the murderer must have entered via the front door”. From the sister’s statement we can deduce that the door had been left open as she had been expected. Mary Champness, who appears to have been the only servant, a maid-of-all-work, who would have been fully occupied cooking the midday lunch for her mistress and the guest would not have wanted to stop to answer the door. Keys were large and made of iron, so it is unlikely Miss Jefferies would have carried one in her reticule. If the door had been locked then perhaps the murderer had a key. If it was habitually open this may have been common knowledge and he or she could have entered with a minimum of trouble. If the door had been closed from the inside then the intruder had been let in by either of two women inside the house. Could he or she have been in the house already? The extreme savagery involved shocked the City. (Though petty crime and violence, both criminal and judicial, was commonplace, murder seems to have been less frequent than nowadays, at least if reporting is to be believed.)

A reward was offered for the apprehension of the murderer. There was no police force in this era and the only “constables” available were those elected annually by each parish from among the top drawer of townsmen or villagers. Detective work was carried out by the likes of Jonathan Wild, the notorious London “thief-taker” who was eventually hanged himself. Informers would keep their eyes open for anything untoward and would “nose” their suspicions to the magistrates who administered the law. The surest way of finding a culprit was via a reward. In this case the initial reward offered was £100 to be paid on conviction, to which £10 was added by James Ruscombe, the murdered woman’s husband.

A week later the Bristol Journal gave more details. A preamble revised the previous facts but added a statement from Mrs Ruscombe’s sisters that the murderer(s) “went upstairs into a closet where they broke open a trunk and took out papers plus 57 guineas tied up in a bag marked with the letter “I”, a silver purse containing 36 shilling pieces and 21 guineas. This was sensational; the original report had said nothing was missing. The sisters, Elizabeth and Sarah Jefferies offered their own reward of 50 guineas, hoping to entice “any person concerned in the above except the person who committed the murder and robbery” to come forward and grass his companions.

On the third of October 1764, Elizabeth and Sarah Jefferies proved their sister’s will (made in 1762) as executrices. Frances died possessed of a rank of four houses in Host (or Horse) (?) Street which she left to her husband for his lifetime and after his death to her sisters if they survived him, otherwise the property was to go to the Dean and Chapter of Bristol. There is a peculiar clause. Frances left her husband (un-named) the sum of £40, provided he would allow the sisters to have “all my wearing apparel and cloaths” but if he refused then he should forfeit the money, instead “the cloaths belonging to his former wife should be delivered to him”. (It sounds as though the previous wife’s old stuff had been a bone of contention!) Sister Elizabeth was to have her “plain gold watch”; sister Sarah “a green ring set with diamonds”; to her niece Hamer (?) £40 and a repeating watch, with nephews Hamer, Barnsdale and Molton £10 each.

(Of the relatives mentioned I can only identify “nephew Barnsdale”. Mary Jefferies married William Barnsdale by a licence issued in the Bristol diocese in 1717. This couple must be his parents. Mary who was baptised in 1693 at St Nicholas, Bristol, was the daughter of Joseph & Mary Jefferies. Frances Jefferies (Mrs Ruscombe) was her younger sister baptised St Nicholas on 20 January 1700. Other sisters Ann, 1695 and Sarah, 1701, were also baptised at the same church as well as a brother, Joseph in 1696. The “former wife” mentioned in the will but not named is the only evidence I have that there was a first Mrs Ruscombe.)

On October 6, Mr Nugent, the MP for Bristol, added another £100 to the reward fund and a day later the King himself became involved offering a free pardon to any accomplice who would give evidence after the fact. Several people were “taken up” and questioned, but it was a case of “round up the usual suspects” and all were released without charge.

On October 13 there was a sensation. A letter, supposedly written by Mrs Ruscombe was found dropped near the turnpike at Devizes, allegedly by two sailors who had recently gone through the tollgate. Mr Whatley, of the Black Bear Public House formed a posse and chased after the two men who were arrested after a struggle. They were brought before Mr Justice Popham of Hungerford and questioned. Luckily for these two unfortunates, they could prove they were in Wells when the murders were committed and they were released. After all the kerfuffle the paper was examined and found “not to be in Mrs Ruscombe’s handwriting”. It was a hoax. On October 20, another suspect was presented. Rumours abounded that the landlord of a Bedminster pub had suddenly departed in a post chaise in suspicious haste. Excitement bubbled over when someone said he had told the driver of the chaise to “keep to the side lanes”. This was enough to send another crowd of zealous citizens in hot pursuit; the landlord was apprehended in Plymouth. Who or what was he running from? Creditors? A jealous husband? Leaving his family chargeable to the rates? Whichever, or none of these was revealed. In any case his flight from Bristol had taken place the day before the murder.

On October 27 at last, a more likely suspect was questioned. A neighbour came forward who alleged that she had seen Mary Champness arguing with a man in the street. The informant assumed she was witnessing a lover’s tiff, but warming to her theme, she said when the man went off she heard him swearing revenge. A former suitor of Mary’s was then arrested. He said he was not the man seen rowing with her, and in any case had not seen her since the previous February. He was released. The man in the argument, if he existed was never found.

November 3: back to the ever more bizarre list of suspects. A girl who was travelling “with a tinker and his trull” was suspected and examined; she was a pretended fortune teller and said she had information. The story she gave, not divulged, was proven to be false, and the girl was released. On November 10, new information: “a small oblong silver chased snuffbox with the gilt worn off” belonging to Mrs Ruscombe was belatedly added to the haul of cash said to be missing from the house in College Green. Pawnbrokers were alerted, but nobody offered the object for sale. After this latest setback, the papers lost interest in Mrs Ruscombe and Mary until April 27 the following year, when more farce ensued. A Mrs Wilson, “a notorious individual” had been a suspect in the murder of a tollgate man, and had also been tried at the Old Bailey with killing her illegitimate child. She had been cleared on both counts, but mud sticks, and for want of something better to do, Mrs Wilson was questioned about Mrs Ruscombe. It seems that Mrs Wilson thought she ought to say something, or else she had an eye on the reward. She gave a garbled account of a pair of salt cellars belonging to Mrs Ruscombe that she said she had seen. The newspaper, exasperated, reported “as no such things could be found and she has been detected in many other falsities, it is believed she is an impostor and the whole of her story fell to the ground.” Mrs Wilson was released.

Nobody else was questioned though rumours abounded that a baker called Peaceable Robert Matthews was guilty of the crime. It was said that Matthews had confessed the fact to the Rev Mr Seyer, who had been sworn to secrecy, but Mr Seyer broke the rule of the confessional and told Mr Catcott, the vicar of Temple; Mr Catcott told it to another gentleman and this gentleman told Mr H. and Mr H. told Mr I. and Mr I. told the World. Chinese whispers. Then, yet another cleric, Rev John Casbend entered the discussion. He had given the sacrament to the late Peaceable on his death bed and felt sure that if the man was guilty he would have confessed then. Casbend felt so strongly about the matter that he published a tract addressed to the citizens of Bristol called “A vindication of Peaceable Robert Matthews for a charge of Mrs Ruscombe’s murder, lately revised against him.” There seems to have been no more evidence against Matthews other than the rumour of the so-called confession and unfortunately Mr Casbend supplied no details other than his flat denial that the baker had been involved.

So who did kill Mrs Ruscombe and her maid? The most likely explanation is that Mary Champness herself, knowing of the stash of guineas in the upstairs room conspired with the “man in the street” to commit a burglary at the house. She could have let her accomplice in. We’ll say Mrs Ruscombe herself disturbed him in the act, and he killed her. Mary who had not expected violence, opened her mouth to scream, and in order to shut her up, he killed her too. He then made his getaway with the loot the sisters remembered a week or so after the murder. But how did a man covered in blood manage to escape in broad daylight without causing comment?

Where was James Ruscombe when the murders occurred? It does not seem Mr & Mrs Ruscombe lived together. As far as I can tell he was never questioned. Perhaps the idea of his guilt was unthinkable. He was too respectable perhaps, a son of a landed family in Somerset. Mr Ruscombe is mentioned only once during the entire proceedings when he added a skimpy £10 to the reward fund.

James Ruscombe, a sail maker, and Frances Curwen were married by licence at St Augustine’s church Bristol on 5 February 1754. It was a second marriage for both. Frances was the widow of a Bristol merchant, Christopher Curwen, who after a few ups and downs, a bankruptcy in 1741, died in 1749. Frances Jefferies and Christopher Curwen were married at St Stephen’s, also by licence on 16 September 1731. None of the marriages produced children.

After the furore James Ruscombe married a third wife, Elizabeth Hill at St Michael’s, Bristol in 1769. This marriage was also childless.

By the time he made his will he had retired and returned to his home village of Cannington in Somerset. He scattered legacies about like confetti: £200 to Mary Marshall, natural daughter of John Daubeny, late of City of Bristol, mariner; £200 each to his nephews Richard & William Ruscombe, & kinsman John Murry, son of late niece Mary Murry £200 each; Mary Murry sister of John, £300; nephew Henry Ruscombe of Durston, Somerset, & kinsman William Murry of Cannington, yeoman, £600 each; three nieces, daughters of his late brother Richard Ruscombe to wit, Honour wife of John Robins, Betty wife of William Cox, Joan, wife of John Masters, £50 each (or if they died before him, divided between their children); suits of mourning for his serving maid & boy; his executors to make an inventory of his goods; to be buried next to his father; Codicils left smaller sums of £5 each to his Goddaughters Sophia Poole, daughter of William Poole and Sarah daughter of William Murry, and cousin Henry Ruscombe.

All of which makes his last page mention of his “loving wife Elizabeth” somewhat puzzling. To her he left “the sum of £50 over and besides the furniture I settled on her at the time of our marriage to be paid two years after my decease……£40 by way of a legacy and £10 for mourning; to have the full liberty of living in and enjoying my new erected dwelling house and garden at Cannington and all the household goods and furniture for her natural life as long as she resides in Cannington.”

What was the woman supposed to live on? Did she have to go cap in hand to the residual legatees (and executors) Henry Ruscombe and William Murry?

It seems possible that the “new erected house” was Ruscombe House, “a detached house, set back from street in Cannington, dating from the late C18 or early C19. Brick, double

Roman tile roof to coped verges. Symmetrical front, L-plan with wing to rear and swept down roof. Three-windowed, 4-pane replacement sashes to first floor, 3-course string, late C19 or early C20 canted bays flanking a late porch with 4-panel part-glazed door; front flanked by raised quoins. Rear wing contains C20 windows.”

There are so many unanswered questions but one thing sticks out a mile. From the two wills it is clear that both Ruscombes were much more involved with their own extended blood families that with their spouses.

“Mr James Ruscombe of Cannington” was buried at Lyng on 7 September 1779. Mary Ruscombe, his widow, evidently did not stay at Cannington. She was buried at Chilton Polden on 1 June 1799.

—————————————————————————————————————-

N.B. The murder of the two women may have had a different outcome if a proper investigation had been possible. On 19 June 1829 Sir Robert Peel’s Metropolitan Police Act came into force replacing the previous system of parish constables and night watchmen. The Act paved the way for the establishment of countrywide Police Forces. The Bristol Police Force was established in 1836.

A version of this article appeared in B&AFHS Journal no.103, March 2001. I am grateful to Jane Bambury of the Society for pointing out that in 1764 a married woman was able to own property in her own right.

Blog Comments

Terence William Townsend

27th February 2022 at 7:21 pm

I have just discovered this in the book ‘On the Level’. by Geoff Treasure: James Ruscombe, part owner of the slave ships Africa and Valiant, is buried in the churchyard at Lyng. In 1774 the Africa made four voyages as part of the slave trade. James had one eighth investment in the boat. He also had a third stake in the voyage of the Valiant in 1777 when he was well into his seventies. Why Lyng became his final resting place is unknown.

QE! (pen name of Richie)

25th August 2022 at 11:07 am

I happened upon your blog while searching for links to the Mrs Ruscombe case. I must say that I look forward to reading your blog over the next few days and ongoing, as you add more discoveries. My primary interest is Thomas Chatterton, hence the website mentioned above. I am currently transcribing one of Richard Smith’s notebooks, which deals mostly with the Goodere murder. Richard Smith, as you know, was a famous Bristol surgeon in the 19th century, which makes him very interesting, but it is a bit of detour from what I was supposed to be working on (transcribing the copy-books of George Symes Catcott), but that’s the problem and the joy of researching historical things, it is so easy to be sidetracked. Richard Smith wrote about the Ruscombe/Sweet murder in a privately published pamphlet, and also mentions it in his notebook. I hope you don’t mind but I have added a link to your blog, specifically the page dealing with the Ruscombe/Sweet case. Thank you for a most enjoyable blog on Bristol. Richie

dp lindegaard

25th August 2022 at 7:59 pm

Thank you for your kind comments. I will put a link on the blog to your Chatterton Project. I do know how easy it is to become sidetracked – I am a world authority! I did stuff on the Goodere murder many years – about half a century – ago but I don’t know what became of it. I came across the Catcotts then too when I was researching an elusive woman called Jane Bond, who married into the Wigan family. Through Jane I came across lots of people who belonged to the Unitarians, who I christened “The Friends of Jane Bond”, middle-class, educated, and in trade, quite different from my own Kingswood coalminers. I seem to remember – and I believe it was a Catcott, in the 18th or early 19th century, having written the words “his death freed her from a life of inhuman bondage” which I read in papers at Bristol Archives. “The Friends” may be a subject for the blog (hopefully) this winter, my age and poor eyesight permitting. Thank you again for your encouragement.