Would any of this have happened if we hadn’t come to Brislington to live? Perhaps, perhaps not. I never had anything to do with Brislington before and although I knew vaguely that it was south of the river in Somerset as opposed to my own Gloucestershire territory, I would have been hard pressed to pin point it exactly on a map of Bristol. Our first house was in a long terrace, Wick Road, an ancient Salt – or White – Road built above a Pilgrim’s Way, which followed a quiet stream along a wooded valley to a once famous shrine at St Anne’s. Judging by the depth of the ravine – known to the locals as “the dip in Allison” – through which this now timid waterway flows, a few million years ago it was a raging torrent.

The house was not bad at all, but the tiny front garden opened almost straight into the traffic of what would become known as a ‘Rat Run’, worrying with three adventurous toddlers anxious to take off into the wide world the minute my back was turned. So after a year or so, we moved, barely half a mile, though a world away, to a post-war house in a road built on the site of a WW2 US Army Camp, in ‘old’ Brislington, not far from what is laughingly called ‘the village’ though the former 19th century bucolic watering hole is now dissected by the A4. Likewise most of the grand merchants’ houses are long gone as are nearly all the old cottages, the dwellings where the ag. labs, gardeners and domestics who had served these grandees lived. A notable exception is ‘Nelson’s Glory’, a few yards away in School Road, which then unbeknown to me was once the home of a family who shared my maiden name: Pillinger! (‘LET EV’RY MAN DO HIS DUTY’ is the patriotic paraphrase on a plaque set into the wall of the cottage.) The tower of the 13th Century Parish Church, dedicated to St Luke, is, like most old churches, built on a hill, and stands proud over the house tiles, ancient and modern; we still have some of our green spaces, though despite the protests, the marauding Council fancied a large housing estate to cover over our fields and sadly, in 2021, it looks as though work has started, though is presently at a standstill due to Lockdown. I remember how ecstatic we were that we could cross a road, go through a gate and along a lane to meadows where cattle grazed. Alas the farmer is long dead and the cows no more, but the fields are still there – for the moment at least – used now by dog walkers, including us, and as a pleasant short cut to the nearby trading estate.

When we first arrived, our children were 4, 3 & 2 and I was a stay-at-home Mum. How lucky I was! Each day, after a brisk trot through the house with a feather duster, come rain or come shine, we would go out to explore our new territory. Being something of a flower child and an old hitch-hiker, I had the very name for these outings: ‘The hippie trail to Afghanistan’. This had an unforeseen consequence when the USSR invaded that afflicted land a few years later “We’ve been there, haven’t we, Mum?” said the worried eldest child and I had to reassure my infantry that it was not actually within walking distance. We had our adventures: on one memorable day we hitched a ride from a passing boatman on the river Avon at Conham who loaded us all aboard and rowed us across the river to Hanham and another county. We arrived at ‘Nana’ Pillinger’s in Kingswood in the twinkling of an eye, but that’s another story.

On the day my long journey with my ancestors began, we set out as usual on a wintry day in 1972, my boy Kevin in his push chair (they were not called buggies then) and my two little girls, Caroline and Celia, trotting along beside. We were wending our merry way through the churchyard when it started to drizzle. I had not taken much notice of the names on the gravestones up to then, but this time, suddenly, one stood out and poked me in the eye. Not a ghost, but as good as.

“STOP!” it commanded sternly. “STOP AT ONCE! LOOK AT ME! I’M DOWN HERE!”

I obeyed, nearly falling over and almost pitched the baby onto the cold ground. He wailed in protest as I investigated the message.

The inscription on the flat stone in front of me came through loud and clear:

Sacred to the Memory of James Pillinger

who died July 25th 1824

Aged 68 years

And Hannah, wife of the above who

died April 17th 1839

Aged 79 years.

Death may our souls divide

From these abodes of day

But love shall keep us near his side

Through all the gloomy way.

I had always been a history buff but surely, history was all about kings and queens, great battles and politics, wasn’t it? Not ordinary people. Not like us. When I told my brother, Colin Pillinger, (later of Beagle 2 fame), he astonished me with his nonchalant reply.

“Why don’t you ask the vicar if you can look at his records?” he said.

Incredible as this seems now, I had no idea there were parish records, let alone that they contained details of us, the hoi polloi, as well as the nobs, and that they went back centuries. So it was that a few nights later Colin and I were installed behind a vast mahogany table at the vicarage, poring over the church archives. Mrs. Austin Allen, the vicar’s wife, ramped up the suspense, producing volumes one by one, some registers bound in white leather. They contained the baptisms, marriages and burials of Brislington’s erstwhile parishioners hand-written by previous clerics, variously faded, sometimes blotched and occasionally hard to decipher. And……..the registers rained Pillingers which we eagerly harvested like so many fallen apples. In the blink of an eye we would meet a baby at his christening, be a guest at his wedding twenty years later, rejoice at the births of his children, (sadly, often as not buried in infancy), then finally there would be his own burial, if he was lucky, a few further decades on, a chilling reminder of the fleeting nature of all our lives. As well as the sparse details contained in the registers, our parish is fortunate that in 1822, an eager young curate, called Charles Ranken decided to round up backsliders who were seldom seen in church. He knocked on doors, interrogated the occupants and wrote them down in his notebook. Were there Pillingers among them? You betcha.

‘Aged between 60 and 70’, the Reverend wrote of the various individuals; ‘has two children living’; ‘reads and can write a little’; ‘has a Bible’; ‘seldom goes to church’; ‘takes in washing’; ‘is in the Friendly Society’; ‘has a nurse child’ ; ‘works for himself at Nelson’s Glory’.

Pure gold. We scribbled and scribbled. It was cold, our feet went to sleep, our teeth chattered but still we wrote…..and copied and wrote.

Then we were back to 1731, and the flow suddenly stopped with the baptism of Sarah, the daughter of Jeremiah and Betty Pillinger. There were no more Pillingers before that. Mrs. Allen said “They must have come from somewhere else,” and began packing up the books and replacing them carefully in the Parish Chest. Buzzing excited thank yous, we dropped a donation in the offertory box, packed up our notes and left. We had done our family history in an evening. All we had to do now was put it together into a Family Tree.

About a week later, satisfied with our efforts, (mostly Colin’s suppositions) we took the finished article to show our Dad, Alfred Pillinger, but commonly called Jack:

“Now Dad,” we said, puffed up with pride, “Show us which one of these is your grandfather………”

He put on his specs, looked hard and looked again. A hush descended. Then breaking the silence he said……….

…………………. “None of them, y’dummocks. We all come from Kingswood!”

Not only that; our Pillingers were Chapel people, he said. Methodists, Wesleyans, three times on a Sunday, as well as midweek, ‘Bible Class’ and ‘Band of Hope’. As a boy he always ran down to see his grandfather Burchill, his mother’s father, “On a Sunday. I ‘ud read to ‘un outta the Bible. ‘E couldn’t read nor write.”

The Kingswood Pillingers, our ancestors, were harder to pin down than the Brislington family. They dodged about so. Perhaps they were searching for ‘the truth’, so over time chopped and changed, between Church and Chapel, as well as between one Chapel denomination and another: there were plenty of such places in Kingswood to choose from.

“Some on ‘em gave better teas than others,” Dad suggested, ever pragmatic.

Kingswood had, after all, been in the forefront of the non-conformist revolution, ‘the Great Stir’ of 1739-40 when John Wesley, George Whitfield, John Cennick and others had preached the Gospel to the ‘ignorant colliers’ in the open fields and promised them a better life in the world to come.

The Pillingers led us (me in particular) quite a dance, not only in Kingswood. I came to know the local geography like the back of my hand, and as well as that, they took me to places I had never heard of before. In those days, the early 1970s, nearly all Church of England registers were in the care of the incumbent vicar rather than as now, in County Record Offices.[1] The custodians came in extremes. Some were hospitable and kindly, others were ‘tricky vicars’ among whom was one who kept me on a knife edge for years, with excuse after excuse, too busy, weddings, funerals, Easter, Christmas, visits from the Bishop, the Archbishop……. I never even got as far as the vestry there. He was finally forced (by law, in 1978) to hand his registers over to the Wiltshire Record Office for safe keeping, where at last I was able to see them. An archivist, unbidden, told me,

“We had to literally prise them off him. He sat in the corridor, fuming, and holding them tightly to his chest shouting ‘these belong to me! You’ve no right!’….…”

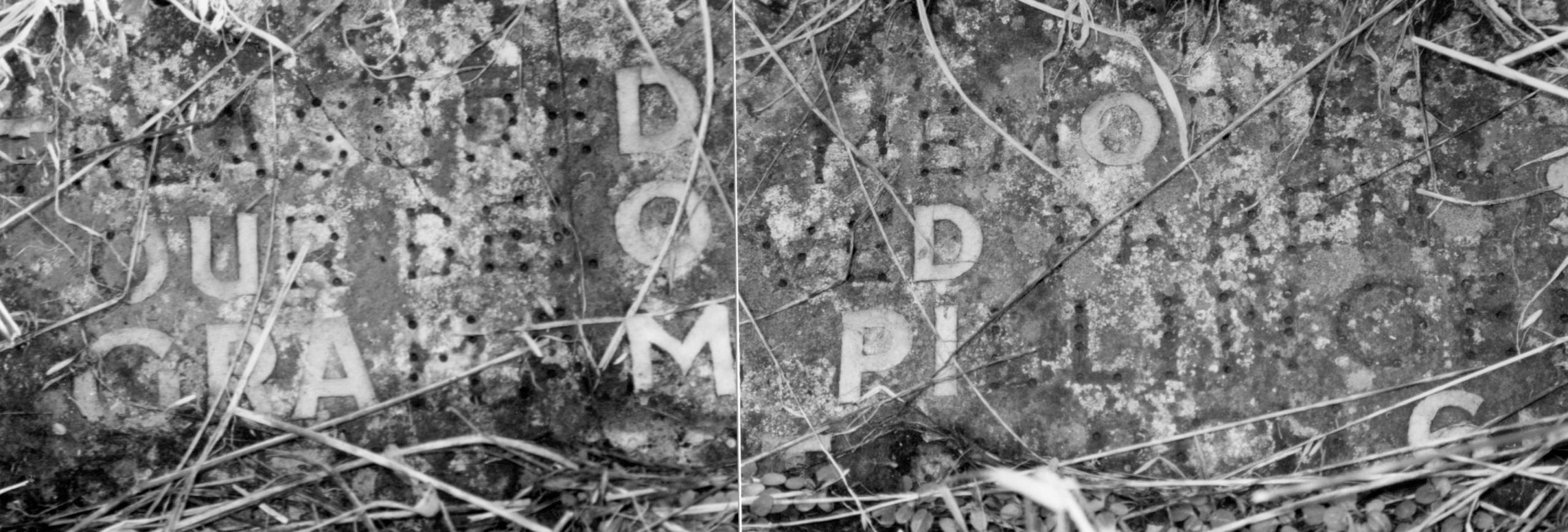

Many of our recent kin lie buried in the Wesleyan churchyard in Kingswood. I searched the grave records then at Bamford’s, the ironmongers, for ‘safe keeping’, under a dreary yellow light bulb in an upstairs storeroom among boxes of screws, nails and tools of every sort. I took down all the family members. Now I wish I had listed everybody else too, for the records have now, inevitably, vanished. A few years ago I heard from a couple of helpful ladies who said they had them. I rushed to visit them. Then it turned out they didn’t have them at all. What they had was a monograph of the names on the chapel tombstones, “Monumental Inscriptions”, a different thing altogether: only a few Kingswood Pillingers were posh/rich enough to have gravestones as opposed to the yards of them who had unmarked graves. Despite my disappointment, thank goodness I didn’t say “Thanks, but no thanks,” to the ladies, for this typescript list is now itself worth its weight in gold (my interests have expanded), the chapel itself is now roofless and the “unsafe” graveyard is an inaccessible island, overgrown and boarded up, hazardous, out of bounds to everybody. (‘elf ‘n safety’ of course). In the days when it was still possible to wander about there, it was even then full of hidden perils; I spotted the letters Gra—-m Pi—– on a fallen stone and on further investigation fell through the bramble undergrowth and full length into the grave itself.

(“Trying to cut-out the middle man?” enquired Dad’s sardonic ghost.)

Clambering out, I ripped my trousers and despite the blood dripping down my legs from my scraged knees, managed to take a picture:

Thus the years passed by. A tap had been turned on. Dad’s ancestors; Mum’s ancestors; the ancestors of my Danish/Irish in-laws; my next-door-neighbour’s ancestors; later our grandchildren’s ancestors; anybody’s ancestors; it became a cottage industry: booklets ‘Kingswood Annals’; ‘Brislington Bulletins’; ‘Black Bristolians’; ‘Killed in a Coalpit’, and more. Neither were the long line of Brislington Pillingers allowed to rest in peace. I researched them as well; along with Pillingers from everywhere else. Of course I did.

When I started this quest, not only were the parish registers in individual churches, the civil records of births, marriages and deaths (from 1837 onwards) were at St Catherine’s House in London, in huge tomes that had to be hefted from high shelves, a separate list for each quarter, with rudimentary indexes which gave name, number and district only with no certainty that the certificate containing the vital information for which you paid your money was the correct one. Censuses (at the time 1841-61 were all that was available) gave more information about who was who, with ages and occupations, and were (oh joy!) at Bristol Library but unindexed, and had to be accessed on spools of microfilm, with much cranking of the handles of antiquated readers, (groan!)

I was at the first meeting of the Bristol & Avon Family History Society in 1975. In 1979, an ITN newsreader, Gordon Honeycombe, (who died in 2015) hosted an inspirational TV series called ‘Family History’ based on his own research. We were years ahead of our time. Now Family History is everywhere. Everybody is at it. There have been umpteen series of ‘Who do you think you are?’ on BBC and plenty of other spin-offs. With the Internet,

“everyfink’s on there, in’it?”

is the oft repeated mantra. Now the craze is all for DNA.

Time passes. We made our own family history, with good years and difficult years. What doesn’t kill you makes you strong. I was emerging from one of our periodic sloughs of despond. We were stony broke and I was in a dead-end job and more than usually irritable having just given up smoking. Caroline, our eldest, home that weekend from University, said

“Why don’t you do a Mature Student’s degree?”

“But I haven’t got any A-Levels,” was my doleful reply.

Caroline, unlike me, is a glass-half-full person.

“No, but show them your research,” she said, with super confidence.

1943: Me aged 6, with my baby brother Colin, aged 0

“Luck”, Seneca said, “is when preparation meets opportunity”. I got into Bristol Polytechnic which has since gone up in the world as ‘The University of the West of England’ without an A-Level to my name – a Beak riffled through my pile of booklets and nodded me through. He handed me forms inviting me to apply for a grant. A grant! I couldn’t believe it. Three years later I graduated with a BA. Then I got the best job I ever had in my life, working for a Member of Parliament. I stayed for nearly twenty years until I was seventy three.

And all through a walk in the churchyard. Kevin, the boy in the buggy was married at St Luke’s. The bride and groom had their photo taken by the famous Pillinger grave. Family History. I’m still at it. Each time I finish a project I say “I won’t do another one.” And my long suffering old man, who agrees with Henry Ford that, “History is bunk”, says “You will. You will.” And of course, I will. Here I go again!

[1] Many of course are now on-line: very convenient, but not half as much fun. Then, you might travel fifty miles and come home highly satisfied at finding one previously unknown entry. Don’t knock it though. It’s now so much easier.

This article was first published in the Bristol & Avon FHS Journal, June 2021. Issue No. 184

Blog Comments

Caroli

8th June 2021 at 2:18 pm

A wonderful achievement well done.

Caroline Boothroyd