My previous subject (Mary Kennedy, as far as we know) wrote only one line about her voyage to the other side of the World and back. By contrast Anna Maria Falconbridge is her direct opposite. Anna Maria was interested in everything. Her “Narrative of Two Voyages to the River Sierra Leone during the years 1791-1792-1793” is mainly composed of letters written to a supposed friend in Bristol.

She is not a fashionable subject, probably because she exhibits something of an ambivalent attitude towards slavery. This cannot be said of her husband Alexander Falconbridge, an idealist, who was one of Thomas Clarkson’s most enthusiastic supporters. Falconbridge having had first-hand experience (four voyages) as a ship’s doctor aboard slaving vessels had become so disgusted by the slave trade that he offered his services to Clarkson, the anti-slavery campaigner, as a guide round the sleazy haunts of Bristol, enabling him to collect damning evidence against the infamous trade.

Anna Maria Horwood was Alexander’s junior by nine years. She was the well-educated daughter of a middle class family “in trade” whose business was situated in All Saints Lane, Bristol.

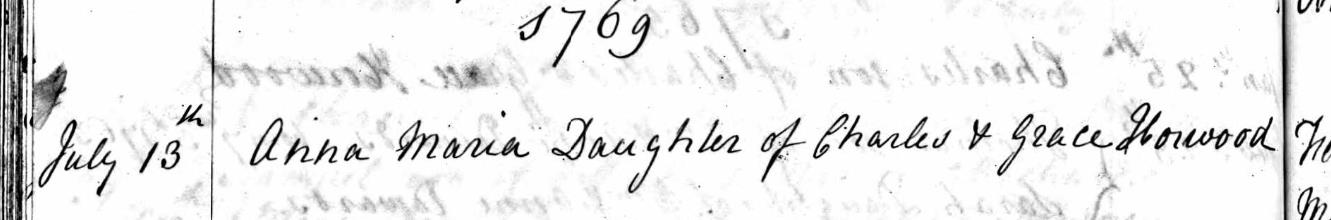

Her parents were Charles Horwood, junior, (as he signed himself) a watch and clockmaker and his wife Grace, formerly Roberts. She was the youngest child of six, five girls and one boy, the others being Mary Anne, born in 1760, Grace, 1762, (who died aged nine), Anne, 1763, Charles, 1765 and Christian Jane, 1766. Anna Maria would have had little memory of her mother who died in 1772 when she was just three years old. After six years of widowhood her father, by then described as a silversmith, married a second wife, Martha Cox. Several more children were born including a set of twins.

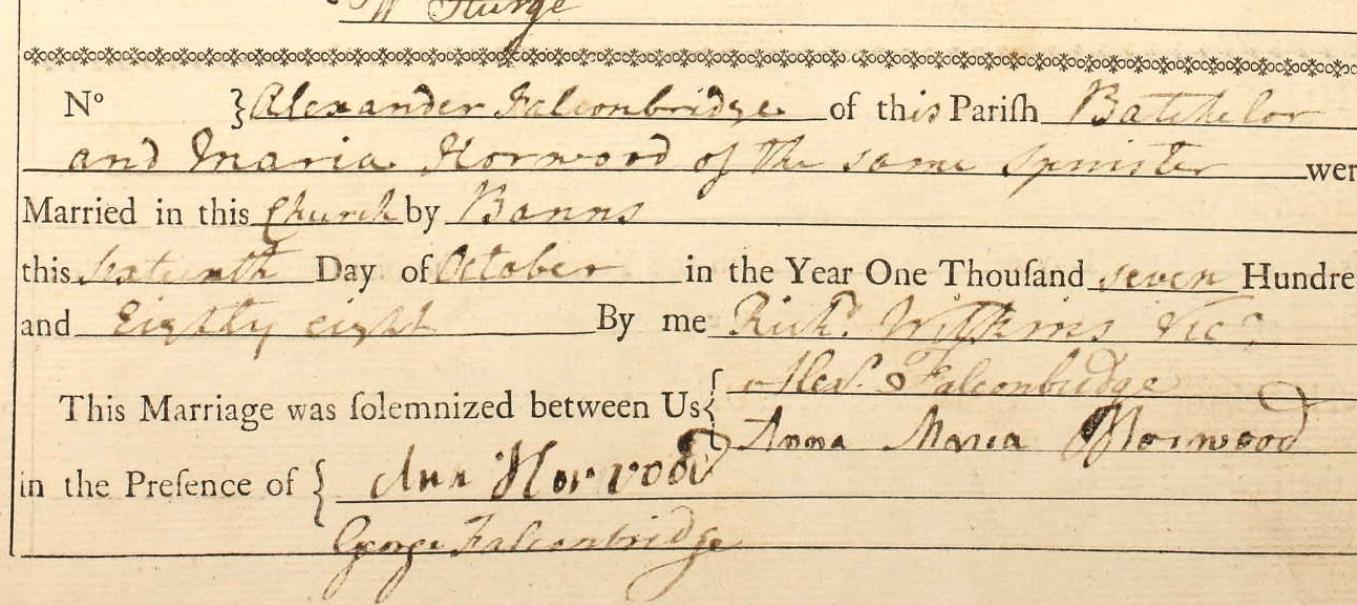

Anna Maria Horwood aged nineteen, and Alexander Falconbridge, (a man whose brilliant name conjures up a romantic hero worthy of Scott or Stephenson), were married in 1788, a year after her father’s death. Anna Maria asserts that the wedding took place against the wishes of her family and friends, though one member of the family must have stood with her, Anne, her sister, who signed the marriage register as a witness along with the bridegroom’s brother George. The wedding took place out of sight of Bristol at the Somerset village of Easton-in-Gordano, though unlike her father’s two marriages, there was no licence. Banns would have been called on the regulation three Sundays prior to the ceremony, allowing plenty of time for any outraged parties to have made their objections known. It is suggested that the Horwoods had slaving connections and thus would have disapproved of Anna Maria’s choice of partner. In a small anomaly, the bride is recorded as “Maria Horwood”, though she signed the register in full as “Anna Maria”. Both parties were stated to be “of this parish”, that is, resident at Easton-in-Gordano, which is adjacent, even part of the little Bristol Channel port village of Pill.

Alexander Falconbridge had perhaps actually lived up to the heroic promise of his name. Clarkson, who was grateful for his support, on occasions as a bodyguard, held him in high regard, describing him as “athletic” and “resolute looking”. He was born about 1760 and in 1779 had become a pupil doctor at Bristol Infirmary. As he had neither sufficient funds nor a wealthy patron to set himself up in private practice he was drawn to life aboard a slave ship, which would have been “a potentially lucrative employment since surgeons, as well as their salary received a shilling a head for every slave landed.”[1] At first he supported the slave trade, saying,

“I entertained a belief, as many others have done, that kings and principal men bred Negroes for sale as we do cattle.” [2]

The year before the wedding Falconbridge was encouraged to publish his story and duly produced “An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa”. Six thousand copies were sold. With some of the proceeds of the pamphlet Alexander set up in general practice at Lodway in Pill. Whilst not exactly at the hub of municipal affairs it offered the couple a definite improvement in their circumstances. They hardly had time to settle into country life before everything changed. Clarkson asked Falconbridge whether he would testify before a House of Commons Committee. When he agreed, Clarkson’s response was emotional: “Never were words more welcome to my ears. The joy I felt rendered me quite useless…” Over four days in 1790 Falconbridge was questioned about his experiences of the slave trade by often hostile MPs. If Bristol had not heard the name of Falconbridge before this time, then now he was on everyone’s lips, hero or villain depending on which side you supported. Then Clarkson offered Falconbridge a job.

A few years previously a scheme had been devised for the re-settlement of London’s “Black Poor” in Africa. Many of these were loyalists, escaped slaves, who had been promised freedom and a grant of land if they fought for the Crown in the War with America. Some of these people made their way to England and disappointment. The grant of land was mythical, but a committee was formed in an attempt to right the wrong. A scheme was mooted to re-settle the loyalists in Africa. In 1787 an expedition was fitted out, destination Sierra Leone, made up of about 300 of the black loyalists, 60 working-class white women as their wives (propriety was observed – they were married beforehand) along with clergy, officials and craftsmen to assist in building a colony. The colony, not surprisingly struggled, and by 1790 it had failed. Disease wiped out many of the colonists, and the rest, caught in the cross fire of disputes between a local tribe and slave traders, fled when their settlement was burnt down. Alexander Falconbridge’s task would be to act as agent for the newly formed St George’s Bay Company, to round up those remaining of the displaced community and get the settlement up and running again. All very worthy and idealistic; the young couple’s sense of adventure prevailed, overcoming prudence. Alexander had no administrative or commercial experience, the lack of which, with hindsight, Anna Maria would comment on.

January 1791 found them in Portsmouth, aboard the “Duke of Buccleugh” under Captain Maclean, along with Alexander’s brother William. They carried with them gifts for the local chiefs to persuade them to allow the wilderness of the proposed Granville Town to be re-settled.

Anna Maria did not go ashore in Portsmouth:

“I was once there and few people desire to see it a second time,” is her pithy dismissal of the place.

She noted the presence of a fleet in the harbour, making ready to sail for Australia with the miserable convicts shuffling aboard the ships in their chains:

“the sight of those unfortunate beings and what they must endure have worked more on my feelings than any accounts I ever read or heard of wretchedness before.” [3]

The reasoning for the re-settlement of petty criminals as Empire Builders sounds very similar to their own mission, though Anna Maria did not make the connection.

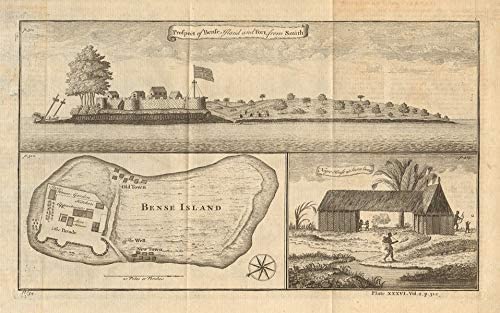

Their voyage to Sierra Leone, with a following wind took a scant eighteen days. The “Duke of Buccleugh” belonged to the London firm of John & Alexander Anderson & Co, of Philpot Lane, Fleet Street, who also owned “the Factory” on Bance Island[4] in the Sierra Leone River; where slaves were kept caged until they could be forced on to the ships. It was one of the most lucrative enterprises in Africa. The Anderson brothers were firmly against any restrictions in the running of the slave trade. (Towards the end of her stay in Sierra Leone, Anna Maria would report the departure of the “Duke of Buccleugh” for Jamaica with 300 hundred slaves.)

By February 10th, Anna Maria was thrilled by the scenery of Sierra Leone, the mountains rising gradually out of the sea to a stupendous height, but she was less happy with their accommodation, on a small boat, a cutter called the “Lapwing”, which the Company procured and had sent out separately.

“A tub of a vessel…. a hog-trough…. imprisoned in a floating cage…..disgusting……. the stench continually assailing your nose…”

…..are some of her angry descriptions of her lodgings. She would have preferred to stay at the Fort on Bance Island, despite the proximity of the Factory. Finally a reluctant Falconbridge allowed her to go ashore so that the cabin (from which the ship’s captain had been displaced in Anna Maria’s favour) could be scrubbed out with vinegar.

Once on dry land, she encountered several of the gentlemen residents from which it is obvious she enjoyed male company. On another occasion she was charmed by a Frenchman, Monsieur Rennieu, who invited her to visit his “Factory at a small island called Gambia”.

The first time Alexander and his wife were invited to dine with the locals they discovered that almost every one of the company had a financial interest in the trade. The atmosphere was edgy to say the least. Falconbridge bravely stood his corner, “zealous for the cause……. [he] strenuously opposed every argument they advanced in favour.” Zachary Macaulay, who would become the second governor of Sierra Leone grumbled that he gave the slave traders every impression he was out to ruin them. Anna Maria who retired early, leaving the men to it, noted that Falconbridge displayed a fondness for “the glass which went swiftly round.”

Relations were more cordial with King Naimbanna who ruled over the neighbouring Temne tribe who they met for the first of many palavers.[5] The King, who received them with good will, was flamboyantly attired….

“….in a purple embroidered coat, white satin waistcoat and breeches, thread stockings and his left side emblazoned with a flaming star; his legs to be sure were harliquined by a number of holes in the stockings through which his black skin appeared.”

During a brief interval the King absented himself and then re-appeared dressed in a black velvet suit, though wearing the same holey hose.

Through the long negotiations Anna Maria amused herself by imagining she had offered to mend his stockings, but feared…

“…lest my needle should blunder into His Majesty’s leg, for drawing the blood of an African King, I am told, [even] by accident is punishable by death.”

“He is above common height but his features resemble a European more than any black I have seen; his teeth are mostly decayed, and his hair, or rather wool, bespeaks old age, which I judge to be about eighty. He was seldom without a smile, but I think his smiles were suspicious.”

“The Queen stood behind the King, eating an onion I gave her, a bite of which she now and then indulged her Royal Consort with. Silver forks were placed on the King’s plate and mine, but nowhere else.”

On another occasion the King told Anna Maria that she was the first woman that ever ate at the same table with him. Though the women did not sit down to eat with the men, Anna Maria recorded her astonishment at their drinking. “They would down half pints of rum as I would water.”

“The Queen is of middle stature, plump and jolly; her temperament seems placid and accommodating. Her teeth are bad but I dare say she has been a good looking woman in her youthful days. I suppose her to be about forty five or forty six, at which age women are considered old here. She was dressed in a dignified manner, having several yards of striped taffety wrapped round her waist as a petticoat; another piece of the same carelessly thrown over her shoulders in the form of a scarf; her head decorated with two silk handkerchiefs, her ears with rich gold earrings and her neck with gaudy necklaces, but she had neither shoes nor stockings on.”

During the King’s speech, she would regularly call out “Ya Hoo! Ya Hoo!” obviously the equivalent of “Hear! Hear!”

The higher classes spoke in broken English from intercourse with slavers and were keen on education: “Read book. Learn to be a rogue as well as white man.”

Clara, the King’s daughter was the wife of Elliott Griffith, a freed slave, one of the Nova Scotian Loyalists who came out from London with the first contingent of colonists. A poor boy made good, he was not only the King’s son-in-law but sat at his right hand for palavers, acting as scribe and interpreter.

Anna Maria had Clara with her for four days but was not happy with the arrangement. She found “this Ethiopian Princess trying…….impetuous, litigious and implacable.” She tried to dress Clara in European clothes, which….

“…..she tears off her back immediately I put them on.”

Originally Anna Maria was disconcerted to see that the local women went bare-breasted, but learned to take it in her stride. She observed that from shortly after giving birth, women carried their infants wherever they went until they could walk. The child’s legs would be buckled round the mother’s waist, hence most had bandy legs, including the king.

“The women are not nigh as well-shaped as the men; being employed in all hard labour makes them robust and clumsy. They are prolific and keep their breasts suspended which after bearing a child or two stretches out to enormous lengths, disgusting to most Europeans, but considered beautiful and ornamental here. They till the ground and do all the laborious work but are kept at a great distance from the men.”

Anna Maria was curious though equally uncritical of polygamy. The Queen was the senior of Naimbanna’s wives, but Anna Maria met several others, including his “Pegininee woman” who “is the most beautiful young girl of about fourteen.” Naimbanna would interrupt negotiations during the palaver and retire to “the Pegininee woman’s house”. Of a great or admired man, it would be said “Oh he be fine man, rich too much, he got too much woman!”

She visited the salt flats, a low muddy place, where the “profit is considerable” of huge importance to the native economy. A man would barter his wife for it. Old women -“refuse” slaves – too decrepit to interest the slavers – did all the work. She was enchanted by the King’s garden…..

“……furnished with African plants, pines, [sic], melons, pumpkins, cucumbers.”

The King cut two beautiful pineapples and presented them to Anna Maria. The palm was another vital ingredient to native life, for oil, food, even for cosmetic use: “male and female alike anoint themselves with it.” She found…

“….palm wine….. not unpleasant when first made. It has a sweetish taste and the look of whey but foments in a few days and grows sour. I think if distilled it would make decent spirit.”

On one occasion, out with Alexander, hearing “dreadful shouts”, they came upon four slave catchers in the act of putting the irons on a victim. Falconbridge did not think it wise to rescue the captive by force but remonstrated with them to no effect. They said somebody belonging to the prisoner’s village had injured them and they were taking revenge.

“They then carried him away, deprived of his liberty by the barbarous customs of his country for the imaginary offences of another.” Strangely she does not reflect that those Englishmen above the four men in the chain of command were equally barbarous. On another occasion, when she was on Bance Island, the room in the Fort where she was staying looked directly into the yard of the Factory. She saw “Two or three hundred wretched victims chained and parcelled out in circles, just satisfying the cravings of nature from a trough of rice placed in the centre of each circle.”

Negotiations with Naimbanna and the other King, Jemmy, who held sway on the other side of the river, plus other interested parties, Pa Boson, Pa Duffee,[6] Queen Yamacubba, Signor Domingo and the rest were frequent and could drag on for five or six successive days. The committee obviously underestimated the amount of work the resettlement would entail and Falconbridge was without assistance. Soon after their arrival he had fallen out with his brother, “a trifling dispute” and William had gone off in a huff. He went to work for the Andersons, sixty miles further down river where he was taken ill with a fever. He returned to Bance Island to convalesce but did not recover.

After prolonged arguments at the palaver, Falconbridge would return to the “Lapwing”, tired and irritable. Anna Maria recorded his verdict

“the wretches were only bamboozling him……they would do nothing but drink the liquor while he had a drop to carry for he was no forwarder than the day before.”

Anna Maria, when not involved in the meetings, wandered about at will, observing everything from the flora and fauna to the locals’ religious beliefs. Time is calculated by “plantations” in place of years. She had made pets of three monkeys, “one a handsome Capuchin”. She learned a few phrases: “Currea Ya?” meaning “How do you do?” and a “Congee” a farewell wave. On Gambia where she was entertained by M. Rennieu, the village houses were clean, but sparsely furnished: a block or so of wood serving as chairs, a few wooden trenchers and bowls, an iron cooking pot. They ate mainly rice, greens which she likened to spinach, and ‘pepper pot’ a highly seasoned soup which she thoroughly enjoyed.

A great day dawned when the negotiations bore fruit and fifty or so of the original settlers were re-installed in their “Town”. Falconbridge made a speech to the assembly, (“harangued them with pathetic language” according to his wife) about industry and good behaviour. He named the place Granville Town after their benefactor Granville Sharp esquire, “whose benevolence has provided their current relief.” The settlers had been issued with clothes and tools but Anna Maria dismissed some of the other supplies sent by the Company:

“chiefly blacksmiths’ and plantation tools [but] with a prodigious number of children’s trifling halfpenny knives and a few dozen scissors of the same description.” On a subsequent occasion the shipment consisted entirely of “garden watering pots” sent to a country where it rained half the year.

She was equally dry about the weaponry:

“Falconbridge has been instructed to build a fort. They have sent five cannon but no cartridges consequently the guns are useless. In any case F. does not think it would be prudent to trust them with the present settlers from a belief they might apply them improperly.”

Nor does she spare the settlers themselves: they had been asked to produce samples of country crafts, but they refused to work for less than a half a guinea a day.[7] Falconbridge is forced to pay them: “the greatest instance of ingratitude I ever met with,” Anna Maria said crossly.

A militia was raised with guards posted nightly but according to Anna Maria “we have more to fear from our people, who are extremely turbulent, than outsiders.”

Then she had a shock.

“God grant that I shall never again witness such misery as I was forced to be a spectator of here. Among the outcasts were several of our country women, [so raddled] with disease and so disguised with filth and dirt that I should never have supposed they were born white. Add to this, almost naked from head to foot, but they seemed insensible to shame or the wretchedness of their situation. I begged they would get washed and gave them what clothes I could conveniently spare. F. had a hut appropriated as a hospital where they were kept separate from the other settlers and by his attention and care they recovered in a few weeks.” Alexander, the doctor, so long a fish out of water, must have been in his element.

“I supposed they had been transported as convicts but conversation with one of them partly undeceived me. She said the women were mostly of that class of persons who walk the streets of London and support themselves by prostitution. That men were employed to collect them and conduct them to Wapping where they were plied with liquor then inveigled on to ships where they were married to black men whom they had never seen before……that the morning after she could not remember a syllable of what had happened overnight and had to ask which one was her husband……..”

Falconbridge decided to return to England to report to the Committee in person and on the 16 June 1792 they went to take leave of the Royal Family. They had already agreed to take King Naimbanna’s son John Frederick with them. The King had already sent one son, Bartholomew, to France to be educated. He seemed unconcerned to be parting with the boy but the Queen cried and was much affected. The Prince wore…..

“……an old blue cloak bound with broad gold lace with a black velvet coat and white satin breeches. A couple of shirts and two or three pair of trowsers form a compleat inventory of his cloaths. The old man gave John all the cash he had, eight Spanish dollars about thirty five shillings.”

They were presented with three goats and 4 dozen fowls from the King and other well-wishers to take on the voyage, to which they added flour, half a barrel of pork and a barrel of beef. Before they had been at sea a week, all the livestock was washed overboard. Almost everybody on board was ill with fevers including Anna Maria, and the ship’s carpenter died. As opposed to the speed of the outward journey the return took almost three months.

In Falmouth, Falconbridge went to meet Thomas Clarkson, “at whose instimulation [sic] the abolition of the Slave Trade originated and at whose instance Falconbridge quitted his comfortable situation at Lodway to enlist in the present, though I fear chimerical, cause of freedom and humanity……” (Anna Maria here regrets their English village life and, clearly fed up, thinks the whole quest is an illusion.)

As soon as they arrived in London, Mr Henry Thornton, the Chairman, expressed the condolences of the Committee for their nightmare journey home and congratulated them on their deliverance. He invited Falconbridge and the Prince to dine, telling the latter to “consider my house your home.” Anna Maria is sardonic about “the servile courtesy” that the gentlemen paid the young man, “merely his being the son of a nominal King.”

In this sketch, the young Prince is dressed a la mode. Is he denouncing the ruffian for beating the horse?

She described the young Prince, “His person is rather ordinary inclining to groseness, his skin nearly jet black, eyes keenly intelligent, nose flat, teeth unconnected and filed sharp after the custom of his country, his legs a little bandy and his deportment easy, manly and confidant. In his disposition he is surly but cunning enough to smother where he thinks his interest is concerned. He is pettish and implacable but grateful and attached to those he considers his friends. Nature has been bountiful in giving him sound intellects, very capable of improvement and he possesses a great thirst for knowledge.

“I amused myself teaching him the alphabet which he quickly learned and before we parted he could read common print surprisingly well. He is not wanting in discernment and has discovered the weak side of his patrons which he strives to turn to good account. I dare say he will in time advantage himself considerably by it.”

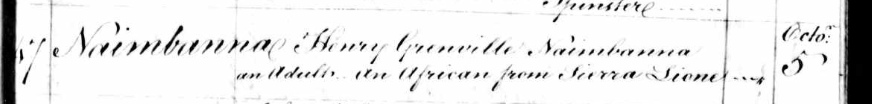

The boy continued to be feted by the Company and converted to Christianity. He was baptised at Holy Trinity, Clapham, on 5 October 1792, as “Henry Grenville Naimbanna, an adult, an African Prince from Sierra Leone”.

His baptismal names are in honour of his patrons and hosts: Henry Thornton, one of the foremost of the abolitionists, and Granville Sharp, the persistent anti-slavery campaigner.[8]

On the surface matters appeared to be going well. Falconbridge had every reason to believe that the Directors (now called the Sierra Leone Company) were pleased with his efforts. He might have had misgivings when told the startling news that Lieut. John Clarkson, RN, Thomas’s brother, would be recruiting “several hundred” more settlers from amongst black loyalists in Canada.

Anna Maria let rip: “surely a premature and ill-digested scheme to think of sending such a number all at once to a rude barbarous and unhealthy country before they were certain of possessing an acre of land and I very much fear it will end in disappointment if not disgrace to the authors……”

Only “several hundred” had been expected but Lieut. Clarkson became overwhelmed by demand. By the time 1,200 had signed up he was forced to close the list. He was obliged to charter fifteen ships to transport the eager potential settlers from Nova Scotia to Sierra Leone.

Anna Maria had doubts about returning to Africa, but her misgivings were overturned by the “honourable and handsome Directors” who raised her husband’s salary to “near three times what it was” adding “generous” sums for their out of pocket expenses (loss of clothes etc), for the purchase of personal stores plus “a very handsome supply” of comestibles for use on the voyage. Anna Maria proved susceptible to flattery. To her personally they gave another £50 to buy presents for Naimbanna and his Queen, “desiring that I shall present them myself by way of enhancing my consequence.”

The Falconbridges departed for Sierra Leone on the 19 December 1792 and arrived on 16th February the next year having stopped en route in the Canaries for “a few pipes of wine”, (each pipe contained enough for 720 bottles!) Alexander’s drinking problem was not overly specified at this time, but reading between the lines, quite obviously he did not intend to run short. They were met on arrival by Captain Wilson of the “Harpy”, a company vessel, who told them he had carried a number of passengers, Colonial officers, soldiers and independent settlers. These people entertained a false idea of their authority and constantly “snarled” at each other. Worse was to come when the Falconbridges discovered the Directors had changed the rules. The Colony was now to be managed by a Council of eight. Falconbridge would retain a seat on the board but his authority was seriously undermined. When four of the Council members came to “make their bows to your humble servant as the wife of their superior” they were dressed in comic opera uniforms, as supplied by the Directors. At a grand Council a day or two later, Falconbridge, who had expected to be made Governor was given new instructions directly counter to those he had received in London. He was informed that John Clarkson was to be “Superintendent” otherwise Governor.

The Nova Scotians meanwhile had been arriving in dribs and drabs, their flotilla having become separated from each other. A fortnight later Clarkson arrived with “the blacks from America”, the remainder. About seventy of them had perished from fever during the voyage. Clarkson himself had been ill of the distemper, but had recovered, fortunately, Anna Maria felt, as he was the only one who would have any authority over the new arrivals. Clarkson took up the reins. Anna Maria took to him at once: “an able man, void of pomp and ostentation” and so gentle she could not imagine he had ever been a Naval Officer. Unluckily he could not make a decision without the approval of the Council. There were few days without rows which not unusually came to blows….

“…….over-run with confusion, jealousy and discordant sentiments” said Anna Maria. “Members of the Council were ordering goods from the ships daily, which were not wanted and had to be destroyed, merely for the purpose of shewing their authority”……….which made them…….

“…. the laughing stock of the neighbouring Factories and such masters of the slave ships as have witnessed their conduct who must be highly gratified with the anarchy and chagrin that prevails through the Colony. The Blacks are displeased that they have not got their promised lands and so little do they relish the obnoxious arrogance of their rulers that I really believe were it not for Mr Clarkson they would drive some of them into the sea.”

There was a great deal of work to be done, a priority being the erection of temporary huts (the settlers were living under awnings made from sails out of old ships) until the land promised to them could be surveyed. Anna Maria was characteristically waspish:

“the surveyor being a Counsellor is of too much consequence to attend to the servile duty of surveying……”

The next letter is dated 1 July 1792, but instead of an improvement in the Colony’s circumstances, matters were getting worse.

“we seem daily advancing towards destruction ……..out of the 1,200 or so people living here, about seven hundred or upwards are suffering under the affliction of burning fevers. Two hundred are scarce able to crawl about, to nurse the sick or attend to domestic or Colonial concerns. Five, six, seven are dying daily and buried with as little ceremony as dogs and cats……..”

and also they were…..

“…….badly off for fresh provisions and have but a half allowance of indifferent salt provision and bad worm-eaten bread.”

With “our people” dying for want of nourishment Falconbridge proposed taking a trip

“in the Sierra Leone packet in a quest for cattle and otherwise prosecute his duties as a Commercial Agent. She is the only vessel fit for the business.” Such a trip would have had a threefold advantage

“relieve the Colony, barter away goods that are spoiling, and please the Directors by an early remittance of African production. In place of this she has been used as a pleasure boat to give a week’s airing at sea to Gentlemen in perfect health. Mr F. has had no opportunity [other than] this to do anything in the commercial way……he is placed altogether under the control of the Superintendent and Council who throw cold water on every proposal he makes. His time is at present employed in attending the sick.”

At the end of July, Anna Maria, who generally enjoyed good health was herself ill,

“confined three weeks with a violent fever, stone blind for four days, and expecting each day to be my last. I am yet a poor object and being under the necessity of having my head shaved tends to increase my ghastly figure.”

But soon a corner was turned even to the extent that “a large house of one hundred feet in length” arrived by the last ship, to serve as a hospital. (There being little new under the sun, the house must have been pre-fabricated!) Anna Maria believed it would be more suitable as a store house, as she thinks “our Blacks” would not submit to hospital treatment.

Several of the settlers proved to be good shots and went out after game, but the booty was “coarse and unpleasant”, the deer, “dry” and the pig meat “with hide an inch thick.” When one of the hunters was accidentally shot by another who heard a rustle in the bushes, Falconbridge’s surgical skills were again put to good use. He operated on the man, and “extracted several of the shot and thinks he may recover.”

During all this time Anna Maria recorded various comings and goings of company employees, botanists, mineralists, clerics, who included an American, Isaac Du Bois, though she does not mention him by name, who managed land known as “Clarkson’s Plantation” which was intended for cotton.

Also….. at long last ……“Mr Falconbridge has obtained permission from Mr Clarkson to commence a commercial career and had selected goods for the purpose but was checked by illness and now is dangerously ill. If he recovers his first assay will be on the Gold Coast where he anticipates success and says he hopes he shall be able to cheer the despondent Directors by a valuable and unexpected cargo.”

But it was too late. The trip never took place. On 30 August 1792, a ship arrived from England carrying with it letters containing Alexander Falconbridge’s dismissal. He bore the news with calmness and fortitude, saying he would never return to England.

For the whole of the autumn there is no letter and the next is dated 28th December. Anna Maria unleashes her fury over Alexander’s sacking.

“….…the Directors accused Falconbridge of not extending their commercial views and wanting commercial knowledge” – a fact, she agreed, may be well founded – “Falconbridge was bred to physic and men of such perspicacity would have known how unfit such a person must be for a merchant. He was aware of it himself, but believed that through application he would have improved that little knowledge so to benefit both his employers and himself.

“They should recollect the deep deception played on him. He left England with independent and unlimited powers which were restrained immediately on our arrival …….…thus bridled with the reins in possession of men who considered commerce only as a secondary view of the Company and who negatived every proposition he made…..”

“Two days before his dismission came out he was in the act of preparing matters for the trading voyage I mentioned in my last. I am certain it (his dismissal) came as a mortal stab to him. He was always addicted to drink more than he should: but after this as a way of meliorating his feelings he kept himself constantly intoxicated. A poor forlorn remedy you will say, however, it answered his wishes which I am convinced was to operate as a poison and thereby finish his existence. He spun out his life until the 19th instant [19th December] when without a groan he gasped his last.”

Alexander Falconbridge was only thirty two years of age.

It was a wicked injustice and Anna Maria needed to have her say. But she was nothing if not honest. She continued……

“…….I will not be guilty of such meanness as saying I regret his death. No! I really do not. His life had become burthensome to himself and all around him and his conduct to me for more than two years was so unkind ….as long since to wean every spark of affection or regard I ever had for him. This, I am convinced, was his greatest crime. He possessed many virtues: an excellent and dutiful son and a truly honest man were conspicuous in his character.”

A few days after Alexander died Anna Maria was visited by a representative of the Company who demanded the return of “his uniform coat, sword, gun, pistols and a few other presents that the Directors had made him…….” This was exceptionally petty. The widow tossed her head, “which I gave up, they being of no use to me.”

Alexander lies buried in an unknown grave. Three weeks after his death Anna Maria married Isaac du Bois.[9] The happy couple agreed to keep the wedding secret until the 21st January 1793, but the parson told everyone he met! (Under prevailing customs Anna Maria would have been expected to go into mourning for a year. If this delay in the announcement was meant to save face it is odd that it was only for a couple of weeks.)

The final letters and pages from Anna Maria’s Journal detail the huge upheavals taking place within the management of the settlement. The Committee of eight was disbanded in its turn and John Clarkson was set to rule with two assistant Counsellors, only one of whom, Mr Dawes, ever materialised. This man was universally disliked.

“He was a subaltern of the Marines and the prejudices of a military education [were] heightened by his having served time in Botany Bay.”

Clarkson in his turn was dismissed by the Company. Even King Jemmy, not one usually noted for sentiment, was among those who wept openly at his departure. Dawes was promoted. Among other employees scapegoated, Charles Horwood, Anna Maria’s brother, was let go “without explanation”, and so was her husband, Isaac du Bois.

Before Isaac and Anna Maria left for home, old King Naimbanna died as did the boy Prince, whose death occurred the day after his return from England.

Mr & Mrs du Bois sailed from Sierra Leone on 9 May 1793.

In London, with difficulty, Anna Maria took on the Sierra Leone Company. She was convinced she was owed money. With persistence she obtained an audience with Henry Thornton, who, so effusive the last time they met, had been particularly elusive. The Company alleged that Falconbridge kept no books, which was untrue, but when the lie was exposed the paperwork had (conveniently) gone missing. The Company alleged that she owed them money – she was particularly incensed that they tried to charge her for the £50 they had awarded her to buy presents for the King and Queen. Falconbridge, she said, had made a will. This too was lost or never existed. Anna Maria got nowhere of course. She had never intended to publish the letters, but did so in order to denounce the Company. It is hard to remember that she was still a young woman only twenty four years of age.

Francis Blake du Bois, son of Isaac and Anna Maria was born on 17 December 1801 and was baptised at St Martin the Fields the following 18th November. They were still living in London in 1805 as is known from a sad obituary in The Sun, 12th March that year. “At the house of Isaac du Bois esquire in Fludyer Street, Westminster, Mr John du Bois Younger, aged 19 years, nephew of the above gentleman and son of the late Thomas Younger of Wilmington, North Carolina.”

But then came manna from Heaven. On 17 August 1807, the Hampshire Chronicle published ‘Proceedings in the House of Commons’ with the news that His Majesty had been graciously pleased to order the sum of £5,000 to be awarded to Isaac du Bois, Esquire, an American loyalist, in consideration of the losses sustained by him in the service of the country, during the American war.

According to her Wikipedia entry Anna Maria du Bois died on 7 July 1835 in New York. Descendants of the du Bois family live in the Virgin Islands to this day. Perhaps one of them will write to me…I would love to know the further adventures of Anna Maria……

—————————————

Note. I came across Alexander Falconbridge when researching “Black Bristolians”, but I was introduced to Anna Maria by an Australian correspondent, Valerie Price-Currer, whose direct ancestor is another Alexander Falconbridge. This account would not have been possible without Valerie’s original research plus the wonderful transcript posted on-line by the author Mary Louise Clifford. To both women my very grateful thanks and apologies if I have acted out of turn.

A similar article to this one appeared on my “other” website, see “Falconbridge” in Bristol Family History, December 2011, which has details of Alexander’s brothers who lived locally. I believe that all four Falconbridge boys were of Scots descent, born in Prestonpans, but I cannot say why they came to Bristol. I was as surprised as anyone when I read my own previous account again and saw that I had found Isaac du Bois’ first marriage!

Sierra Leone, is a republic in South West Africa, capital Freetown. About 2% of the population is “Krio” – (possibly from “Creole”?), descendants of freed African American and West Indian slaves. Krio is the most widely spoken language across Sierra Leone, spoken by 97% of the country’s population.

References

[1] Christopher Fyfe, Biographer, historian, Sierra Leone.

[2] Quoted //spartacus-educational.com/USASfalconbridge.htm (not much to choose between two equally abhorrent beliefs.)

[3] This would have been the Third Fleet, part of which sailed Feb. 1791

[4] Also spelt Bunce, Bence, Bense

[5] Originally deriving from Portuguese. A discussion between rival groups who generally do not speak each other’s language.

[6] Pa or Ma is a sign of respect

[7] 10 shillings and sixpence sterling

[8] Name mis-spelt “Grenville” in the parish register. Sharp is celebrated for his championship of Jonathan Strong, a young black slave from Barbados. Strong had been so badly beaten by his master, David Lisle, that he was left almost blind. Lisle had then turned him out into the London streets as “useless”. The severity of his injuries required hospitalisation for four months, paid for by Sharp and his brother. When Strong left hospital the Sharps found him work as an errand boy with a Quaker friend. Lisle saw him working and recognised him as his ‘property’, so made plans to sell him to a plantation owner, James Kerr, for which he employed slave-catchers. Once again Jonathan was rescued by Sharp, and was then taken to court by David Laird, a West India captain who claimed Strong belonged to Kerr and produced a bill of sale. Lisle then challenged Sharp to a duel. Sharp consulted lawyers and was aggrieved to find that according to the current law, a slave remained the property of his master, even on English soil. Kerr persisted with his claim and the matter went through eight court cases. Kerr was eventually made to pay substantial damages for wasting the court’s time. In the intervening years Lisle bowed out of the proceedings. Jonathan Strong died aged 25, but had at least spent five years as a free man.

[9] 7.1.1793

Leave a Comment