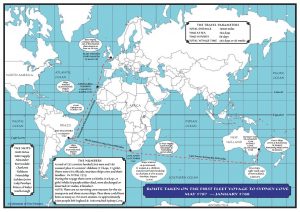

Mary Kennedy of Baptists Mills in Bristol is one of an elite group of people who made landfall at Sydney Cove in January 1788. They numbered approximately 1,373 persons, consisting of convicts, male and female, a few children, officials, marines and their wives and seamen. The voyage is known to history as ‘The First Fleet’.

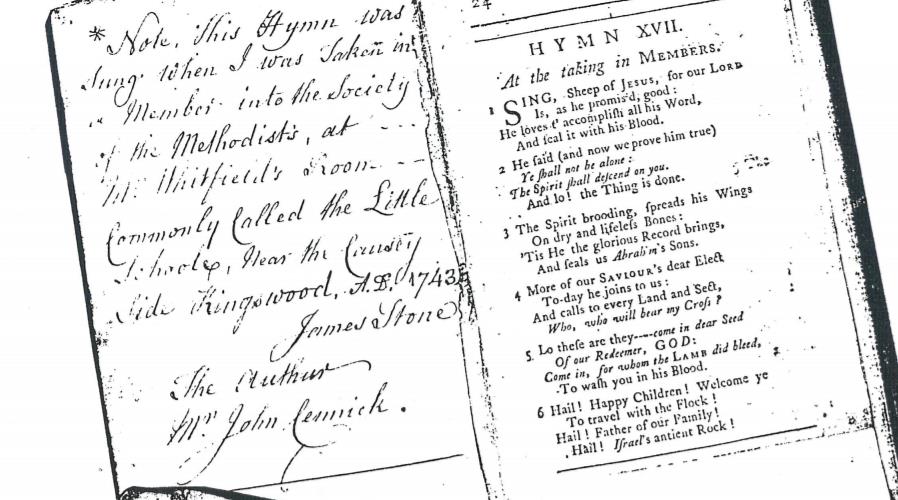

Mary was born on October 27, 1764, the daughter of James Stone and his wife Anna. Mary’s father James Stone, a collier, was a convert of John Cennick, a young evangelist, who had been drawn to Kingswood (then part of Bitton) by the missionary work of George Whitfield and John Wesley. Their novel idea of preaching in the open fields to the “ignorant” colliers led to “the Great Stir”, of 1739/40 which brought Methodism to Kingswood and thence to the World. Cennick’s devotion to Wesley palled and when he fell out with his mentor, he gathered his own followers around him. James Stone became a member of the Society in 1743 at George Whitfield’s schoolroom in Kingswood. On 3rd April the same year James married Cennick’s sister, Anna at Yate.

James and Anna had eleven children, including Anna Maria, Sarah, George, James and Rosina. Mary was probably the youngest surviving child. Sadly she was not quite three years old when her mother died aged 45. James took a second wife, Lucy, and several more children were born.

No specific details of Mary’s early years at Baptist Mills have survived, but it seems likely she grew up quietly within her devout family group. Her husband to be, John Kennedy may have been born in Bristol (at St Michael’s on the Mount) in 1752, but his military record shows that he was a Marine belonging to Captain John Shea’s Company (the 58th) at Plymouth.

The Marines were a division of the Royal Navy, a military force aboard ship, required to support naval operations, take part in raiding parties ashore in foreign parts, but primarily there to maintain discipline. Given that a number of the crew were likely to have been pressed into service, mutiny was always a possibility.

The uniform of a marine at this time was indistinguishable from a soldier of a foot regiment and John would have worn the ubiquitous red coat with white facings. His usual headgear was a tricorn hat. For shipboard duties he put aside his red coat which would become easily stained, and wore “slops”, similar to those worn by the sailors, though full uniform was required for guard duty, when on watch, and when the dread order was given “Fall in all hands to witness punishment.”

There has always been something about a man in uniform – and quite possibly Mary Stone was bowled over when she met John Kennedy. Perhaps she was “in service” in Plymouth at the time, a fate not exclusively reserved for the poorest girls, but as no record of their meeting or official marriage entry[1] has currently been found, it is impossible to speculate further.

During the 18th century, the number of crimes punishable by hanging rose to about 200. Some of these, such as treason or murder, were serious crimes, but others were minor offences. For example, the death sentence could be passed for picking pockets, shoplifting or stealing food. Though the ultimate punishment might be carried out, in many cases the sentence was commuted to transportation “beyond the seas” for a length of time which varied between seven years and life. There was no regular prison service; local gaols and lock ups existed only as holding pens until a trial could be convened (quarter sessions or assizes), where guilt or innocence was established; if the verdict was Guilty, the sentence could be carried out with a journey either to the scaffold or to the nearest port. Before the loss of the American colonies transportation had been to the plantations of Virginia and Carolina but when the war with the infant America was finally lost in 1783, this was no longer an option. An alternative destination – Africa – had been tried, with disastrous results: almost everybody died of disease. The continent of Australia, “discovered” by Captain Cook in 1770, though so far away as to be outside the comprehension of most people was the only possible alternative. Criminals still continued to be sentenced to transportation, and in the interim were kept, sometimes for years, aboard prison hulks, moored in the harbours of major port cities. Whilst they languished awaiting their fate, a fleet of eleven ships was commissioned and fitted out for the voyage. The convicts, male and female, were to be the workforce, used to build the first settlement in this new part of the Empire and to form a white under-class.

The place was believed to be largely empty of people. So that was all right then. All systems go.

The Fleet was mustered and over the coming months was kitted out for the voyage. When it dawned on the convicts that they would not be going to America, but to this unknown land, from which no-one was likely to return, there were two major mutinies[2], and some prisoners even requested that they should be hanged and get it over with.

And so……we next come across Mary, now Mrs Kennedy. She had drawn lots and been among those lucky wives chosen to accompany their husbands, (much despair among the disappointed ones); she was about to embark, with John, on the great adventure which defines her life: a voyage to Australia.

On 13 May 1787 the Fleet sailed out of Portsmouth. Their first ship was the Prince of Wales, one of the newest vessels of the Fleet, with 49 female convicts and one solitary male, George Youngson, who accompanied his sister Elizabeth. A large majority of those marine wives who had been allowed to travel with their husbands were accommodated on this ship. It seems likely that it was considered a soft berth.

On 13 May 1787 the Fleet sailed out of Portsmouth. Their first ship was the Prince of Wales, one of the newest vessels of the Fleet, with 49 female convicts and one solitary male, George Youngson, who accompanied his sister Elizabeth. A large majority of those marine wives who had been allowed to travel with their husbands were accommodated on this ship. It seems likely that it was considered a soft berth.

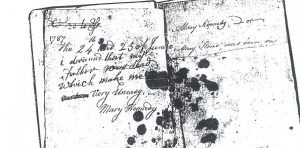

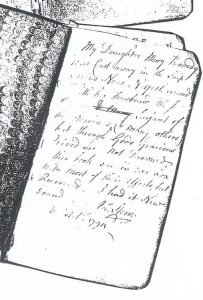

Mary carried with her a small hymnal which she had inherited from her maternal grandmother, Ann Cennick. It contains several annotations which appear elsewhere in this account but the only one written by Mary herself reads:

1787 The 24th and 25th of June

i dreamed that my Father was dead

which make me Very Uneasy.

Mary Kennedy”

The Hymn Book Mary Kennedy took with her on the First Fleet to Botany Bay

By the time Mary penned these words the convoy of ships had left Santa Cruz on Tenerife and were crossing the Atlantic bound for Rio de Janeiro. One can only believe that Mary, so far, was somewhat underwhelmed by the whole experience.

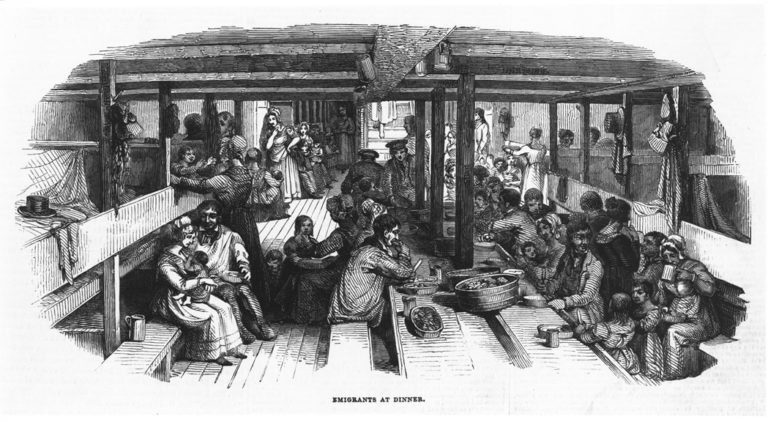

She would not have been allowed to sit around doing nothing during the voyage. Soldiers’ wives among those few who were chosen to go on campaign were put to use in a variety of tasks, sewing, mending, cooking, tending the sick, and I cannot imagine life aboard ship for the marine wives would have been any different.

The Prince of Wales was lucky enough to have a chronicler aboard, another Marine Sergeant, James Scott, who kept a diary of the voyage.[3] On 24th June, the day before Mary’s uneasy dream, he reports that two marine privates, Robert Ryan and Arthur Dougherty were charged with insolence and disobeying orders on HMS Sirius, the flag ship. Dougherty was acquitted, but Ryan was sentenced to 300 lashes though he collapsed after 175. The following day, the 25th he was sent aboard the Prince of Wales presumably to recuperate, probably nursed by the marine wives. Mary must have been aware of this grim punishment ritual. It is no wonder she felt uneasy.

On 14th July they crossed the Equator, when first-timers were subjected to initiation rites, involving total immersion in a barrel of water by King Neptune and sundry mermaids. It was a chance for everybody to dress up, dance and let off steam, though not the convicts. The ceremony could easily degenerate into a free for all. According to Scott, Sergeant Kennedy went too far. He got “thoroughly drunk” and after abusing several people, he

“Jumped Down the Main Hach Way Upon My Wife Which As She Sat at Work Just By the Lader Which Caused a Great Fright. And Like Wise Hurted her Greatley.”

Kennedy spent two weeks in iron leg cuffs, and was reduced to Private by Court Martial. Given the harsh retribution meted out to others, he was let off lightly.[4] Though I suspect Mary was less than pleased, not only because of John’s mortifying antics, (her upbringing would have made her put great store by being ‘respectable’) but more especially because part of the sentence was removal of them both to the Alexander, a much harsher environment with all male prisoners and only three other wives, whereas on Prince of Wales she had fourteen women for company.

The Fleet landed in Rio de Janeiro on 7th August where they remained for about a month. The ships were thoroughly cleaned and old clothes burned to get rid of lice and fleas. Scott’s wife Jane recovered well enough to go ashore in Rio and on 29th August gave birth to a healthy girl which she named Elizabeth.

The Kennedys left Rio for the Cape of Good Hope in the Alexander, the largest transport in the Fleet. A former merchant ship, built c1783, she was a barque with three masts and two decks. There had been sixteen deaths aboard from fever due to foul water in the bilges even before the ship left Portsmouth. Along with a heavy marine guard, the few wives and children, she carried 30 crew and 195 male convicts, fifteen of whom died on the voyage.

Between Rio and the Cape a plot was discovered. Five convicts and several members of the crew allegedly planned to overpower the guards and take command of the ship, intending to depart at the first landfall. Two of them, Philip Farrell and Thomas Griffiths were removed to HMS Sirius for punishment, and afterwards to the Prince of Wales, once again presumably to the tender care of the marine wives. The Fleet landed at Table Bay, Cape Town on 13th October.

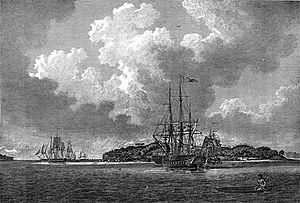

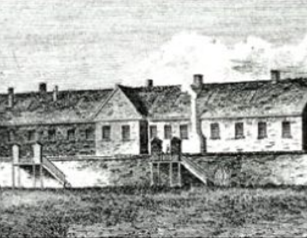

After passing Tasmania on 16 January 1788, the Commander, Arthur Phillip, transferred from his Flagship Sirius to the tender Supply and in company with the three fastest transports under John Shortland in Alexander sailed ahead as the advance party, being the first ships to reach Botany Bay on 18th & 19th January 1788. On 22nd January Governor Phillip sailed north to Port Jackson with a small expedition party. There he chose a sheltered site for anchorage which he called Sydney Cove.

Alexander arrived there on 26 January 1788 and began to unload her convicts.

An engraving of the First Fleet in Botany Bay at voyage’s end in 1788, from The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay.[8] Sirius is in the foreground; convict transports such as Alexander are depicted to the left.

John Kennedy who had been reinstated to Sergeant, was again demoted in April 1788, with his rank restored the following September. His erratic career continued in 1789 when Sergeant Scott was again on hand to record:

“Sidney Cove, Port Jackson, Jany 20th Tuesday: Jno. Kennadey. Serjt. Reduced to privt by the Sentince of a Court Martial.”

Unfortunately he did not state the offence John committed on this occasion.

In May 1789 with the food in the colony rapidly running out, Sirius was despatched to Cape Town for supplies but returned with less than four months’ worth of flour. Drastic measures were necessary if everybody was not to starve to death.

Part of Governor Phillip’s remit was to start a twin settlement on Norfolk Island, across the Pacific, midway between Australia and New Zealand. Sharing out the dwindling supply of food, he ordered 280 of the convicts and marines, among them Mary and John Kennedy, still a Private, to sail to the island in Sirius where farming conditions were believed to be favourable. They were to unload the passengers, stores and equipment, then the plan was for the ship to continue to Canton to stock up and return to both settlements with much needed food and supplies. The scheme came to nothing on 19 March 1790 when disaster struck. Sirius foundered on a reef on the island’s rocky foreshore and broke apart. Most of the scanty provisions they had brought with them and many of their effects were lost.

Part of Governor Phillip’s remit was to start a twin settlement on Norfolk Island, across the Pacific, midway between Australia and New Zealand. Sharing out the dwindling supply of food, he ordered 280 of the convicts and marines, among them Mary and John Kennedy, still a Private, to sail to the island in Sirius where farming conditions were believed to be favourable. They were to unload the passengers, stores and equipment, then the plan was for the ship to continue to Canton to stock up and return to both settlements with much needed food and supplies. The scheme came to nothing on 19 March 1790 when disaster struck. Sirius foundered on a reef on the island’s rocky foreshore and broke apart. Most of the scanty provisions they had brought with them and many of their effects were lost.

Fortunately everyone made it ashore including Mary Kennedy……as her proud father would later write in the hymn book:

“My Daughter, Mary Kennedy was Cast Away in the ship Sirius Near Norfolk Island with her husband Mr J. Kennedy Serjeant of the Marines and many others but through God’s Gracious Providence Not Drowned. This book was in her box with most of their effects but recovered. I had it new bound. “

“My Daughter, Mary Kennedy was Cast Away in the ship Sirius Near Norfolk Island with her husband Mr J. Kennedy Serjeant of the Marines and many others but through God’s Gracious Providence Not Drowned. This book was in her box with most of their effects but recovered. I had it new bound. “

“Ja: Stone, Bristol, 1794”

We can see why some of the pages are so blotched.

The colonists were stranded on the island, eking out what food they had managed to salvage by catching ‘Mutton birds’, the poor creatures remarkably tame, and also eating their eggs, as well as vegetation they called cabbage trees. Jacob Nagle, an American able seaman, a First Fleeter of Sirius wrote a remarkable journal of his life and adventures. He recorded:

“On the next Saturday our last provisions was to be served out, one half barrel of flower. The birds were destroyed the cabbage tree was likewise all gone and as for fish it was very uncertain ……even if we could ketch them it would not supply one quarter of our number.”[5]

On 7 August 1790, two ships were spied. These were the Surprise and Justinian, which had arrived at Sydney Cove as part of the Second Fleet. They brought much needed supplies, but also another thousand mouths to feed. A decision was taken to bring some of the convict women to Norfolk. [6] The castaways rowed out in cutters, but transferring the people from the ships proved hazardous in the heavy surf. Nagle recorded:

“six seamen, and one woman drownded, boat and five went into the whirlpool. Two quartermasters was got on shore and buried on the island….what was surprising those two men, petty officers and good seamen always dreaded being in a boat.” [7]

William Hunter, a fellow crew member of Nagle’s saved one woman and her child, holding them in his arms until they got ashore.

John and Mary Kennedy left Norfolk Island in November 1791 when the detachment of marines was taken off. Three of the marines, John McCarty, Thomas Bishop, and William Mitchell who had fathered children with three convict women on the island left the service and went back to the island where they rejoined their partners.

On 18 December 1791 HMS Gorgon sailed from Port Jackson with samples of animals, birds, and plants from New South Wales and taking home the last company of Marine Corps which had accompanied the First Fleet. Among them were John and Mary Kennedy with more noted companions, the Marine Commander Robert Ross, the astronomer William Dawes and the diarists Ralph Clark and Watkin Tench. Of their departure, Tench said, “we hailed it with rapture and exhilaration”.

At the Cape of Good Hope, Gorgon took on board William Allen, Samuel Broom, Mary Bryant and her daughter Charlotte, Nathaniel Lillie and James Martin. These were the survivors from a party of convicts who In March 1791 had absconded from New South Wales in Governor Phillip’s six-oared cutter. After a voyage lasting 55 days the group landed at Kupang in West Timor. Their epic journey of 5,000 kilometres has been compared with William Bligh’s similar passage after the Bounty Mutiny of two years before which had also ended on Timor. Sadly, the fugitives were apprehended, and Mary lost one of her children, and her husband, William Bryant, a survivor of the Swift mutiny who she had met on the prison hulk years before when they both awaited transportation. Mary enjoyed a brief celebrity when her cause was taken up by James Boswell after which she was forgotten. Then, 150 years later she suddenly resurfaced when a sample of her tea leaves – used to ward off scurvy, were found among Boswell’s papers at Yale University. But that is another story.

To add to the coincidence Gorgon also took on board ten of the mutineers from the Bounty. These men had not put to sea with Fletcher Christian but had remained on Tahiti where they were arrested by the captain of HMS Pandora. On the way home the Pandora was wrecked and several of the captives who were kept below decks, heavily ironed, were unable to escape. Of the remaining ten, six were exonerated for the mutiny, though the other four were hanged.

As to the Gorgon, during the last leg of the journey, many of the children on board, including Mary Bryant’s daughter Charlotte, died of heat and illness.

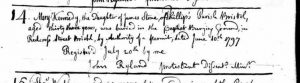

John was discharged from the service at Portsmouth in June 1792. Nothing is known of him thereafter though presumably he came back to Bristol with Mary. We know that her proud father had the hymn book rebound in 1794, and he probably talked of her exploits to anybody who would listen. Otherwise she returned to obscurity and nothing is known of her until she died on 10 June 1797 at the age of thirty three. She was buried in the Baptist Burying Ground in Bristol.

[1] The only reference to the marriage is in the hymn book.

[2] The “Swift” & “Mercury” Mutinies. Watch this space.

[3] Scott’s diary is usually on line, but currently it has been withdrawn for updating. I have relied on the few snippets available. Acms.sl.nsw.gov.au

[4] See above. My Australian correspondent, deceased many years ago gave me a slightly different version.

[5] The Nagle Journal. Ed John C. Dann.

[6] The women had arrived at Sydney Cove aboard the “Lady Julian”. They included Shuke Milledge of St George, and Jane Fidoe and her two daughters of Temple.

[7] Nagle, ibid.

Blog Comments

Madeleine Fletcher

7th June 2021 at 7:32 pm

Fascinating! I’m looking forward to reading more articles on this amazing website!