Family History research often leads to something entirely unexpected. In 2014, my first cousin Jack GREGORY was due to attain a milestone birthday. What to give a 90 year-old-man? The majority of us who have survived to “a certain age” have everything we could possibly want in the realm of “stuff” and more of the same is often a nuisance. So I thought I would give him a present of “himself”. To this end I decided to research and write the outline story of his life and put it together as a booklet with a few historic family photos and some “then and now” shots of places Jack would remember. So I did the rounds: Bristol Record Office for his christening records, took a few snaps outside the graveyard of his ancestors, (the Wesleyan Chapel, Kingswood, now a scene of Gothic devastation with impossible access- for more info see the Budgetts of Kingwood Hill) and then started on the places where he lived as a boy.

I was standing in the street photographing various houses when my cheeky activity was noticed by a current resident. He asked politely “Would you mind telling me what you are doing?” My snooping could have resulted in an unfortunate “incident” but I explained that I had no sinister intentions but was engaged in family research and that many years before my aunt had lived in the house which I myself had often visited as a child. The gentleman did not say “Clear off” as he had every right to do, but called his wife, and I elaborated on my mission. The world is divided into two groups of people: the ones whose eyes glaze over at any mention of history in general, let alone family history, and those whose appetites are whetted, principally, I think, by the not – to – be missed opportunity to discuss their own ancestors. We chatted for some little while. The couple had been in the house for thirty six years having actually purchased the house from my late auntie Pollie who they recalled. It started to drizzle. They invited me inside; so far, so ordinary and yet so kind.

We were sitting in the living room sipping tea and by now had exchanged names. “Do you ever do this sort of thing professionally?” asked Liz EKNER, the lady of the house. Those days are long gone but I still cannot resist a tale. At my urging, my hostess told their family story.

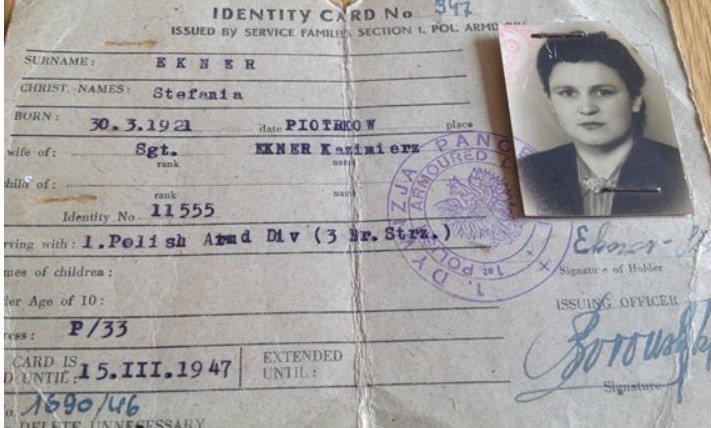

Liz, nee GRABOWSKA, and her husband Jerzy Ekner were born of Polish parents and spent their early lives in different refugee camps in England after the end of the war. They met at a family wedding and were married in 1976. Liz said she “knew everything” about her own ancestry, her father having fought with the Polish Free Forces attached to the British Army, but it was the Ekner side of the family which was intriguing, a mystery specifically regarding Jerzy’s mother, Stefania, who married Sgt Kazimierz Ekner, who was also a soldier with the PFF. They came to England where their children were born. Eventually they arrived in Kingswood, Bristol, where Kazimierz died in 1971 and Stefania in 2001.

“Between her marriage and her death we know everything there is to know about our dear Mum,” Liz went on, “but she would never talk about her early life, from her birth in 1921 until…….”

and her next words made me shudder. My stomach turned to ice……..

……..until she was liberated from Ravensbruck Concentration Camp.”

Stefania was born at Piotrkow Trybunalski, Poland, on 30 March 1921. The date is repeated on most of her documents except one, a typescript listing the camp internees which gives her birthdate as 30th June 1921. This may be simply a clerical error, though given the Nazis’ zeal for admin, the discrepancy is worth noting. The “Edited List of Polish Political Prisoners” states that her parents were called Jozef and Waleria. She was arrested for political activity and held in the transit camp at Pruszkow (Dulag 121) from 2nd to the 9th September 1944.

Following the Warsaw Rising, 650,000 Poles passed through this transit camp in August, September and October 1944. 55,000 were sent to concentration camps. They were segregated by the Gestapo and SS into categories: Aryan/Non Aryan. They came from all social classes listed by occupation: civil servants, artists, doctors, scholars, shopkeepers, blue collar workers; they included the injured, the sick and pregnant women; they were aged from infants a few weeks old to octogenarians.

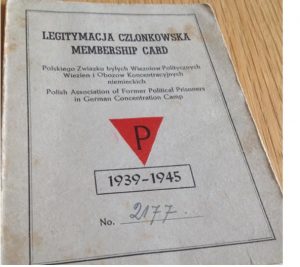

Ravensbruck was specifically a concentration camp for women. About a quarter of the women sent there were Polish, who were forced to wear two triangles, one red and another with the letter “P” for political. Their heads were shaved. Norwegian women, classed by the Nazis as “the highest rank of Aryans” (!) were spared this indignity. Soviet, German and Austrian communists were also denoted by a red triangle; common criminals: green, Jehovah’s Witnesses: lavender, prostitutes, lesbians and gipsies: black. It has been called “the banality of evil”, and nothing sums it up better than the division of the women into these chillingly bizarre subsets. By the time Stefania came to the camp most of the Jewish inmates had been transported to Auschwitz.

Her identity card. (The inside of the card is shown in the header image).

Stefania arrived at Ravensbruck on 7th September 1944 where she became prisoner number 65783. She was there for seven months. With the rapid advance of the Red Army in the spring of 1945, the SS ordered the murder of as many prisoners as possible to avoid anyone being left alive to testify. These included the British SOE Agents Cecily Lefort, Lilian Rolfe, Denise Bloch and Violette Szabo. With the Russians only hours away, those who remained, some 20,000 souls, were ordered on a death march towards Northern Mecklenburg. Two thousand sick and dying prisoners were still in the camp when the Russians arrived. They rounded up those guards who had not escaped. At the Nuremburg War trials sixteen camp officials charged with crimes against humanity were sentenced to death. The chief wardress during Stefania’s time, Dorothea Binz, had toured the camp brandishing a bull whip in the company of an unleashed German Shepherd dog. She would select a woman at random and kick her to death or order her to be killed. Another guard, Vera Salvequart was a trained nurse, who oversaw thousands of deaths in the gas chambers. Both Binz and Salveguart were hanged by the British public executioner, Albert Pierrepoint, in 1947.

It is not surprising that Stefania was so scarred by her horrific experiences that she refused to talk about them. Of her previous life all she would say is “my mother and father are dead. My sister fell under a train. My brother was shot.”

Stefania Biegarczyk & Sergeant Kazimierz Ekner. Wedding Day in Germany, 1945.

Liz and Jerzy who are bi-lingual in Polish and English, went to Piotrkow several years before I met them. They located the parish priest there (they are Catholic) and searched for Stefania’s baptismal records and those of her siblings. They found no reference to the names Biegarczyk or to SIEJEK, another name, apparently an alias, by which Stefania was sometimes known. Their niece Tracy has taken up the challenge and has uncovered more information, specifically camp records on which Stefania’s name appears, but so far there is nothing to supply a clue to the missing years. Liz says she feels “sure that somewhere, there is someone still alive, who knew Stefania, who knows something of what really happened. That there must be a relative out there…..”

Piotrkow is some 80 miles from Warsaw, about two hours by train. Why did Stefania leave there to go to Warsaw and thus become caught up in the Rising? Was she conscripted or did she go to Warsaw of her own accord? What terrible fate befell her parents, her brother and sister?

I have not been able to find any of them on the LDS, (otherwise the Mormons) index. (www.familysearch.org) Why did Liz and Jerzy find nothing in church records? What is the meaning of the alternative name “Siejek”? Did you know Stefania? Or others like her?

A version of this blog was published in teh Bristol Post on 23 May 2023.

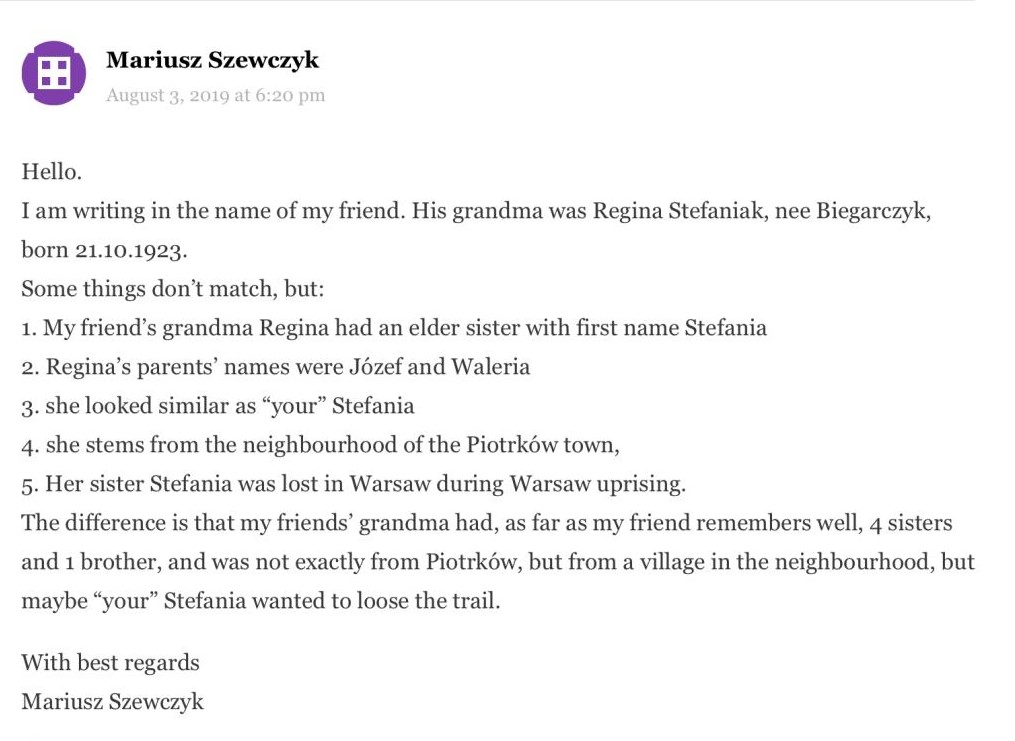

The above reply, received following the publication of my original article generated some excitement. It is quite possible that the names Josef/Jerzy could have been misread or misrembered. Stefania may only have spoken of one sister and one brother. Unfortunately the writer failed to respond to further communications. I appeal to him to write again or indeed anyone who has any information.

Bibliography:

“If this is a Woman – Inside Ravensbruck: Hitler’s Concentration Camp for Women” by Sarah Helm.

From Wikipedia:

From the first months of the war, Piotrków was a centre for underground resistance. From the spring of 1940, it was the seat of the district headquarters of the Armia Krajowa, or Home Army. In the summer of 1944, the 25th Infantry Regiment of the Home Army was formed in the district; it was the largest military unit of the Łódź Voivodeship, and fought against the Germans until November 1944. In the city and district, there were also other partisan groups: the Military Troops (connected with the Polish Socialist Party), People’s Guard and People’s Army (Polish Workers’ Party), Peasants’ Battalions (Polish People’s Party), the National Military Organization and the National Armed Forces (National Party). After the fall of the Warsaw Uprising, the headquarters of the Polish Red Cross was temporarily located in the local Royal Castle from October 1944 to January 1945.

An article similar to this one appeared in a past Journal of the Bristol & Avon Family History Society.

Leave a Comment