The following article was originally printed in the September 2016 edition of the South Bristol Voice.

“This may seem a silly question,” one of the mums said at the Grand Opening of the playground in Perrett’s Park on April 2, 2015, “but why is it called Perrett? Is it after somebody?”

Such is the fleeting nature of celebrity. The conversation ended as the currently famous Don Cameron arrived and began to tinker with one of his balloons. A crowd gathered round as the great balloon slowly but quietly inflated and drifted silently a few feet upwards on its ropes. A cheeky dad in the front row said it was his daughter’s birthday and asked if she could have a ride. She was hoisted up into the balloon’s basket.

Such is the fleeting nature of celebrity. The conversation ended as the currently famous Don Cameron arrived and began to tinker with one of his balloons. A crowd gathered round as the great balloon slowly but quietly inflated and drifted silently a few feet upwards on its ropes. A cheeky dad in the front row said it was his daughter’s birthday and asked if she could have a ride. She was hoisted up into the balloon’s basket.

Seventy-odd years ago it was a different, more sombre, story. There were other balloons then, barrage balloons, sinister dark shapes protecting the city from the Luftwaffe.

Each balloon was held fast to the ground by a steel hawser, strong enough to destroy any aircraft that collided with it. The cable was locked into heavy metal rings set in reinforced concrete. The rings were made to last and so they did, re-discovered during the excavations for the playground.

Mr Charles Rose Perrett was, in his time, certainly somebody famous, in his adopted city of Bristol at any rate. He originally had the idea of a park for Knowle before the First World War. On February 17, 1914, he stated: “We do not want a large place … we would be thankful for small mercies.”

The scheme was sadly overtaken by events and it was not until New Year’s Day 1923 that a James Ellis of 240 Bath Road wrote to the Western Daily Press suggesting that the local councillors, who included Mr Perrett, should try to secure land at Crowndale and Bayham roads before it had been snapped up for building. The letter may have been a ruse to engage the media, for it is likely to have been discussed round a family dinner table; Mr Ellis was Cllr Perrett’s half-brother.

Thus, that spring, Charles Perrett managed to obtain an option on 10 acres, formerly part of the Greville Smythe estate at Bayham Road and Sylvia Avenue, two thirds of which was under cultivation as allotments. Mr Perrett stated that 18,000 people would be served by the park as a place of recreation and offered to donate £500 out of his own pocket. The council considered the proposal and the cost was calculated:

- Cost of 10 acres of land £1,000

- Fencing £900

- Layout £1,000

- Cost of abutting road: £2,135

- Sub-total £5,035

- Less £500 from Mr. Perrett (£500)

- TOTAL: £4,535

The land was formally acquired in November 1923. In April 1925, the final total was said to be £5,100, which included a new portion of road. Mr Perrett had provided six seats for the elderly and it was hoped that a fountain would be installed in the near future.

The Country Boy: 1843-1873

Charles Rose Perrett, was born in very poor circumstances in the small hamlet of Marston, near Devizes in Wiltshire, born to a single girl, Eliza Perrett, aged 17. Eliza lived with her widowed mother Mary and younger sister Maria, two years her junior.

Marston even now is a very small place, boasting a post box, a phone box, a bus stop and a village green with a duck pond.

Baby Perrett came into the world on January 6, 1843. Unlike most other children of the time, he stood out by having two Christian names. A middle name, if used, was generally the mother’s or grandmother’s surname or was included to flatter a rich relation. The latter category could, at a pinch, apply to young Charles, as the name ‘Rose’ is likely to have been his father’s surname.

In the small world of Marston-Worton we have to assume that everybody knew of Eliza’s ‘trouble’ and two suspects immediately enter the frame. They were brothers, local farmers, James and Job Rose, and though I should know better than to give a dog a bad name, the younger of the two, Job, seems to me to be the more likely candidate, though there is not one jot of proof.

As a leap in the dark, I suggest that Mary Perrett and her daughters laboured on the Rose farm and that at some time in 1842, Eliza had become pregnant by one or other of the brothers, who perhaps had even, horrible thought, exercised a rustic droit de seigneur.

At the very least, Job Rose had a reputation. In the year before Charles Perrett was born Job had appeared at the Devizes Petty Sessions charged with an assault on one of his neighbours, Thomas Potter.

As reported in the local press, “As Potter was going into his field, he met Rose on horseback who gave him the customary salutation “Good morning”.

“Fine morning,” Potter replied.

“And you are a fine fellow,” Rose said, sarcastically, “and a shabby fellow too.”

Having thus departed of his good manners, he quickly parted with his temper too. He descended from his horse and having tied the animal to a tree, made up to Thomas Potter, who a few minutes before he had wished “Good morning” and dealt him three or four blows about the face and head.”

Job Rose said that if the magistrates knew of the circumstances which led to the blows they would deal with him leniently, to which he received the reply: “But you must not take the law into your own hands.”

The magistrates found the case proved and Job Rose was fined 10 shillings plus costs.

It is easy to picture the pair: Rose, burly, red-faced, blustering, and the little man, Potter, at first indignant and then reeling with shock at the onslaught. What were the extenuating circumstances to which Rose alluded?

I hazard a guess that Job was the subject of village gossip, for Charles Perrett was not Eliza’s first child. She was about four months pregnant when the census man called in June 1841. Tragically, baby Lydia was buried at just four weeks old. Eliza was barely 16. There is no indication that either of the Rose brothers fathered Lydia.

In 1845 Eliza was married to a farm labourer, Solomon Ellis and two-year-old Charles came as part of the package.

In the census of 1861, Solomon was still an ‘ag. lab’. Their elder son Joseph, 11 was already a farm labourer, and there was a brother, Henry, 4. Charles Perrett, 18 and also working as an ‘ag. lab’, appears at the bottom of the family list.

One reason Charles Perrett gave for leaving home was his dissatisfaction with his wage of seven shillings a week and later, when his political career was taking shape, his first cause was the poor wages paid to agricultural labourers. Nevertheless I think that possible family friction also contributed to his decision to leave Marston. Thus, one summer morning at 3.30am he set out on foot for Bath. His dream had been to join the police force but when he arrived at the station he was told to his disappointment that there were no vacancies, so he continued on to Bristol where he was taken on by a Bedminster brewery, James & Pierce’s. After this he worked for a sack hiring firm. In 1864, he was able to send for his sweetheart, Mary Ann Edwards, and they were married at Holy Trinity, St Philips, on September 4 that year.

Mary Ann was the child of a large family of impoverished Wiltshire farm labourers. Like almost every young girl of her class, she went ‘into service’ at an early age and by 1861 was in a household in Worton, where she met the young farm labourer, Charles Perrett. At the time of their marriage he was living at Clarence Place and she was at Melbourne Terrace. Both signed the register with good, neat signatures. I expected to see a space where the name of Charles’ father should appear, but it read: ‘John Perrett, labourer’. Charles would not be the first to tell a little white lie to save face.

By 1871, Charles was working as a warehouseman, probably at the sack hire enterprise, and living with Mary Ann at 64 Regent Street, St Philip’s. Unfortunately, the marriage was childless. If this had not been the case, Charles may not have turned his considerable energy elsewhere.

The first evidence of his social conscience appears 1873 when he wrote to the Western Daily Press with an impassioned and well-argued letter about a subject close to his heart: agricultural labourers’ wages.

Charles had witnessed a debate at the Greyhound Hotel, Broadmead, in which it was disputed that farm labourers were poorly paid. He wrote: “I can point to scores or hundreds of similar cases now at the present time, not more than 30 miles from Bristol, men not getting more than 10 or 11 shillings per week. Indeed, many of them go to work, many of them milking &c at four in the morning, and work until 10 at night in the summer.”

From here on Charles aired his opinions frequently and it was not long before the local Liberal Party spotted a potential star.

No doubt Mary Ann still spoke of the privations her family had endured and likewise, Charles’ own memories would have been still raw. His step-father Solomon Ellis had remained an ‘ag. lab’ and had been recorded so in 1871, along with Charles’ step-brothers, Joseph, Henry and William, all ‘ag. labs’.

The Bristol Philanthropist, 1873-1925

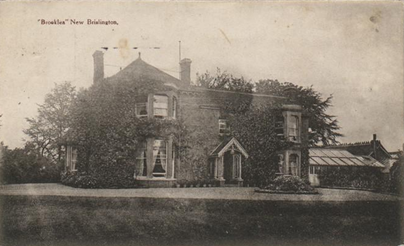

In 1881, ‘Charles R. Perrett’ aged 38, was living with Mary Ann at Marston House, Stanley Hill, Bedminster. One cannot help but believe that Charles took pleasure in naming his house. Charles was now a foreman manager, and they had a servant. Mary Ann had a job, as a “shop woman”.

He had joined the Liberal Party, the YMCA and a Friendly Society, the Ancient Order of Foresters. He was made an Honorary Member of Totterdown Men’s Adult School and also later joined the Bristol Moonrakers, a gathering of native Wiltshiremen. His name appears frequently in the local press in the 1880s and 90s, attending these organisations. He championed political campaigns, such as increased wages for the labouring poor and better roads, and individuals fallen on hard times.

By 1891 he had moved to 126 Wells Road, and had become a white collar worker in the insurance industry, first with ‘the Pru’, the Prudential Assurance Company and then with the Sun Fire Assurance Co. He was still an agent of the latter company at the time of his death. He had recently been elected to Bedminster Parish Council.

He did not confine himself to parochial affairs and in 1900 he took up the cause of the welfare of our armed forces fighting in South Africa and for their wives and children. One letter to the Western Daily Press was headed ‘The Relief of Mafeking’:

“Sir: I hear that there is a fund to be raised to help those that have been shut up in Mafeking since October 11th 1899 to take a trip to the sea to help them in some way. Will you please receive 21 shillings as a special thank offering for the relief of Mafeking, good little Baden-Powell and all that have helped him in the noble defence.”

Charles had stumbled on a new calling, that of philanthropist. At the time it was fashionable for the press to publish the names of those who donated to worthy causes, along with the sum of money involved. Though some people preferred to remain anonymous, this was not Charles’ way.

By 1901, the servant had departed and had not been replaced. Mary Ann, aged 59, was no longer in paid work. On only a few occasions she is recorded as being with him when he was out and about most nights at his clubs and societies. He stood for Bristol city council in 1906 and 1907 but was defeated both times.

In January 1913 the National Insurance Act was passed which allowed a grant to each new baby. The first to benefit in Bristol was a child called Walter Coles, of 10 Devonport Street, Bedminster. “Mr. C. R. Perrett, an ardent Liberal and admirer of the Act” announced his own award of one guinea, to go to the first two claimants of the new maternity benefit. Mrs William Cashman of 8 Paradise Cottages, New Cut received 13 shillings.”

On September 4, 1914, Charles and Mary Ann celebrated their Golden Wedding anniversary at the Totterdown YMCA attended by 300 guests, mostly from religious and political circles. Charles was praised for his philanthropic work and received an illuminated address. The happy couple also received “a handsome inkpot” and a cushion.

From the outbreak of the First World War, one would have expected Charles to be among those banging the drum encouraging young men to join up, but he is unusually silent until April 1915 when the Lord Mayor of Bristol opened a fund on behalf of Belgium. Charles drummed up support, stating:

“The distress of Belgium among the civil population is great; the humiliation cannot be blotted out; and remembering the peace and security we are enjoying greatly through the sacrifice of gallant Belgium it should constrain many to send to the Lord Mayor’s fund as an act of gratitude.”

Mrs Perrett contributed two guineas to the fund and CRP himself, three guineas.

On November 24, Mr Perrett was holding forth with advice for the conduct of the war on the Home Front, advocating the keeping of poultry and pigs. “When I was a boy,” he said, “almost every cottager kept a pig or fowls.” He believed that “the Sanitary Authorities have been a little too particular as to where they should be kept.”

Sadly, on March 10, 1916, Mary Ann died “after nearly 52 years of happy married life, the dearly beloved wife of C.R. Perrett in her 75th year. No flowers by request.” In her will she left £1,218. 2s.5d.

In November 1917 he was co-opted on to the Bristol city council when the seat for the Somerset ward became vacant.

At the time there were 2,000 homes in the city with two or three families living in each which were unfit for human habitation. Such conditions contributed to the increase in consumption and infant mortality. CRP’s interjection in the debate was unexpectedly tart: he said “Bad tenants sometimes in a few months make a dwelling uninhabitable.”

He was soon regularly speaking in the council chamber. The plan to raise the salary of the chief constable from £800 to £1,000 per annum was “deplorable” he stated. And he went back to his old refrains, pigs and allotments. “Councillor Perrett is a man who happily practices what he preaches,” said the Western Daily Press leader on April 20, 1918, “he has got the pigs and the allotment holders are to feed them, so no waste there …”

Mr Perrett also brought to the Sanitary Committee’s attention the fact that householders in his ward did not separate food scraps from general waste. In this matter at least, he was years ahead of his time, and would certainly have approved of recycling and the present variety of bins.

In February 1919, he opposed the council spending money on “feasting” to celebrate the peace. Instead, “I would like to suggest that we build or purchase some homes in different parts of Bristol, put them in good repair and tender them as almshouses rent free to old people say 50 and upwards.”

We can only blink in disbelief that less than a century ago people of 50 teetered on the brink of old age.

Perrett’s Homes

Clearly he and Mary Ann never forgot the privations of their parents and grandparents and in 1913 they initiated the charity that was to become Perrett’s Homes.

In a letter of March 1914 he said he thought the houses costing £300 which the council was building were far too dear and suggested six-room dwellings for the working class, costing £150 each, which could be rented at five shillings a week. He stated:

“There are plenty of men getting upwards of 30 shillings [a week] living in courts who could well afford five shillings rent. What we want is to get these people out of such places and away from the many public houses. I hope the Corporation will never build more homes in flats but in rows.”

The ‘courts’ were overcrowded slums in poor areas where many families, several people to a room, lived in abject squalor. Had councils taken on board his suggestion to build in rows rather than flats, we might have been spared those concrete monstrosities, the high rises, after the Second World War.

By September 28, 1916, Perrett’s Homes were in full swing. The Western Daily Press reported that “the philanthropic schemes of Mr. C.R. Perrett are numerous and one of the most practical of these are his almshouses at Stanley Hill, known locally as Perrett’s Homes. Three years ago, Mr. & Mrs. Perrett initiated the scheme with three houses where old age pensioners or deserving poor, irrespective of religious views could live free of rent or taxes. Recently five houses were added by Mr. Perrett, housing 12 people in all. […] Mr. Perrett said his main object was to give a lead to people that he hoped would be followed when it was seen how successful his scheme was.”

After CRP’s death, Bristol Charities sold the properties at Stanley Hill and Totterdown in the 1930s. A former almshouse in Cumberland Road was acquired, named Perrett’s Almshouse. This was demolished in 1969 and the proceeds used to build sheltered housing in Redcross Street, near Old Market, called Perrett House, with a further eight flats added in 1987. Perrett’s name is still to be seen on flats at Cumberland Road and Stanley Hill.

Intermission: The Reactionary, ca 1912-1930

No man is a hero to his valet (it is said) and likewise the biographer may uncover a few unpalatable truths about his subject. Mr Perrett was evidently much loved in Bristol, and it comes like a slap across the face to record a less attractive side to his character.

He first aired his reactionary views in public (as far as I can tell) in a letter to the Western Daily Press on November 6, 1912 concerning women’s suffrage.

“Sir. After the election in the Somerset Ward last Friday, I am more than ever satisfied that 18 out of 20 of the women in the Register do not want the Vote and would much rather they had not got it. I have had 37 years’ experience in this ward and I have always found it is the greatest trouble in the world to get them to the poll. I flatter myself that I can do a good deal with the widows and spinsters in this district but on this point I have utterly failed and have almost made up my mind not to try any more. But what I want to say is that I hope the Members of the House of Commons will refuse to give the women any more votes. It will be one of the greatest mistakes if they do.”

The County Council Act of 1888 had allowed eligible women to vote in local and county elections. In fairness, Mr Perrett’s views were shared by many others, including no less a personage than Winston Churchill.

The Representation of the People Act, 1918, gave the vote to all men over 21 and, in a typically British fudge, to women over 30 provided they met the minimum property qualifications. The women’s campaign for parity with men continued. On March 4, 1924, Charles Perrett was at it again:

Sir. I should like, as a life-long Liberal to protest against the giving of the vote to women at 21 years of age. Thirty as at present is quite early enough. Very few understand or know what they are voting for.”

In 1928, women were granted the vote on the same terms as men, that is, over the age of twenty one. Game, set and match …

Mr Perrett also opposed the employment of women as police officers or as council clerks, arguing that their jobs should go to unemployed men. On February 11, 1920, in council, he said: “The Bristol police women were a laughing stock. The 12 women police cost £1,574 and were a waste of money. They paraded the streets and did very little.”

The Park Opens

There had long been a demand for a park in the Knowle-Totterdown area and the council, spurred on by Mr Perrett’s donation of £500, thus providing a cheaper option, swiftly put matters in hand, despite the fact that not everybody was happy – the 100 allotment holders, for instance, who had to be turfed off their plots. A sample of the complaints, before and after:

Mr Perrett’s Park faces north and gets the aroma from the Marsh.”

“The piece of land now known as Perrett Park should never have been purchased however cheaply it was obtained.”

“And what about the slope?”

“A perfect White Elephant!”

“A fiasco!”

“Was any ballot held before the land was acquired?”

“Unsuitable! What we want is flat ground suitable for old people to walk on!”

“It is small, inadequate for the wants of the area, and very steep: two steep sides.”

The park was nevertheless well under way by 1925 and was stated to be “very popular”. The council officially adopted the name Perrett’s Park in July 1927.

In November 1929 Mr Perrett announced his intention of donating a fountain for the park to commemorate his 88th birthday. On April 12, 1930, the fountain was switched on, with much ceremony and congratulations to the benefactor.

Sadly, it was CRP’s last public appearance. A month later he was suddenly taken ill and died on May 13, 1930. Referring to him as “TOTTERDOWN G.O.M.” or Grand Old Man, the Western Daily Press declared: “Starting life in a humble way, by thrift and carefulness, he accumulated fairly substantial means from which he gave generously to local institutions.

“For old and deserving people he provided eight houses in Stanley Hill and in addition to living rent free, the old people received a cash gift each week.

“He also had six cottages in his native county of Wiltshire and the occupants were all people whom he had known since he was a boy. For personal private charity it is probable that Mr Perrett had no equal in Bristol.

“Amongst his many kindly acts was the gift of £500 towards the cost of providing a recreation ground at Knowle and the park will always be associated with him as it is named Perrett’s Park.”

Mr Perrett’s will revealed a fortune amounting to £8,706 16s 7d.

It seems astonishing that Mr. Perrett’s illegitimacy was never ‘outed’. At the time such an origin was something to be hidden, in much the same way as homosexuality had to be until a few years ago. That nothing was revealed in so many newspaper columns devoted to him perhaps confirms the universal respect in which he was held. He was also a determined self-publicist. He was a reactionary who didn’t give a damn what people thought of his views, yet a benefactor who basked in the headlights of the adulation he received in spades from his fellow citizens. It was a life lived on a public platform. What a help a few private recollections would have been in this enterprise. With it all, just out of reach is the shadow which is Mary Ann. If only we had her version too.

I wrote an extended version of the Charles Perrett story. Click the link below to download:

Leave a Comment